T

he closest most of us will ever get to the remote oil field site where a Chevron well has been leaking crude petroleum for 2½ months is a fast trip on Interstate 5 on the way from the Bay Area to Los Angeles and back.

If you glance to the right as you head south on I-5 past the Buttonwillow exit -- just a glance, because you're probably going 80, maybe burning gasoline refined from California crude -- you'll see a range of low hills. Somewhere amid those distant ridges is where you'd find the Cymric oil field, the site of Chevron's leaking well.

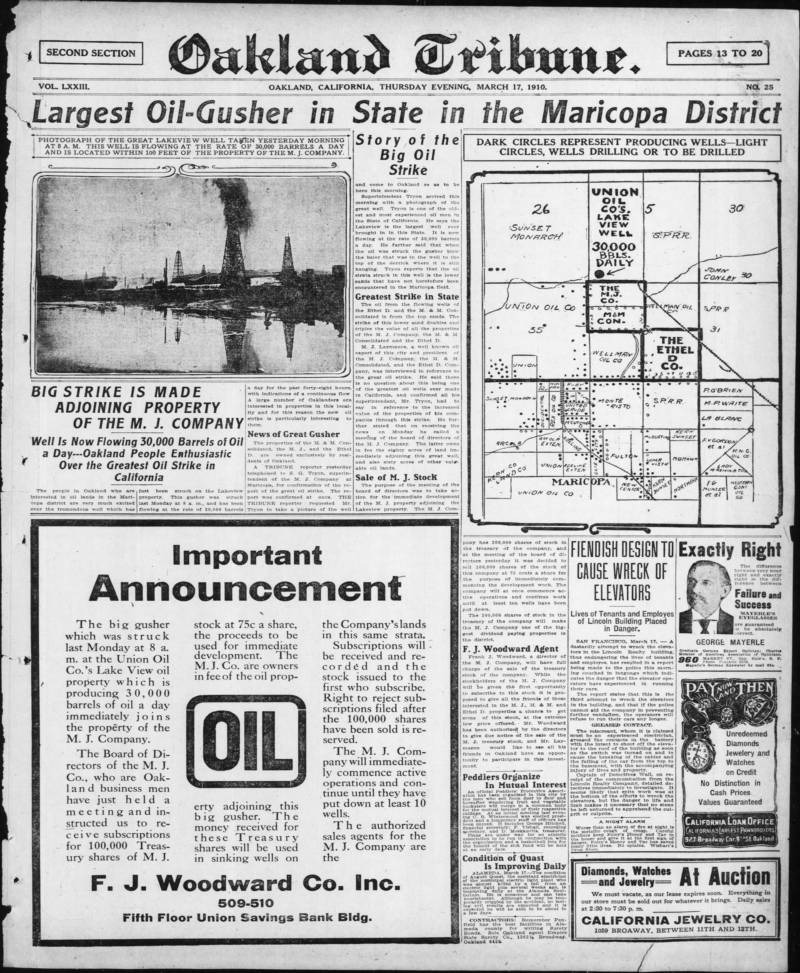

This landscape is not tourist country, but there's a spot 20 miles or so from the Chevron well that's familiar to California petroleum geeks and should be better known generally: the site of the 1910 Lakeview Gusher, an 18-month oil well blowout that was the single biggest crude oil spill in U.S. history.

What happened?

O

n New Year's Day 1909, during a period of intense oil exploration in the belt of hills stretching along the west side of the San Joaquin Valley, a newly organized company began drilling in a promising spot just north of the town of Maricopa, in southwestern Kern County.

For 14 months, no luck. Drillers had gone down more than 2,200 feet on the Lakeview No. 1 well and hadn't seen much to encourage them. By one account, Union Oil Co., which had bought a 51 percent interest in the well after the drilling started, decided it didn't want to sink any more time or money into what looked like a dry hole.

Early the morning of March 14 or 15, 1910 -- yes, there's a disagreement about the date -- before the drilling crew was told of Union's decision, their rig hit a snag deep in the well. A bailer, a long steel cylinder designed to clear rock debris from the hole, was hung up on something. As the crew tried to free it, an explosive rush of high-pressure gas blew the bailer back up the well shaft and shot it into the air with such force it ripped off the top of the oil derrick.

The Lakeview Gusher was underway.

