Gov. Gavin Newsom signed an executive order Wednesday halting executions in California, saying that the death penalty has been a costly failure that is unfairly applied to people of color and the mentally disabled.

Gov. Newsom Halts Executions; Opponents Call Move an Abuse of Power

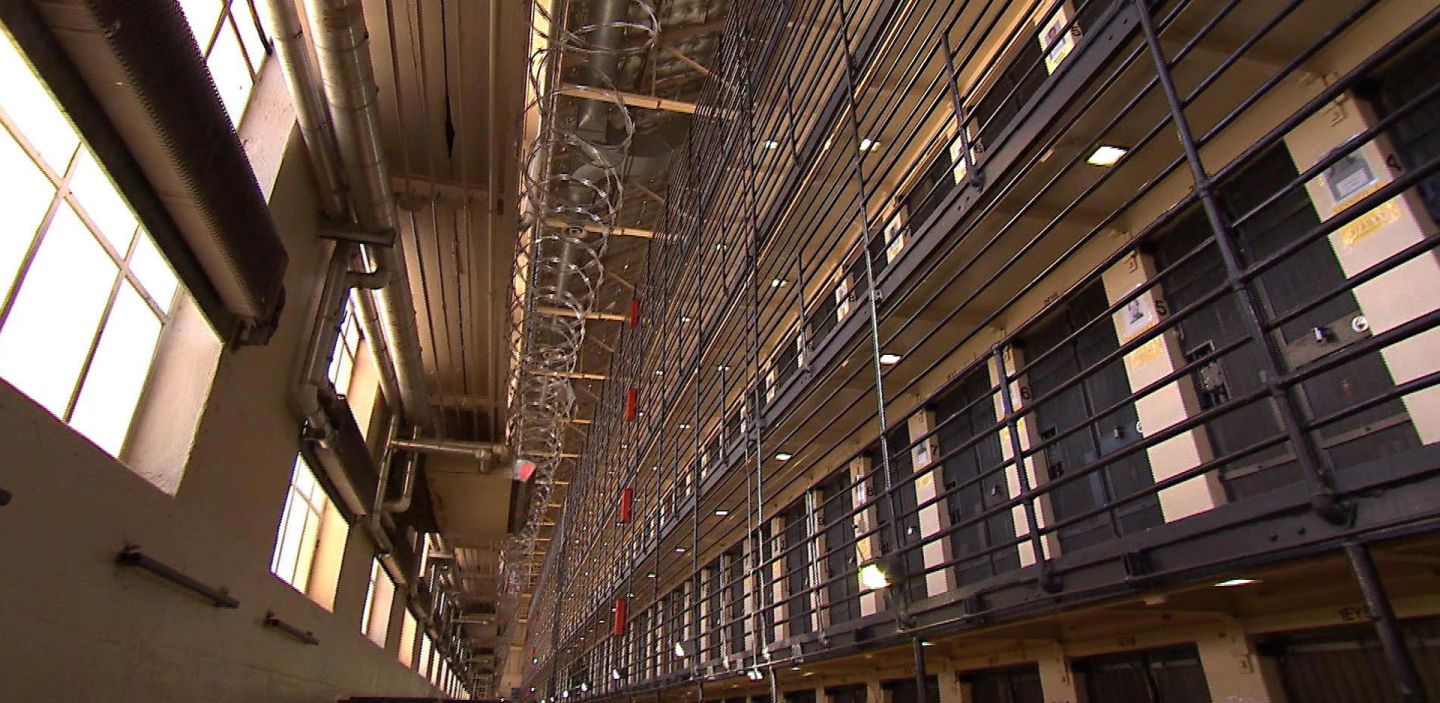

The order grants a reprieve to the 737 inmates on California's death row, a move that seems likely to end the prospect of any executions during Newsom's term, but would allow the next governor to resume capital punishment. He also ordered the closure of the execution chamber at San Quentin State Prison and withdrew the lethal injection protocol — the legal regulatory framework setting out how to put a prisoner to death in California.

California hasn't carried out an execution in 13 years, but is close to resuming them. Twenty-five people on death row have exhausted their appeals, Newsom repeatedly said.

