On a recent Tuesday morning, Gettone is up at 5:30 a.m., preparing for the day. This morning I’m following her on her commute. She quickly irons the blazer she’ll wear to work and the shirt her 2-year-old son, Matthew, will wear to day care. When she hears Matthew crying in the bedroom, she goes to scoop him out of bed.

Within a few minutes, Matthew is dressed and ready for school. The toddler is still sleepy and a bit fussy. But Gettone is on a tight schedule and there’s little time to ease Matthew into the day. They need to be out the front door by 6 a.m. Without a car, they face a complex commute, one that involves Uber rides and BART trips. Gettone said it can take up to 2.5 hours.

“Depending on if an Uber is three minutes away or 20 minutes away. It’s like a gamble,” she said.

Today they’re in luck: An Uber is just a couple of minutes away. Gettone grabs her bags and Matthew’s things, including his large, toddler-sized car seat, and heads out the door. From her home in Antioch, she’ll head to Pittsburg to drop her son at a day care she can afford without state subsidies, and then on to Oakland, where she has a job with the city. In the Uber, Matthew vies for her attention.

“Mom … mom … Mom.. mom,” he says repeatedly, as Gettone tries to make small talk with her driver.

Though she works hard to stay positive, this is not how Gettone wants to spend her mornings and evenings. Her commute costs her time with Matthew and her three older children.

“When I come home I’m tired and I’ve missed the whole day,” she said. “Usually I’d be able to come home, cook and talk to them, and ask them how their day was. By the time I get home, everybody’s getting ready for bed.”

But she doesn’t have a lot of options. Gettone has applied for state-subsidized child care for Matthew but has been on the waiting list for over a year. If she got it, the state would cover most — if not all — of her child care costs. It would also free up some of her money for other things, like a car, and possibly allow her to afford a more convenient child care program.

