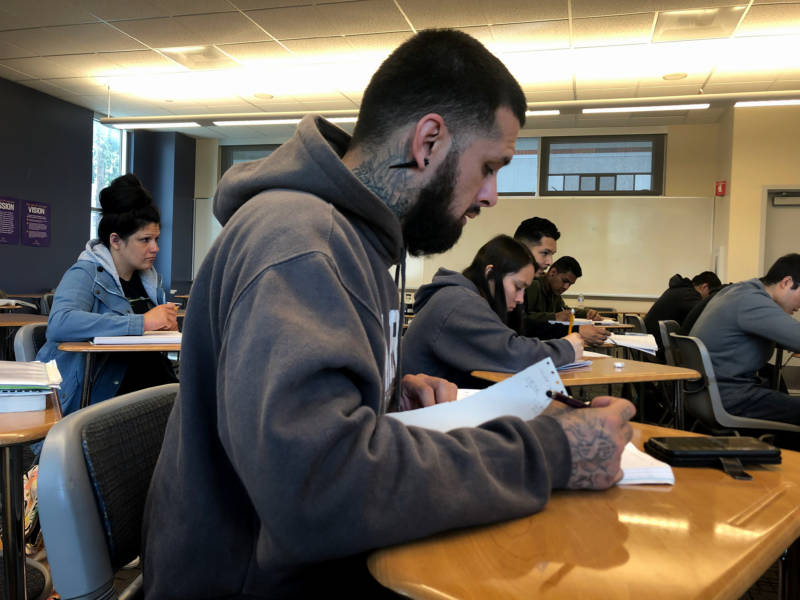

Rey Blanco is running for president — at least if he gets enough signatures from his San Jose City College classmates to get on the ballot for the upcoming student government election.

Is a Big-Ticket Plan to Help California's Community College Students Worth the Cost?

At 36, Blanco is in his first semester of community college, and for the first time in his life he’s embracing school. He’s already vice president and treasurer of the media club and produces a weekly podcast for the college radio station. Plus he’s taking 18 credits, more than a full-time course load, because he wants to transfer to a four-year school as soon as possible.

For Blanco, diving into school is a way to break with a past he’s not proud of, one that led him in and out of jail and prison.

But going full throttle comes at a cost.

To manage his course load and extracurriculars, Blanco had to reduce the number of hours he was working as a barber. So despite his free tuition and financial aid, he still struggles to cover the high cost of living in San Jose, and spent most of this semester couch-surfing or sleeping in his car.

Blanco’s situation is so common state lawmakers recently advanced a bill requiring community colleges to let homeless students sleep in their cars on campus lots. But there’s also a more permanent solution in the works: Community college leaders and their allies in the state Legislature are pushing to create a new financial aid program for their students.

Under the current system, most community college students are shut out of some financial aid programs. As a result, students can end up with higher out-of-pocket costs than they would have at a four-year school.

“The cost of attending our colleges isn’t the cost of tuition,” said California Community Colleges Chancellor Eloy Ortiz Oakley. “It is the cost of transportation, living expenses, books — the cost of not having to work two and three jobs to make ends meet.”

Oakley and other advocates for financial aid reform often fight against misconceptions about who attends community college.

“A lot of folks, when they think about community colleges, the picture that they have in their mind is a student who’s living at home with their parents,” said Debbie Cochrane, vice president of the Institute for College Access and Success. “In fact, all the data show that most community college students are living independently. That means they’re having to pay rent in California markets.”

To address those costs, Oakley has helped champion Senate Bill 291, which would establish the California Community College Student Financial Aid Program for students like Blanco, who are falling through the cracks in the current financial aid system.

