Every morning, sisters Julie Malik and Nell Cox stand at a counter preparing hamburger patties. They are the co-owners of Damburger, a Redding burger joint that their parents bought in 1979.

Malik grabs freshly ground hamburger meat with an ice cream scoop to make meatballs. Down the line, Cox smashes the meatballs in a tortilla press, making 300 patties a day.

The super-thin patty is a Damburger original. It’s so thin, it gets crispy on the edges and it’s never served with a tomato — it’s a signature item that Damburger has been making since the 1930s.

"People come in that haven’t been here for 20 years and they say, ‘It tastes just the same,’ " Cox says.

This simple burger has helped fuel one of the most impactful engineering feats in the state’s history — the Shasta Dam — by nourishing the workers who came to build it. And Damburger would eventually help shape the community of Redding, where many of the workers and their families settled.

'The Best Hamburger By A Dam Site'

Just like during the Gold Rush — where some of the most successful people were those who sold picks and shovels instead of mining for gold — some of the people who profited from the Shasta Dam project never poured concrete or welded a frame.

Instead, they built businesses that sold things the workers wanted. In the case of Damburger, whose restaurant motto is, “The best hamburger by a dam site,” the business grew from sustaining workers as they worked on the Shasta Dam.

Bud Pennington created the Damburger when he came down from Oregon in 1938, the same year construction began. He set up what today we’d call a pop-up shop right next to the place he knew a bunch of hungry guys would be: the hiring hall for the Shasta Dam. People say that he used tree stumps for seats.

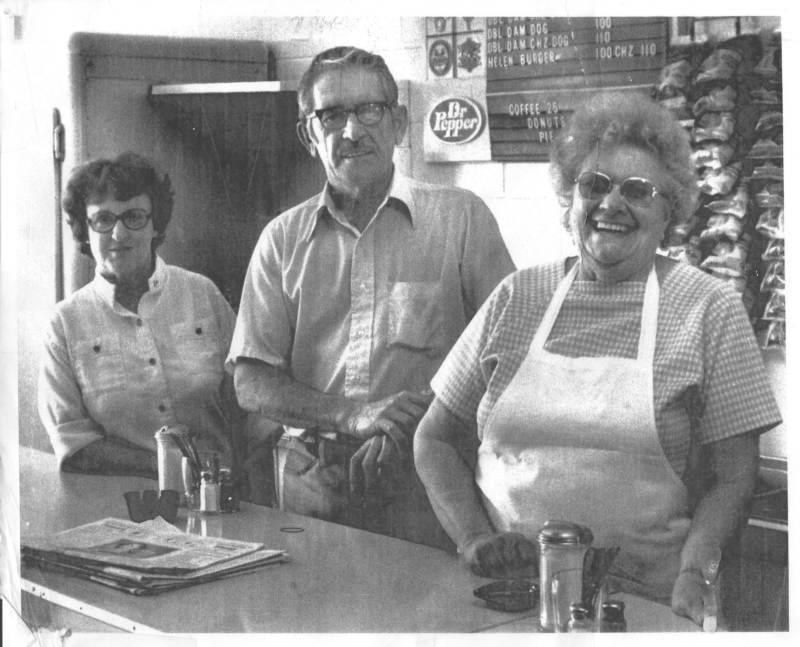

Soon, Damburger got a permanent location. Pennington married Babe, the daughter of his meat supplier, and they hired one employee, a feisty woman named Marge Thayer.

The three of them were characters.

"Lots of jokes, lots of teasing," Cox says. "You could come in and get a good ribbing with your lunch, and maybe enjoy a drink or two with them."

Her sister confirms stories that Pennington was happy to add a little whiskey to customers' coffee. "We have a couple photos and you can see a flask on the counter," she says.

Thayer, who wasn’t great with names, knew customers by their orders.

"'Here comes a double with onions!'" Malik recalls Thayer saying. Or sometimes she’s just call customers "Curly" regardless of their real names.

Thayer worked at the restaurant for 44 years, and it’s rumored that when she died, she was buried in her Damburger T-shirt.

