And with rent, food, bus fare or car costs, and hundreds of dollars out of pocket every semester for textbooks, she said, students typically need those paychecks.

“I think a lot of times legislators are disconnected from what students actually endure,” she said. “It sounds good, but for a lot of people, especially students of color, it’s unrealistic.”

Youngblood’s skepticism illustrates the complexity of debates about tuition-free college programs, which are springing up around the country at a time of rising discontent with student debt and widespread evidence of food insecurity and homelessness on campus. Some state plans have garnered bipartisan support. But often, say college affordability advocates, “free” doesn’t really mean free.

California’s Promise program, for example, doesn’t address non-tuition costs, which make up the bulk of community college students’ total price of attendance. When those are taken into account, in most regions of the state, low-income students pay a higher net price for community college than they would to attend a California State University campus or University of California campus, according to a recent report from The Institute for College Access and Success.

That’s because there’s more grant aid available at the state’s four-year universities, the report says.

For community college students, “there isn’t nearly enough financial aid to bring their other costs of college in reach,” said TICAS vice president Debbie Cochrane in a statement accompanying the report.

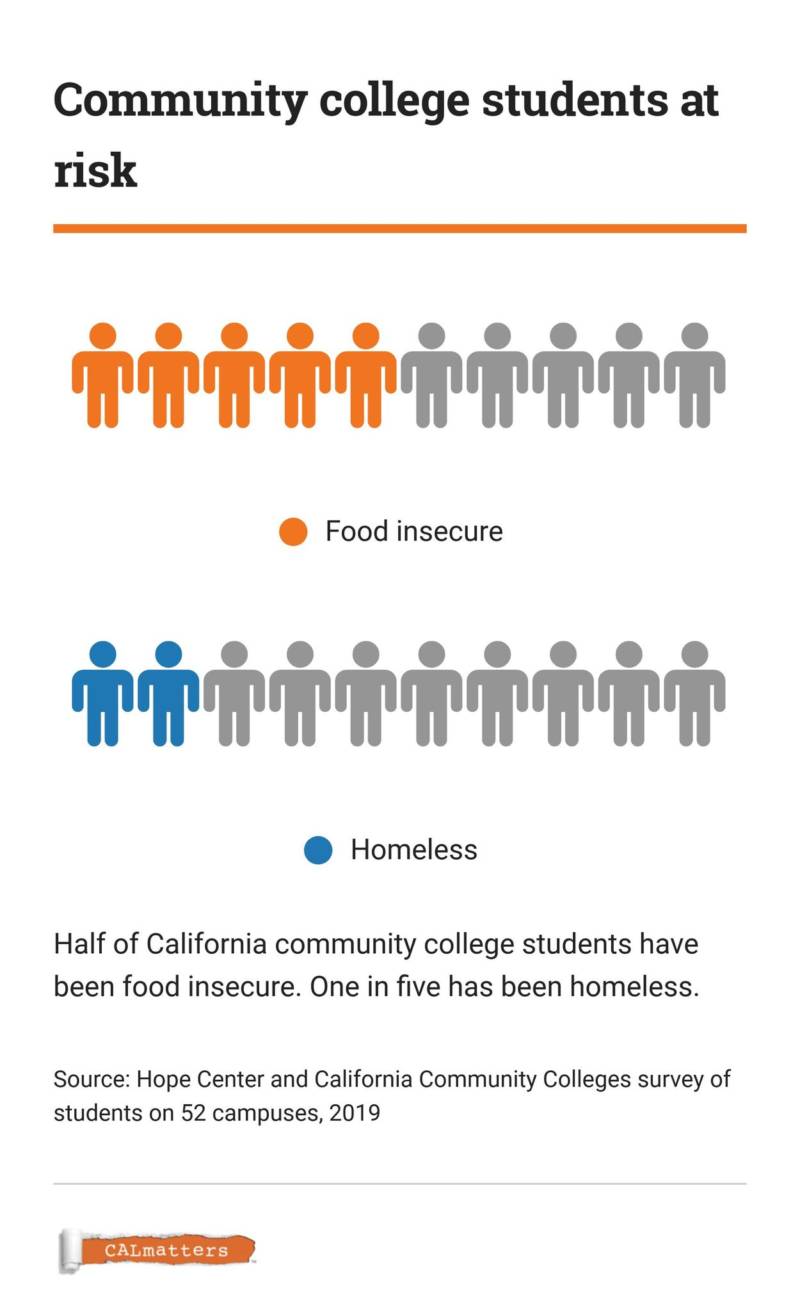

In a recent Hope Center survey of 40,000 California community college students, half reported experiencing food insecurity in the past year; one in five said they’d been homeless.