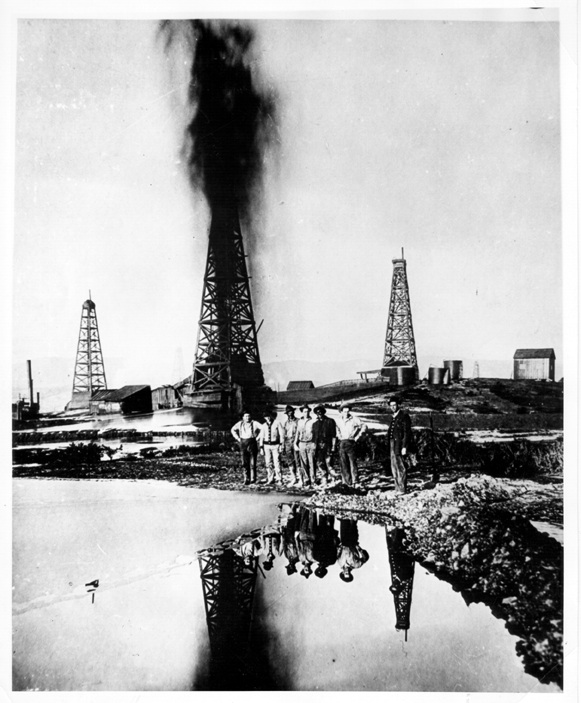

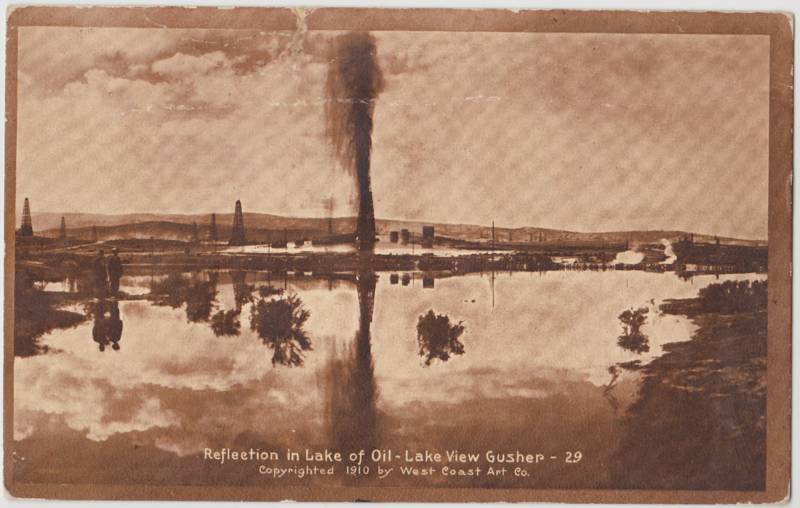

"A roaring column of sand and oil 20 feet in diameter and 200 feet high gushed into the air, and issued a stream of oil at its base, dubbed the 'Trout Stream,' which flowed down every adjacent ditch and gully," writes Bakersfield petroleum geologist Mike Clark in his account of the event.

The Lakeview Gusher wasn't front-page news at first. But as crude oil continued to blast from the hole, it was regarded first as a natural wonder, then as a wild, uncontrollable force, and finally as a headache -- an outpouring so overwhelming that it blackened the countryside for miles around and produced so much oil so fast it created an oversupply that depressed the California oil market.

The biggest problem the Lakeview monster posed, as had other gushers in the California oil fields, was the nearly complete lack of infrastructure to deal with it. Nearby tank capacity was quickly used up and provisions had to be made to ship the oil for processing through the scant pipeline network in the area.

B

ut first, some way had to be found to tame the flow. As streams of crude oil surged across the landscape, some worried it would reach (now vanished) Lake Buena Vista, a body of water on the edge of the valley that was used for irrigation.

Workers built dikes and primitive dams to contain the hundreds of thousands and then millions of barrels of oil that spouted from the well. Soon, the gusher was surrounded by 20 large ponds, or sumps, that slowly filled with black liquid.

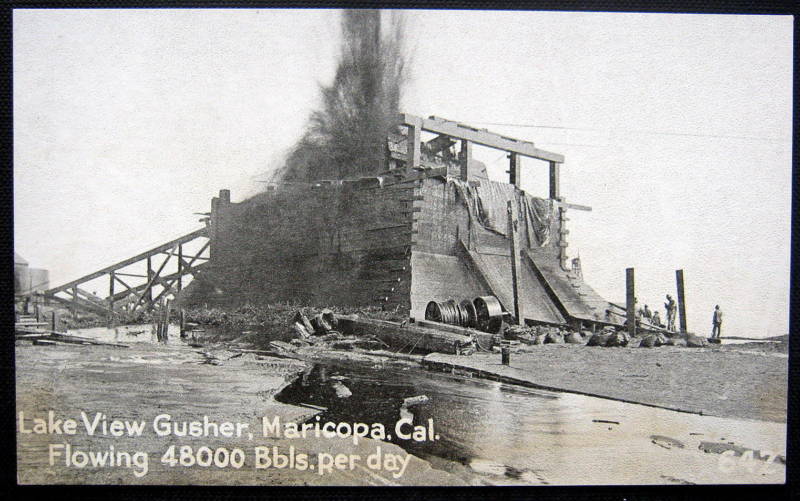

A month after the Lakeview well blew, crews began building an enormous wooden box they hoped would stifle the exuberant outflow. The structure, said to have been crafted from enormous 14-by-14-inch timbers, took about a month to hammer together and tow into place over the gusher. It did nothing to stanch the torrent. Soon the structure began to disintegrate, and it vanished when the ground beneath it collapsed.