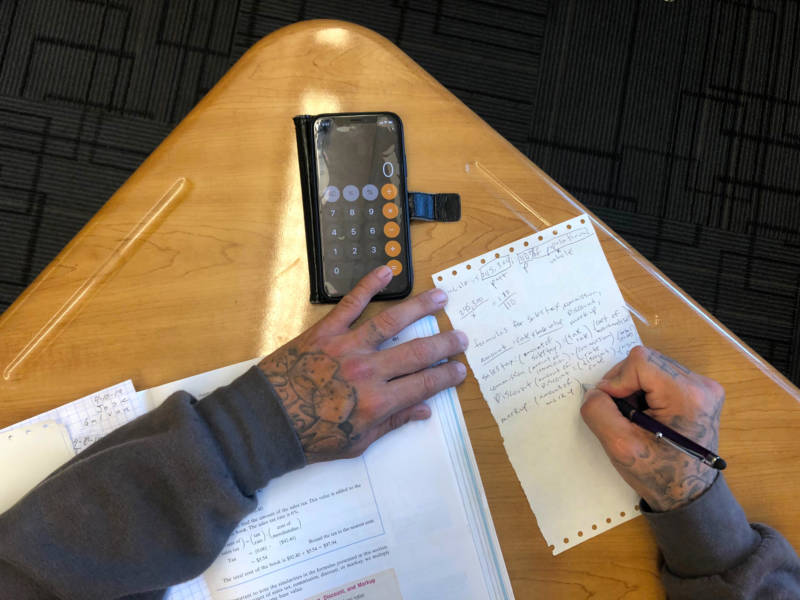

“My biggest problem is I don’t have the time to do tutoring or to focus on my work because I have to try to support myself,” said Blanco, who despite cutting back on his barbershop hours, still spends much of his time outside of class working. “My grades are OK, but I know that if I had that one weekend, or one day of the week to just really focus, then my grades would be so much better.”

Administrators estimate the total annual cost of attendance, including living expenses, is $21,000 for full-time SJCC students who don’t live at home. Meanwhile, the maximum amount of aid a full-time student can receive is roughly $12,000 a year, a shortfall of roughly $9,000, said the school’s financial aid director, Takeo Kubo.

“Students who receive financial aid are typically our lowest-income students,” Kubo said. “They’re living well below poverty level.”

Even so, only about 1% of community college students receive the maximum amount of aid, according to Cochrane of the Institute for College Access and Success.

At SJCC, Kubo estimates most students receive between $4,000 and $5,000 per year in aid.

That’s partly because some state and federal student aid programs are structured to help full-time students, and most community college students attend part time. It’s also because older students like Blanco aren’t eligible for some Cal Grant programs.

Much of the Cal Grant money available is reserved for recent high school graduates, shutting out the majority of community college students.

“A lot of community college students are older,” said Cochrane. “So a lot of them are just left out of the program.”

Fewer than 30 percent of community college students are under 21, whereas 20 percent are, like Blanco, over 35.

Kubo estimates that only about 300 to 400 of SJCC’s 9,000 students receive Cal Grants.

Statewide, the picture is similar. Only about 5 percent of California’s more than 2 million community college students receive any kind of Cal Grant, according to the California Community Colleges. Meanwhile 36 percent of undergraduates in the University of California system receive them, and 32 percent in California State University schools, according to a CSU spokesperson.

“The eligibility rules around Cal Grants just aren’t made well for community college students,” Cochrane said.

From where Kubo sits, the amount of aid available doesn’t come close to meeting students’ needs. “Our students are struggling,” he said. “Given the rent prices here in San Jose — not to mention transportation — if the students want to eat, it really just isn’t enough.”

Blanco gets some aid from the federal Pell Grant program. He even gets a little extra help for textbooks because he’s from an acutely disadvantaged background.

But he still relies heavily on his $192-a-month food stamp allowance, the McDonald’s Dollar Menu and 7-Eleven pizza.

For now he’s able to pay the $700 monthly rent for the room he just found, but the smallest setback could put him in his car again.

Under the California Community College Student Financial Aid Program, which SB 291 aims to create, students would still be expected to contribute some portion of their costs, but the new grants would pick up where the current aid leaves off, providing the lowest income students with an additional $6,000 each year, according to estimates from the chancellor’s office.

The program would have no age requirement, and aid would be proportionate to a students’ course load, so even students attending half time or less could receive some money. Aid would be limited to California residents who show decent academic progress, and would be capped at two full-time years. The program would also be voluntary, so community college districts could opt out.

The legislation has a strong sponsor in state Sen. Connie Leyva, D-Chino, who chairs the Senate’s Education Committee. It’s currently working its way through the legislature.

Proponents argue that making more financial aid available to community college students via SB 291 and other reforms will allow more students to attend full time, and help reduce the high dropout rate.

Today, outcomes are notoriously poor. Fewer than half of students who set out to get a degree or transfer out of a community college do so within six years.

“This proposal would be an amazing benefit to students,” said SJCC’s Kubo. “I think it would really help to increase completion rates.”

“We have wisely invested a tremendous amount of money in paying for the cost of attending college at CSU and the UC,” said CCC Chancellor Oakley. “What we’re saying now is that it’s becoming equally important that we make a similar investment in community college students.”

It’s no small investment. To fully fund the program, the plan’s architects estimate it would cost $1.5 billion a year, with a ramp up in funding over six years, starting with $250 million in 2019-2020.

But Oakley argues there’s more at stake than the future of individual students like Blanco, who hopes to study psychology.

“If we can’t help these individuals complete a higher education or some quality credential that allows them to participate in the workforce, our states and our nation are going to suffer,” he said. “It’s really not just about our students; it’s about the economies of our states and our country.”

This story is part of our series The College Try, about what it takes for students who don’t come from means to get a higher ed degree in California today.