How Shasta Dam Shaped California

Shasta Dam is just 15 miles from the restaurant.

Sheri Harral with the Bureau of Reclamation says it releases 40,000 cubic feet of water per second.

"We call this our Little Niagara Falls," she says.

The dam is taller and wider than the Washington Monument. It was built to prevent flooding and to provide power to Bay Area factories manufacturing planes and ships. The federal government submerged former mining towns, flooded Native American village sites and interrupted the flow of the Sacramento River and its salmon run to build the dam.

Today, water from the Shasta Dam irrigates over a million acres of Central Valley farmland, and its power plant generates enough electricity for every home in Sacramento.

"It’s the major source of water for the Central Valley Project" Harral says. "It goes 500 miles all the way down to Bakersfield."

For good and for bad, California wouldn’t be what it is today without the Shasta Dam. The same could be said about Redding, where Damburger is located. Resorts and marinas line the shores of Lake Shasta.

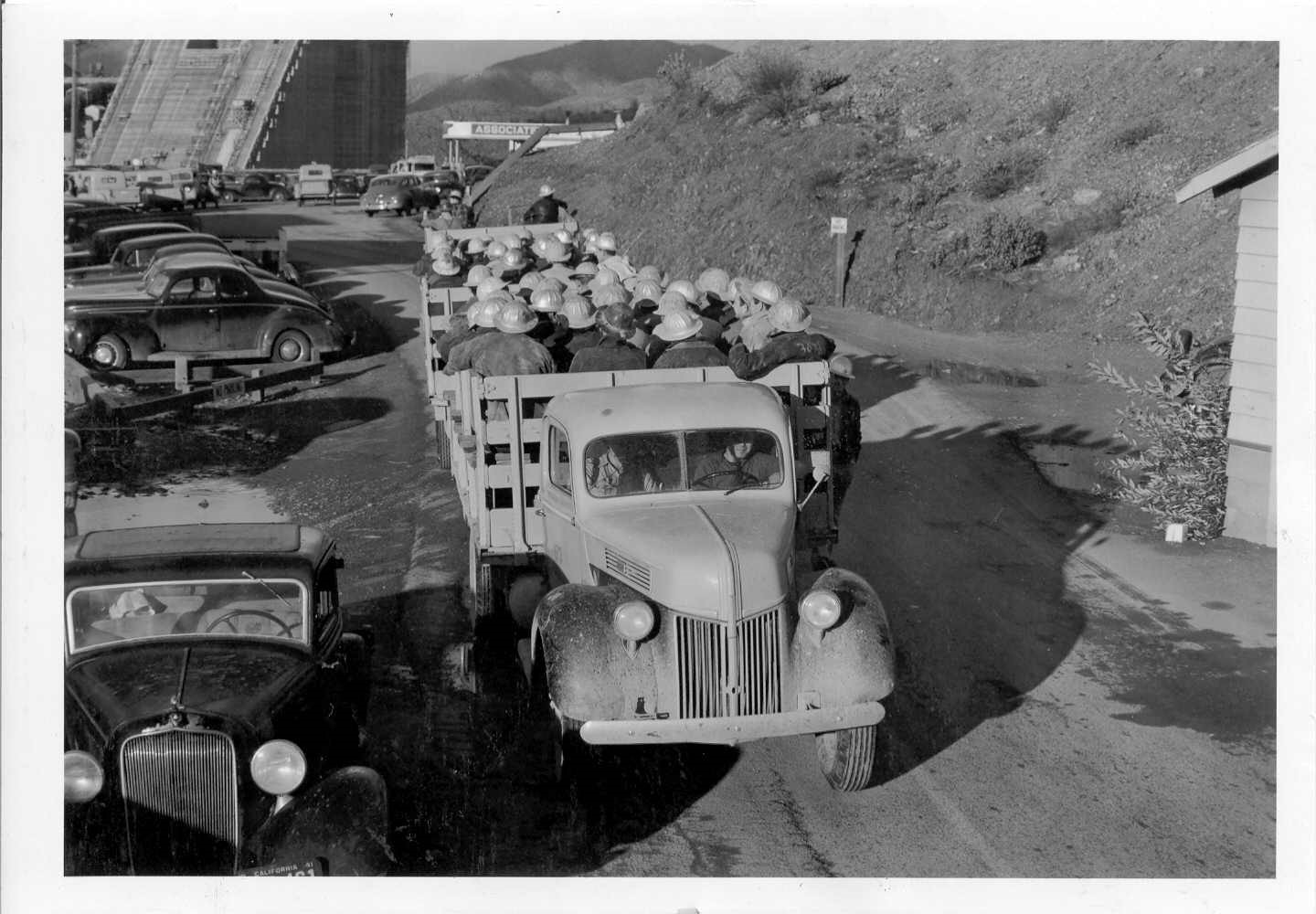

Eighty years ago, the dam’s construction changed the area's population.

Harral says construction on the dam, which went 24 hours a day from 1938 into World War II, began just after the Depression.

“People came from everywhere, once the word got out that there was going to be a dam project here, in hopes of getting one of the 4,700 jobs that this project provided,” she says.

‘Full Circle’ for the Family of One Shasta Dam Worker

One of the people who sought work at the dam was Sharon Thon’s father. Her family lived on a farm about 70 miles away, but moved to the dam site when she was in third grade.

"It just meant security for Daddy and for the family, he was always happy he did it," she says.

He worked as a welder on the project for a year, but the dam would continue to benefit Thon’s family in other ways.

When her parents decided to move back to their farm, they bought a house in a mining town so they could salvage the parts. The town was in the path of the water that would flow from the dam once it was complete, and some of the abandoned houses were going for $50 and the hotel for $100.

"We completely dismantled it," she remembers. "Every weekend we worked on the house, taking down the boards, the lathe, the bricks, the works."

Her family took all of these materials and used them to add onto their farmhouse.

