Skip to:

- Who was Junípero Serra, and what did he do?

- How statues get officially removed – and what you can do personally

O

n June 19, people around the Bay Area took to the streets to mark Juneteenth: the date in 1865 when the last enslaved people in Texas learned they were free, more than two years after slavery officially ended in the United States. The rallies followed weeks of intense protest across the country over the killings of George Floyd and other Black people by police, and over systemic racism in the United States.

That evening, protesters pulled down a bronze statue that had stood 30 feet high over San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park for more than a century, spattering it with red paint.

The 1907 monument was a tribute to Father Junípero Serra: the 18th century Franciscan priest who presided over the colonizing Spanish mission system in California that resulted in the decimation of the Indigenous population, and who was made a saint by Pope Francis in 2015. Monuments to Ulysses S. Grant and Francis Scott Key, who both enslaved Black people, were also pulled down in the park that night.

The Juneteenth topplings followed the removal of a Christopher Columbus statue in San Francisco’s North Beach neighborhood by city workers ahead of plans by protesters to topple it themselves, and the removal of a Sacramento monument to John Sutter — a 19th century colonizer who enslaved Native Americans at his mill. The day after the Golden Gate Park statues fell, Indigenous activists in downtown Los Angeles watched as a 1932 park monument to Serra was ripped off its pedestal.

And this past July 4, another statue of Serra was torn down in Sacramento’s Capitol Park by protesters following a day of peaceful marches by demonstrators aligned with the Black Lives Matter movement. The same day, Indigenous activists joined forces with Black Lives Matter organizers for a march in Los Angeles, calling for unity and decrying the historical ‘sins’ of the United States.

Black Lives Matter and the Fight Against Serra Monuments

Like the timing of the July 4 marches, the Juneteenth timing of the Golden Gate Park Serra statue toppling was highly symbolic.

“It’s emotional for sure,” says Morning Star Gali about how it feels to see statues come down. A member of the Ajumawi band of the Pit River Tribe — and the project director of the organization Restoring Justice for Indigenous Peoples — Gali has been involved in campaigns for the removal of several statues in the state.

She campaigned against the Sacramento monument to Sutter, and was there to watch it fall. She was present too at the contentious removal of the Early Days statue in San Francisco in 2018, which she and others had worked to remove from public view on account of its portrayal of Native Americans.

America’s current movement toward social justice, and the deep reckoning with U.S. history that it demands, is “absolutely intersectional,” says Gali.

“There is absolutely a mutual understanding of Black and brown and Indigenous liberation that we understand, and we’ve done a lot of work in the past year to get to the point where we’re at.”

She and her fellow Indigenous activists are active partners with the Anti Police-Terror Project — work that’s seen them hold memorials and vigils to honor Black victims of police brutality. In Sacramento, Gali’s efforts to “de-Serra” the city were purposefully held in partnership with the Anti Police-Terror Project, to “really show the solidarity that we have with one another.”

These statues are, Gali emphasizes, “monuments to racism. These are monuments to genocide. And it’s time for them to come down.”

Author and academic Greg Sarris is the chairman of the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, and lecturer at Sonoma State University’s Native American Studies program. In support of “everyone who is suffering the legacy of racism and injustice,” Sarris says that he and his tribe fully stand behind the Black Lives Matter movement.

“Let us not forget that the Indians on this continent were the first to find out what European insensitivity would do to us,” he says. “And do to others.”

