Frida Kahlo is everywhere. The iconic Mexican artist’s defiant red-painted lips, knowing gaze and proudly worn unibrow framed by serpentine braids can be seen on the front of countless mugs, socks, key rings, mouse pads and pieces of jewelry.

Makers sell these products in stores and on websites like Etsy, where the search term “Frida Kahlo” brings up nearly 20,000 results.

But the Frida Kahlo brand is big business, too. Multinational corporations like Mattel and Converse are also cashing in on the iconic artist, marketing products like the Frida Barbie doll and Frida sneakers, respectively.

And now, some small-scale artisans are finding themselves in a head-to-head fight against those corporations, a confrontation that raises complex questions about ownership of cultural heroes in the digital age.

One of these artists is Cris Melo. The Brazilian-born painter lives in Nice, a small town in Lake County, and has been making whimsical portraits inspired by Frida Kahlo’s image for the past 20 years.

Melo says she isn’t a particularly religious person. But she feels very attached to Kahlo and sometimes even offers up a prayer to her.

“I tell her, I’m not doing this for me. I’m doing this for you,” she says. “So stand with me. Hold my hand. Because it’s scary.”

Melo is timid and elfin, with dark eyes and a wide, expressive mouth. She certainly doesn’t look like the type of person who’d launch legal proceedings against a powerful corporation. Yet she’s suing the company that claims to own the Frida Kahlo brand.

Making an Icon

Though the Mexican government has declared Kahlo’s works part of the country’s national heritage, and people wait in line for hours to see exhibitions of the artist’s work at major museums around the world, she wasn’t at all well-known during her lifetime.

Kahlo spent years living in the shadow of her husband, the monumental Mexican muralist Diego Rivera. It wasn’t until the 1970s, more than 20 years after her death, that Kahlo biographies began to appear, lifting her out of obscurity.

Her paintings started to fetch millions of dollars at auctions. Then, in 2002, came the release of the “Frida” biopic, starring Salma Hayek.

The movie helped amplify the Kahlo brand; it became synonymous with feminine strength in the face of adversity, as well as outsider-underdog power.

“She was a female artist, and Mexican, dark-skinned, disabled and queer,” says Circe Henestrosa, curator of a major Kahlo exhibition traveling to San Francisco’s de Young Museum in March. “Frida’s persona and ethos represents and gives hope and a voice to all these different, diverse groups.”

The Big Business

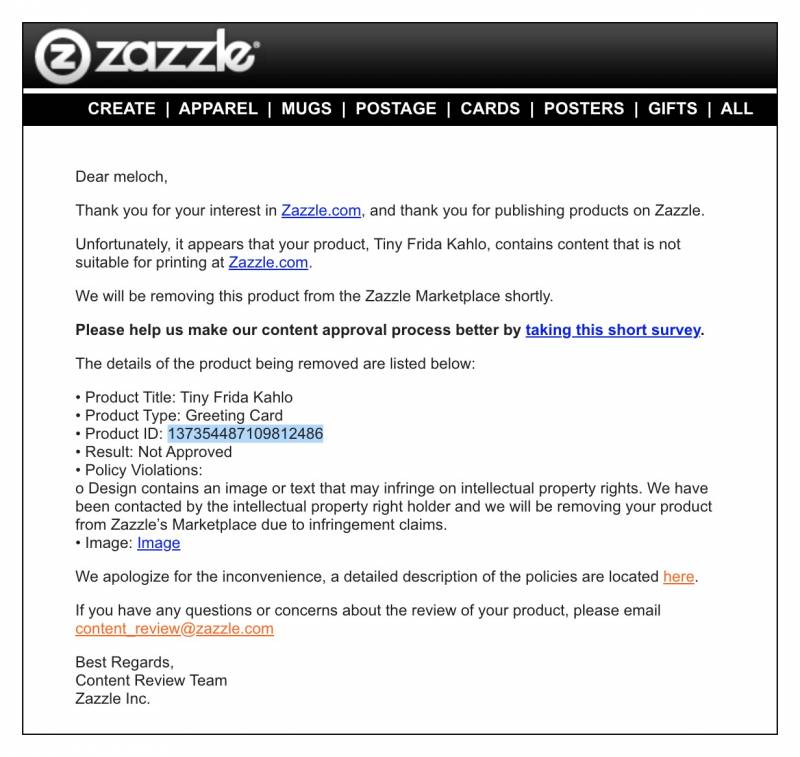

Even before the movie came out, Melo was among the many artists who not only identified with Kahlo, but also found a way to capitalize on all the Fridamania. In 2001, after noticing Kahlo-inspired products on eBay, Melo set up her own online storefront, featuring her Kahlo-like paintings printed on a range of everyday goods, like magnets, T-shirts and tote bags.

“I mean, I would refresh the computer every time and there would be a new bid,” Melo says. “It was amazing. It was so good.”

But then something changed.

Around 2004, Carlos Dorado, a Venezuelan businessman, also saw a big economic opportunity.

Dorado teamed up with the artist’s niece, Isolda Pinedo Kahlo, and eventually her daughter, to launch the Frida Kahlo Corporation (FKC), which registered dozens of Kahlo-related trademarks and set about licensing a pile of merchandise.

FKC’s portfolio includes products like Frida Kahlo tequila, Frida Kahlo makeup, Frida Kahlo Tweezers — an odd choice given the artist’s iconic unibrow — and the aforementioned Barbie doll and Converse sneakers.

“It’s an honor to have a piece of Frida Kahlo that will inspire you day-to-day,” FKC spokeswoman Beatriz Alvarado told NPR in a 2018 interview about the Kahlo Barbie.