Years later, Sharon Thon married her husband, Iver, and moved to Redding, where they rented a modest home. She was surprised to find out later that it had once been a house provided to a dam worker that had been moved into town.

"We found out they were called 'dam houses,' that it had been moved from the dam," she says. "It’s just crazy to think that we actually moved into a dam house. Another one. It really was a circle."

Loyal Customers Get 'Tags'

The Thons are longtime Damburger customers. Iver Thon guesses they first started dining there back in the 1950s, before you could order french fries or get cheese with your hamburger, when Damburger had only a row of stools, not the handful of tables and patio seating it has today.

When Malik takes the Thons' order, she doesn’t need to ask what they want. They order the same thing every time: a hamburger for him, cheeseburger for her, and fries to share.

The Thons live around the corner from a Carl’s Jr., but they drive 15 minutes to come to Damburger.

"I don’t think we eat hamburgers anyplace else," says Sharon Thon.

Chet Sunde, another regular, admits he comes to Damburger at least three times a week.

"Sometimes five or six," he says. “Obviously, it has a history going back to the dam, but I remember coming here with my dad when I was probably 10, so I’ve been coming here 40 years. It’s just part of the town.”

He just tells Damburger employees that he wants his usual and they know exactly what to make for him: a Double Dam cheeseburger, fries and an iced tea.

Like a lot of regulars, Sunde has a "tag" — meaning his usual order is in a file folder at Damburger.

"It feels good that they recognize who you are. You feel you’re part of the family," says Sunde.

Cox and Malik say those tags are convenient, but they also have a lot of meaning, especially when a longtime customer dies.

"We will lose customers. We’ll have to take their tag out of the box. It’s sad," Nell says, adding that sometimes their family members will come in and get their tag, as a memento.

Malik remembers one longtime customer.

"We actually had a family come in and ask if they could sprinkle some of his ashes in our flower beds because this was his favorite place," she says.

People have held high school reunions at Damburger. One man rented it out for a big anniversary for his wife. Malik and Cox's dad put out a tablecloth and candles, and the cook wore a tuxedo.

Cox says she was just 6 years old when her family bought Damburger.

"We’ve moved homes, but this has always been in my life as far as I can remember," Cox says. "And I think it’s like that for a lot of customers, too. It’s personal."