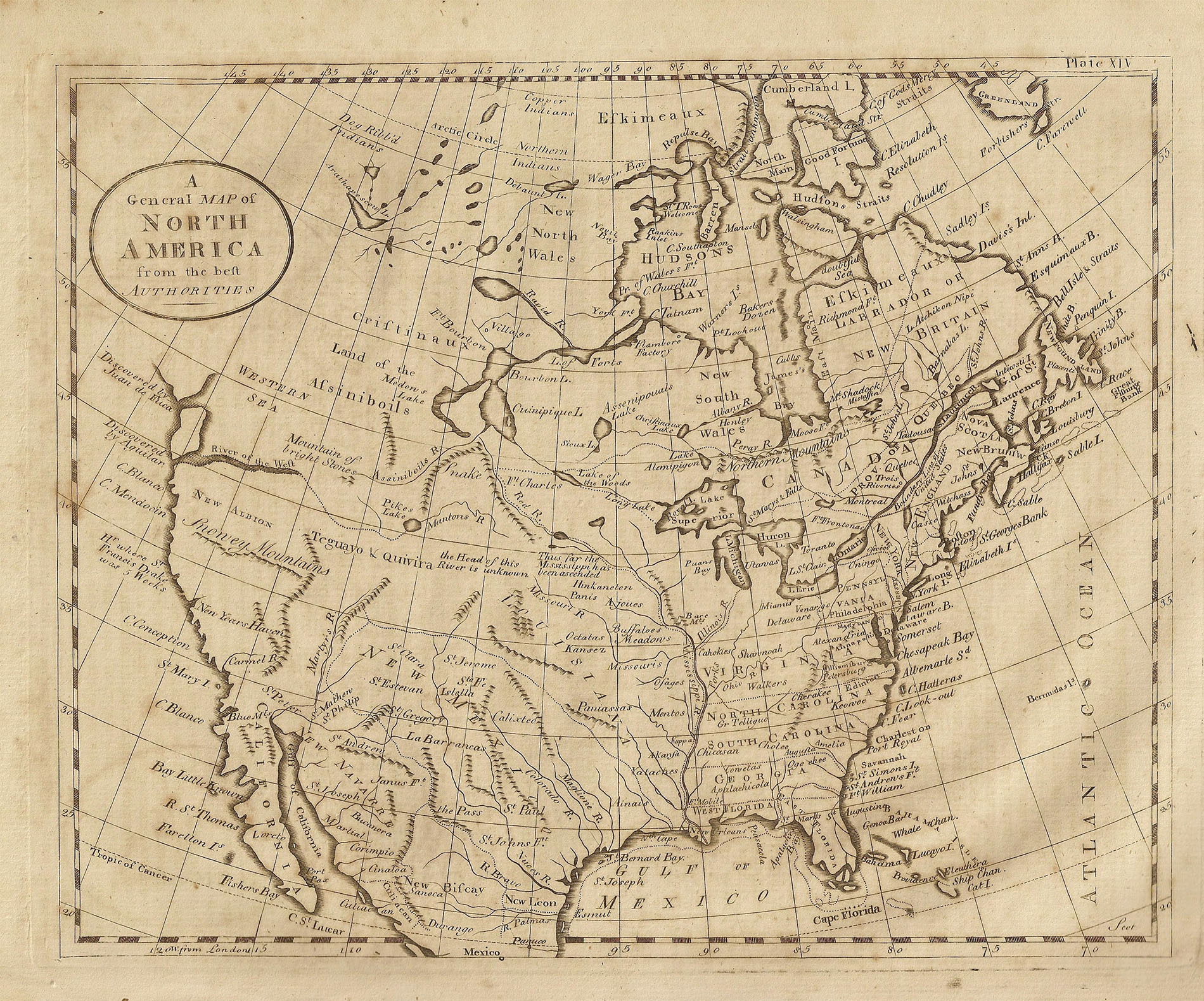

As statues of colonizers are brought down around California — mirroring actions against Confederate monuments further east — Serra remains a particular focus. And for years, he’s been a reviled figure among many Indigenous people for his leadership over a system that resulted in the incalculable loss of Native lives, and forever altered the Indigenous way of life in California.

When it comes to Serra, this is a fight that has been sustained by Indigenous activists for decades. And far from being a matter that relates mainly to California’s history, it says everything about our state’s present — and future.