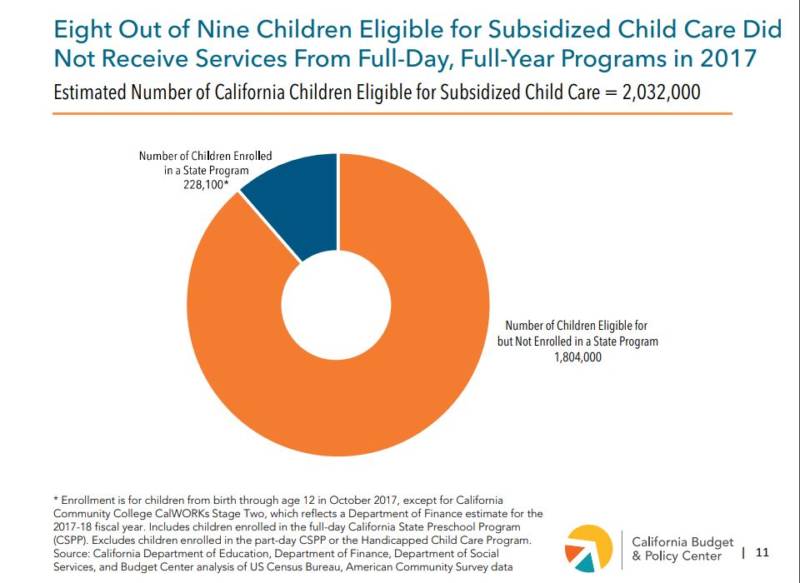

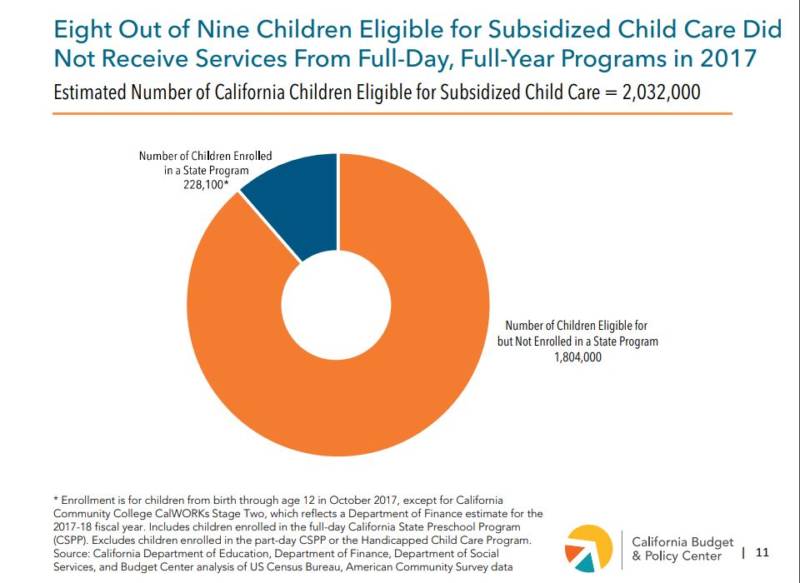

But the number of state-subsidized child care slots is incredibly limited. The California Budget and Policy Center found that of the roughly 2 million kids that qualify for some kind of subsidized care, just 228,100 are actually enrolled in programs that operate on more than a part-time basis. An additional 96,700 kids are enrolled in part-day preschool. A mix of high program demand, high child care costs, a lack of child care facilities and a low-paid workforce combine to make providing enough affordable care difficult.

The lack of affordable care for Matthew has already taken a steep toll on Gettone. When he was born, she was just beginning to run her own hair salon. At first she was optimistic she’d get some help from the state for his child care.

“I figured, you know, maybe some time soon I’ll get a call or something,” she said. “And I even called and stressed to them that I’m at risk for losing my business. They’re like, oh well, call back, just call back.”

Her name never came up. Gettone made too much money while running her salon to qualify for state welfare, which would give her automatic access to care. So after a couple of months of waiting and struggling to maintain her business and pay for child care without help, she made the hard decision to close her shop.

“I had to sacrifice either my dreams or have my son pursue his dreams,” she said. “And my kids’ dreams are more important because I want to see them make it. And that’s what I did. I let go of it.”

She finds herself in a similar position now. She still qualifies for child care subsidies, even though she’s employed with the city of Oakland. And Matthew remains on the waiting list.

The state has made some progress in expanding access to care since it was slashed during the Great Recession. At one point, California cut more than $1 billion in funding. Now, spending has largely been restored to pre-recession levels, about $3.6 billion last year, for child care and preschool. Gettone and other advocates are supportive of Assembly Bill 194, which would allocate an additional $1 billion for state-subsidized care. In his May budget revision, Gov. Gavin Newsom is proposing to spend $80.5 million on additional child care slots. Another $54.2 million would go to CalWORKs stage 1 child care.

Back on her commute, after a short Uber ride from her home to the BART station, Gettone is hurrying to catch her train. Little Matthew has chosen this harried moment to have a meltdown, as 2-year-olds do. So Gettone picks him up while I grab the bulky car seat and we sprint down the stairs to the train. We make it, but as we settle in, I keep thinking: She usually does this alone?

A short ride later and we transfer to another BART that will drop us off in Pittsburg. From there she takes an Uber to drop Matthew at day care and quickly returns to the BART station.

Gettone knows her son is in good hands. The same teacher also looked after her 12-year-old daughter, Margeaux, who has never received subsidized care, even though she’s been on the waiting list since she was a baby.

Gettone would like things to be a bit easier.

“I would like to be closer to my job so I wouldn’t have to commute so far and I would like to have affordable transportation to get there,” she said. “That would alleviate a lot of stress. As well as the funding for child care would help, too. That would help a lot.”

But for now she’s trying to make it work. Back at the BART station, Gettone boards the train for the final leg of her trip. Roughly 40 minutes later, around 8 a.m., the train pulls into downtown Oakland. Gettone steps off, ready to begin her day.