"We are considering executing more people than any other state in modern history — to line up human beings, every day, for executions for two-plus years," he said. "Premeditated, state-sponsored executions. ... I cannot sign off on executing hundreds and hundreds of human beings, knowing among them are people who are innocent."

Newsom struck a personal tone in those public remarks made shortly after he signed the order at the state Capitol. Flanked by Democratic lawmakers and other elected officials, he spoke about a family friend, Pete Pianezzi, who was convicted of murder and narrowly escaped the death penalty after just one juror opposed it. He was eventually pardoned after a mob hit man flipped and admitted that two other men had carried out the killings.

The governor also cited other personal experiences — seeing a man he went to high school with during a tour of death row, and knowing that a former foster brother spent time in San Quentin for crack cocaine dealing. He said those experiences and conversations with victims in recent days — along with the knowledge that the state would be resuming executions soon — led to his decision.

"This has been a 40-year journey for me," he said, noting that he spoke with family members of victims on both sides of the issue. One told him that he had a responsibility to "eradicate evil," she said, while another said that he had no right to take another life in the name of her daughter. He acknowledged that those messages were hard to square.

"To the victims, all I can say is, we owe you and we need to do more and do better, more broadly for victims in this state ... but we cannot advance the death penalty in an effort to try to soften the blow of what happened," Newsom said.

The move was met with scorn from supporters of the death penalty, who called the blanket reprieves an abuse of power and questioned whether Newsom has the legal authority to withdraw the lethal injection protocol, which is set by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation. But Democrats roundly praised the move, and before Newsom even signed the order, a group of two dozen lawmakers announced legislation to put the abolishment of the death penalty before voters in 2020.

Attorney General Xavier Becerra — who would be responsible for defending the governor's order if the state is sued — said Newsom's action "represents a bold, new direction in California’s march toward perfecting our search for justice."

California voters have weighed in on the death penalty as recently as 2016, when they narrowly defeated a ballot measure to abolish capital punishment but approved a competing measure aimed at speeding up the death penalty in California. An execution has not been carried out in the state since January 2006, after a federal judge ruled that the lethal injection protocol at the time — a cocktail of three drugs — could lead to unconstitutional suffering.

It seems likely that someone will challenge Newsom's order in court.

Kent Scheidegger, legal director of the Criminal Justice Legal Foundation — a staunch defender of the death penalty — noted that voters have repeatedly upheld the punishment.

"The use of the reprieve power to block the enforcement of a law that the people have voted on, that he simply disagrees with, is a gross abuse of that power," Scheidegger said. "The constitution gives the governor the reprieve power to use where it's needed in individual cases, where there might be a problem with the case, but it's not the purpose of the power to block enforcement of duly enacted laws."

Republican lawmakers also lambasted the governor. Assemblywoman Melissa Melendez, R-Lake Elsinore, charged that the governor "clearly does not represent the majority of people in this state who want to see justice served for these heinous crimes." And state Sen, Jim Nielsen, a Republican representing Tehama who spent nearly two decades on the state's parole board, called the order "an affront to our system of justice" that betrays both victims and juries.

"The governor has the authority to delay the implementation of the law, but his action is eroding faith of California voters in our democracy and our system of justice," he said.

Newsom responded during his press conference that while voters did uphold the law recently, they also elected him. And he called on the public to repeal the death penalty.

"The people of California have entrusted me ... with the constitutional right to do what I am doing," he said. "I have been crystal-clear about my opposition to the death penalty, I don't think this comes as a surprise. The constitution and the laws of this state afford me the right to do this. The law does not change. It will only change with voters or the Supreme Court."

And progressive Democrats, who run both houses of the Legislature, stood squarely with Newsom.

"Practically speaking, we know that our justice system makes errors. It is a human process and humans make mistakes, especially in groups. But the death penalty is irreversible," Assembly Speaker Anthony Rendon said in a written statement. "We have seen many cases of wrongful convictions reversed only after decades. The most convincing exonerating evidence will not bring back a person who has been executed. The costs of our broken capital punishment system — the financial costs — are also extensive and undeniable."