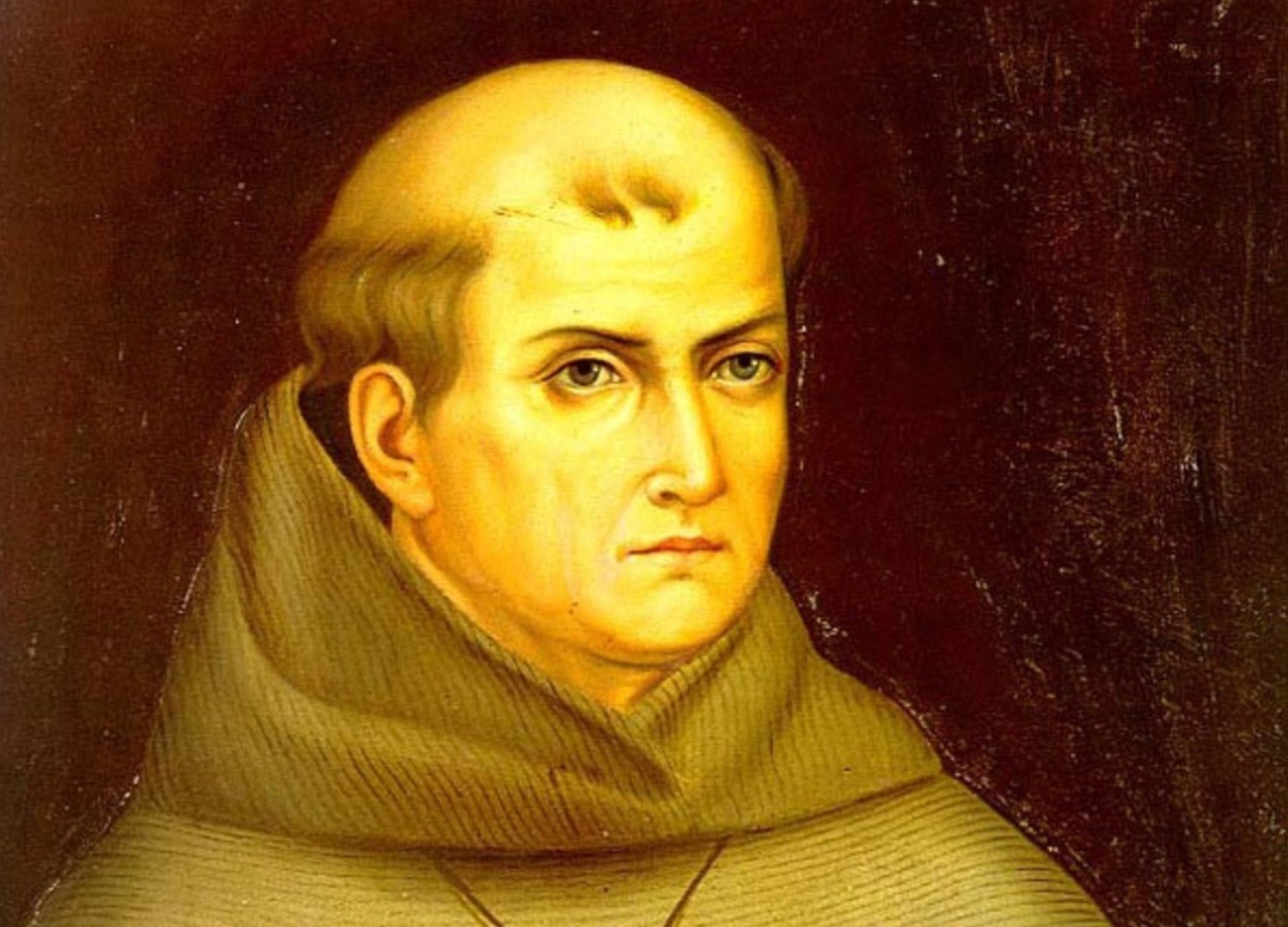

Who Was Junípero Serra?