By some accounts, the torrent reached a height of 480 feet at times. Newspapers reported it could be seen from downtown Bakersfield, 35 miles to the northeast.

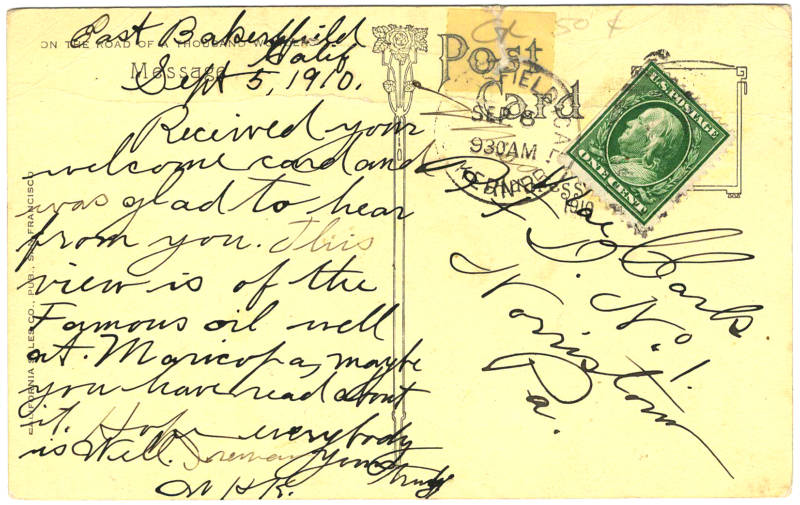

Earlier gushers had come and gone, including some that briefly reached the same astounding rate of flow the Lakeview attained. But no one had seen anything like this -- a hydrocarbon geyser that continued day after day, week after week, month after month. It became a postcard subject and tourist attraction, even though fire and toxic gases posed a constant danger and spectators ran the risk of being drenched in oil if the wind shifted.

E

asily the most vivid account of a visit to the Lakeview Gusher came from W.D. Young, who worked in the Kern County petroleum industry. Writing in a long extinct journal called California Oil World, he described the scene:

"It’s hell, literally hell," Young wrote. "It roars and rips like hell. ... It smells and terrifies like hell. It is as uncontrollable as hell. It is as black and hot as hell."

It took seven months for the hundreds of workers engaged in the battle to rein in the gusher. In a feat of brute labor, they built a 20-foot-high circular sandbag dike around the well. The pool inside the dike was finally deep enough to reduce the gusher to what geologist Mike Clark describes as "a gurgling spout."

That didn't halt the flow. It kept coming until the well caved in, in September 1911.

Estimates of the volume of crude oil produced by the Lakeview gusher are astounding and a little all over the map. A 1920 U.S. Geological Survey report put the daily peak at 65,000 barrels, or 2.7 million gallons. Clark pegs the peak flow at nearly double that -- 125,000 barrels, or 5.25 million gallons, daily.

The 18-month gusher total ranges from 8 million to 9.4 million barrels of oil -- 336 million to 395 million gallons.

A

t first, the gusher was seen as a boon, a windfall of black gold. But as the well continued to spew forth month after month, it began to create a glut on the oil market and caused crude prices to fall by 50 percent.

In late July 1910, relaying reports that the gusher seemed nearly spent, the San Francisco Call said the news was cause for thanksgiving.

"Operators have been earnestly hoping that the Lakeview would be checked," the Call said. "It is today the one demoralizing factor in the industry. It has heaped its enormous output on the market at a time when production and consumption were balanced. It came without warning, when neither physical storage facilities nor financial arrangements had been completed for its care. In itself it has been a source of untold expense."

The glut occurred despite the fact millions of barrels of Lakeview oil never made it to market.

Because the crude was stored in the open air for so long -- and through two blazing summers in the Kern County oil fields — much of it simply evaporated or percolated back into the ground. Estimates of the amount of crude lost this way generally range from 2 million to 6 million barrels.

Despite the Call's hopes, the gusher kept going for another 14 months. Later, Union oil company attempted to tap the well's underground reservoir again. The new well did produce oil — a mere 30 barrels a day — and was soon abandoned.