“Our numbers show that over 50 percent of his appointments have been female. Also, about 40 percent self-identify as nonwhite. I think that is a huge step in the right direction for California,” she said recently.

The chief justice was often displeased with Brown’s refusal to restore more funding to a court system decimated by deep budget cuts during the first years of his administration. And she quietly pushed for Brown to name a seventh justice to the Supreme Court, a spot left vacant for more than a year after Justice Kathryn M. Werdegar retired. He finally named his senior legal adviser, Joshua Groban, who was confirmed in late December and will participate in oral arguments in January.

His earlier nominees — Goodwin Liu, Mariano-Florentino Cuéllar and Leondra Kruger — were all highly regarded but none had experience on the bench. Nonetheless, Brown’s appointments to the high court earned Cantil-Sakauye’s approval.

“Because the governor has appointed such stellar people to this bench, our disagreements are humorous but pointed. We disagree but kindly with each other,” she said.

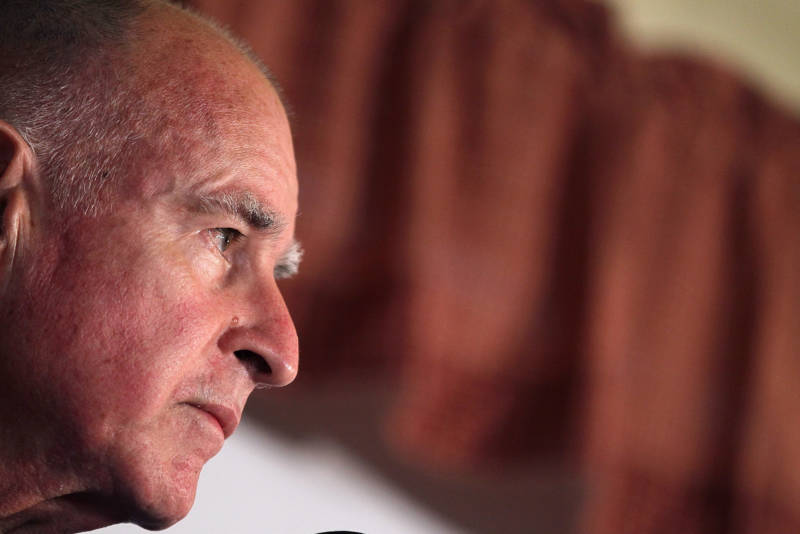

Brown’s imprint on the courts will certainly be felt for decades: Over the course of eight years, he has named more than one-third of all sitting judges in California.

Many of Brown’s judicial appointments, especially to the lower courts, have broken long-standing barriers: the first women ever appointed to the bench in Del Norte, Sierra and Glenn counties; the first African-American woman in San Mateo County; the first Latino men in Butte and Marin counties; and the first Muslim-American judge ever appointed in California.

Something else that distinguishes Brown’s appointees: their professional background.

As San Francisco Public Defender Jeff Adachi noted, being a public defender or defense attorney used to mean forget ever becoming a judge.

“If you were a public defender … it would be actually held against you by these more conservative administrations,” Adachi said.

“It even discouraged generations of lawyers from becoming public defenders” because, he said, they thought having “defense attorney” on their resume would disqualify them from the bench.

There used to be a saying: “Unless you’re a prosecutor, don’t even put your application in,” Adachi said.

That was not the case under Brown, who named dozens of defense attorneys to the court.

Advocates for crime victims say judges with defense backgrounds tend to go lighter on criminals, a notion Adachi disputed.

“There’s a joke that some public defenders become tougher judges because they’re trying to bend over backwards to show that they don’t have a bias in favor of their former clients,” he said.

Both Adachi and Cantil-Sakauye also noted that Brown has appointed much younger attorneys to the bench, people in their 30s and 40s. The chief justice says they have a distinctly different outlook on the law.

“An interest in social justice issues. An interest in homelessness. An interest in climate. An interest in anti-gun. We’re just seeing a whole new generation,” she said.

Cantil-Sakauye, who recently disclosed she had changed her voter registration from Republican to “no party preference,” is thrilled that Brown is making the court better reflect California in the 21st century.

The first time he was governor, Brown used his judicial picks to try to influence issues like capital punishment. But Brown said he no longer expects judges to radically change public policy.

“I have more respect for the slow-moving character of what the court is and what the court has to be,” he said.