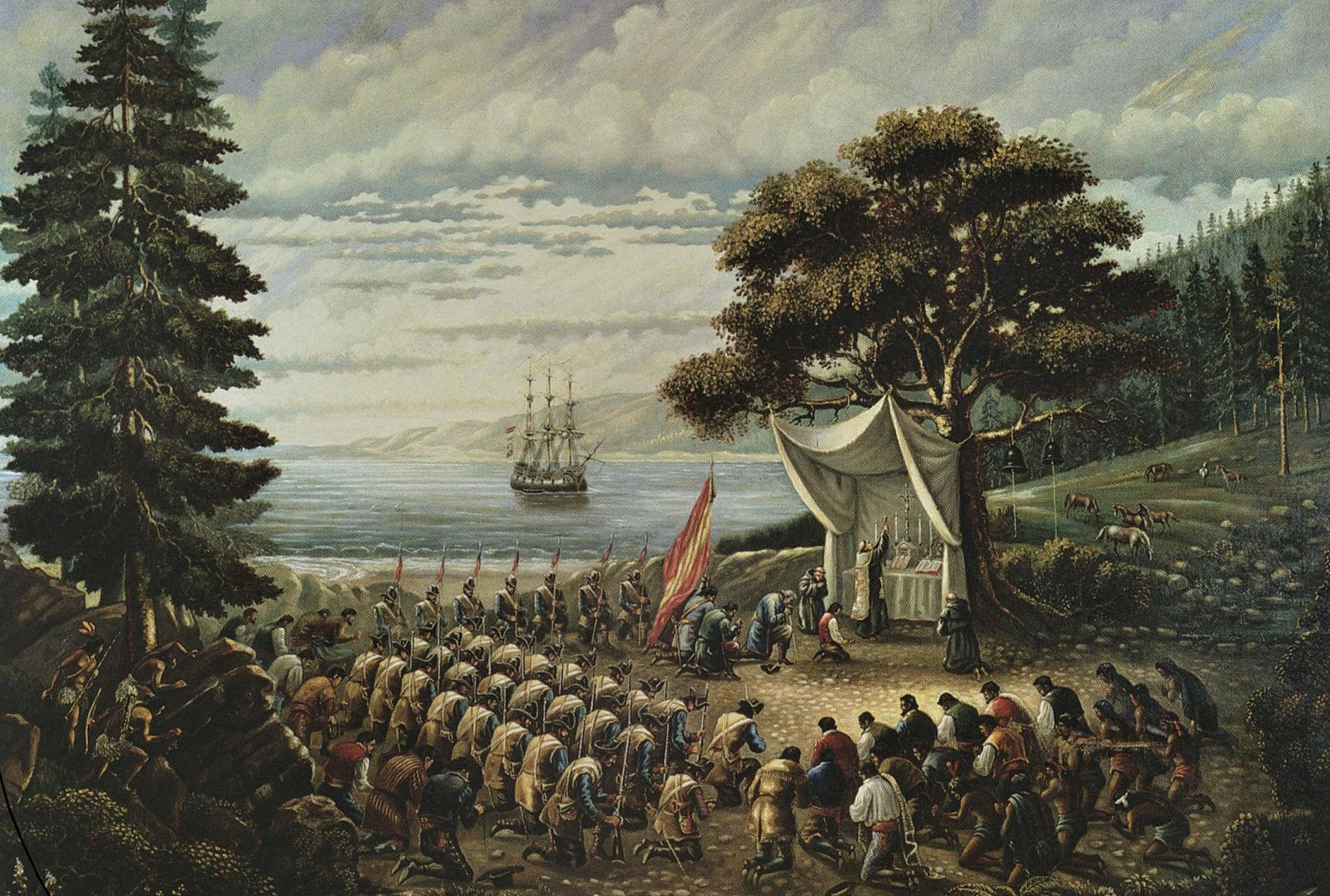

Born in Spain, Junípero Serra first traveled to the Americas in 1749 while in his thirties, to work as a Catholic missionary in Mexico. In 1768, he traveled north to California, and founded a string of missions stretching from San Diego to San Francisco.

If members of a nearby Indigenous tribe were baptized, they were then brought into a mission where they were ordered to abandon many aspects of their culture and customs, and forced into labor — and prevented from leaving. Anyone who tried to escape the mission was subject to being hunted down and brought back.

The Native people in Serra’s missions were subjected to physical punishments like whippings and beating, which Serra himself justified in 1780, writing “that spiritual fathers should punish their sons, the Indians, with blows appears to be as old as the conquest of [the Americas]; so general in fact that the saints do not seem to be any exception to the rule.”

Thousands of Indigenous people in the missions died from exposure to European diseases and from the brutal labor they were forced to perform. It was the discovery of the missions’ birth and death rolls — and the revelation that more Native people died under Serra’s system than were born — that sparked a more widespread re-evaluation of his legacy in the 20th century.

The hard physical labor performed by Indigenous people in Serra’s missions was, for years, characterized in history books as ‘work.’ The word for it used today by many, including the descendants of those people, is ‘slavery.’

“Here we were enslaved in the missions, and whipped and beaten,” says Greg Sarris. “Up to 90% of the population [was] decimated, from which we never really recovered.”

The missions “were concentration camps,” said Corine Fairbanks of the American Indian Movement Southern California in 2015, ahead of a protest at Serra’s canonization at the Carmel mission. “They were places of death.”

Centuries of spiritual and cultural heritage were erased by the Spanish conversion system.