Assemblymember Miguel Santiago, the bill’s author, says he sees the College Promise program as just one piece of a larger college affordability agenda. The program’s requirement that students apply for other federal or state aid, the Los Angeles Democrat said, is designed to lead them to grants that might help cover their living costs.

Over a third of high school graduates nationwide didn’t complete a federal student aid application in 2018, according to a NerdWallet analysis, leaving $2.6 billion in need-based Pell Grants on the table. Students can be confused by the form, think they’re not eligible for help, or have concerns about family members’ immigration status.

Santiago also said he wants to amend his bill so that current part-time students could receive Promise fee waivers if they decide to take 12 units per semester. But he was firm that students should attend full-time. That way, he said, “it’s not just a giveaway. There’s responsibility on both sides.”

California’s economy will need about a million more college graduates by 2030 than the state is on track to produce, the Public Policy Institute of California estimates. Conscious of that projected gap, policymakers are looking for ways to encourage students to earn degrees quickly.

Lawmakers’ focus on tuition was on display in Gov. Gavin Newsom’s proposed 2019-2020 budget. Community colleges have spent the past year building food pantries and making it easier for students to spend food stamps on campus, thanks to $10 million in grants from a state fund aimed at fighting college hunger.

But that money expires this year, and Newsom didn’t include plans to renew it—though the governor did set aside $40 million to provide a second year tuition-free, along with more support for students with children.

A coalition of anti-hunger activists and student government groups has drafted a letter to legislative leaders asking them for $20 million to combat hunger on community college campuses next year, along with $5 million each for UC and CSU.

“The forward momentum in preventing hunger on college campuses has been tremendous,” reads the draft letter, which the coalition shared with CALmatters. “Without this funding, campus leaders expect to lose momentum and even lose ground.”

Because California already waived community college tuition for low-income students prior to the Promise program—the income ceiling is about $37,000 for a family of four—it mostly helps students whose families earn too much to qualify for a waiver.

That poses a dilemma for people like Chris Nellum, director of higher education research at The Education Trust-West, which works to close the achievement gap for low-income students and students of color.

“It is really challenging to say you don’t support a free college program,” he said. “It’s something I struggle with personally.”

“Is this going to help students? Sure, it’ll help some students. But for the students we care about at Ed Trust West, the ones I’ve spent my career trying to support, I’m not sure it’s going to help them.”

Some community colleges have chosen to use their Promise dollars for non-tuition benefits designed to help the neediest students, rather than slash fees for everyone.

At Mount San Antonio College in the Southern California suburbs, administrators crunched some numbers and found that the typical student who would receive a fee waiver was a white, male teenager from the upper-middle-class town of Diamond Bar.

“The zip codes where they were from and the age group doesn’t match what our neediest students are,” said Bill Scroggins, the college’s president.

Instead, said Scroggins, the college is using the money to offer first-time students free bus passes, book grants of up to $250 per semester, and food cards that can be used to buy meals on campus. To qualify, students must be enrolled full-time and earn at least a 2.0 GPA.

Las Positas College, in the San Francisco Bay Area, has also used part of its Promise funds to help students with textbooks—up to $500 per semester. The college will spend the rest on hiring more financial aid counselors to help students apply for other forms of aid, said vice president of student services William Garcia.

While about half of the college’s students already paid no fees, said Garcia, very few of them had any assistance with textbooks and supplies, which can cost full-time students nearly $2,000 a year.

“If you start the first day of class and don’t have that book the teacher’s requiring, you’re going to get behind from day one,” he said.

Supporters of a universal tuition waiver say its importance is symbolic. It sends high-school students a simple message: College is accessible to you.

The Los Angeles Community College District has seen a 24 percent bump in Los Angeles Unified School District graduates enrolling right after high school since it began offering them a year of free tuition in 2017. Students who participated in the district’s Promise program were also more likely to continue for a second year than their peers in previous classes.

“When we came up with this, we thought, ‘How do we make this a conversation so that college is within somebody’s reach, so they can feel it and taste it, whether they’re a parent or a student?” said Santiago, who also sponsored the original College Promise legislation in 2017.

Universal programs can also be politically popular, as middle-class families, too, are squeezed by college costs. In a PACE/USC Rossier poll released this week, California voters ranked college affordability as the second-most important education issue for the state, behind gun violence in schools.

Some states have gone farther than California, extending tuition-free community college to part-time and returning students. As California lawmakers debate adding a second free year of tuition, they will also consider whether to overhaul the state’s other financial aid program, the Cal Grant, to cover more of students’ living costs.

With a Democratic super-majority in the legislature, the question is likely not to be whether to continue California’s march toward free college, but how far to go.

“The idea is not going anywhere,” Nellum said.

This story and other higher education coverage are being supported by College Futures Foundation.