“Serra did not just bring us Christianity,” said academic Deborah Miranda, a member of the Ohlone Costanoan Esselen Nation and author of “Bad Indians”, in 2015. “He imposed it, giving us no choice in the matter. He did incalculable damage to a whole culture.”

Serra the Saint

In 2015, Pope Francis announced his decision to make Junípero Serra a saint. The news was met with outrage in California, with protests taking place in San Francisco’s Mission Dolores, Mission Carmel and Mission San Juan Bautista.

An Indigenous-authored petition urging the pope to reconsider the canonization received over 11,000 signatures, stating that “it is imperative he is enlightened to understand that Father Serra was responsible for the deception, exploitation, oppression, enslavement and genocide of thousands of Indigenous Californians, ultimately resulting in the largest ethnic cleansing in North America.”

A week after the canonization, a statue of Serra in Monterey was decapitated. Two years later in Santa Barbara, another Serra monument at the city’s mission was also decapitated and covered with red paint.

This wasn’t the first time the Church had attempted to elevate Serra’s holy stature. Almost three decades earlier, in 1988, Francis’ predecessor Pope John Paul II had actually kicked off the sanctification process by beatifying Serra. That announcement too was greeted with horror by Indigenous voices, but even back then, it represented only the latest articulation of of anti-Serra protest.

Some saw the canonization as a Catholic matter for Catholic people.

In a 1989 episode of the TV talk show “Firing Line,” host William F. Buckley Jr. suggests to guest Edward Castillo – a Cahuilla-Luiseño professor of Native American studies at Sonoma State University and a Serra critic who participated in the 1969 occupation of Alcatraz Island — that as as a non-Christian, “it’s none of your business who the church canonizes.”

In 2015, L.A. Native activist Norma Flores – who worked with the Kizh Nation/Gabrieleño Band of Mission Indians to author the anti-canonization petition — disagreed. “Junípero Serra is being canonized for being an evangelist of the Native peoples in California,” she said. “Why do we not have an active say in this?”

What Replaces Serra?

Amid a national reckoning with U.S. history, how California deals with Serra is fundamental — not just to the state’s view of its past, but also to how it imagines its future, and the stories it wishes to tell.

“Most people that are crying about these statues being removed cannot name the local tribe of where they live,” says Gali. “The fact that they can’t name that San Francisco is Ramaytush Ohlone territory just goes to show the lack of education, really.” She attributes this lack of understanding to an active “suppression of information about the local tribes.”

So if a statue comes down, or a place is renamed, what is the way forward? Should a statue of Serra be replaced by a figure from local Indigenous history?

It’s not that simple, says April McGill, director of community partnerships and projects at the California Consortium for Urban Indian Health, and the executive director of the American Indian Cultural Center in San Francisco.

An American Indian of Yuki, Wappo, Little Lake Pomo and Wailaki descent, McGill stresses that statues of colonizers like Serra coming down is the start, not the solution. Especially when a city doesn’t work to involve Indigenous people in that removal process, and in what comes next.

When the city of San Francisco removed its Christopher Columbus statue, for example, McGill saw a lack of “Native presence there to follow a protocol” for marking the event. “There’s always somebody speaking for our people,” she notes.

When it comes to the ‘what next’ after a statue comes down, McGill cautions against thinking only in terms of replacing the monuments. After all, statues commemorating individuals are “a white thing,” she says, referencing recent words by Jonathan Cordero, chairperson of the Ramaytush Ohlone.

As to recompense and restitution for the damage done to a region’s Native peoples down the centuries, McGill says a city can begin to truly do right by its Native peoples by recognizing them as living communities with needs.

“I honestly say: give them a space,” she says. “Give them a park. Create a dance arena. Give them back their shellmounds … a place to continue to hold their ceremonies, and grow their indigenous food.” And federal land like San Francisco’s Presidio, McGill says, should be given to “the original stewards of that land,” the Ohlone people.

“That’s how you honor them — not via a statue.”

Ultimately, McGill says, it’s about answering the question, ‘How do we heal?’

Serra in Schools

If you grew up in California in the last few decades, you could be forgiven for being confused about why statues in Junípero Serra’s honor are being pulled down.

Generations of California-educated people chiefly remember their fourth-grade “build a model mission” projects — and a conspicuous lack of criticism around Serra and his actions.