Chanthon Bun, a Cambodian refugee, was released from San Quentin State Prison Wednesday to two unexpected discoveries: he was not turned over to immigration officials for deportation, as he had feared, but he was infected with COVID-19, along with more than 1,000 others at San Quentin.

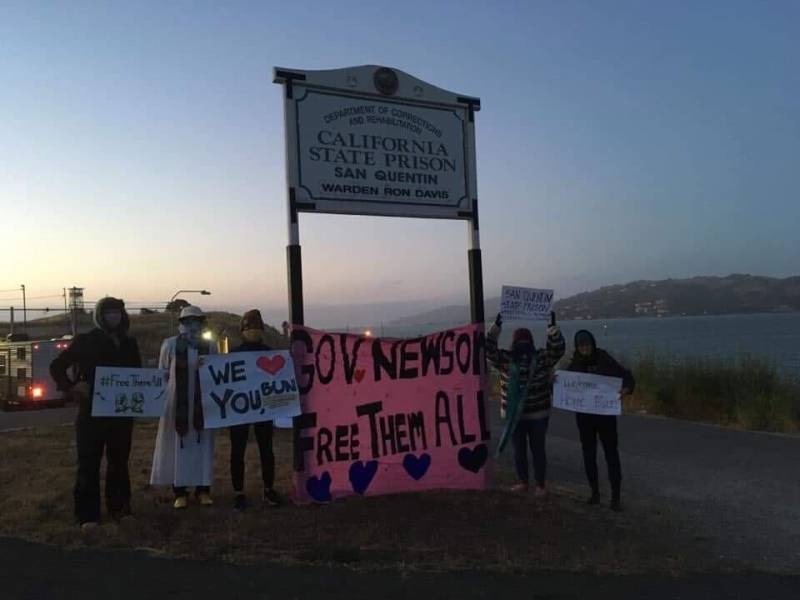

Bun, 41, was greeted at the prison gates in Marin County by friends and supporters who helped secure his release. According to Bun’s lawyer, Anoop Prasad with San Francisco’s Asian Law Caucus Bun served 23 years for an armed robbery committed when he was 18. Friends took Bun to get a coronavirus test, since the disease has swept through San Quentin in recent weeks, and Bun tested positive. By Wednesday night, he had spiked a fever, Prasad said.

Many expected Bun to be handed into the custody of U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), but he was allowed to walk free. An ICE agent had visited Bun last Friday and told him he would be picked up when prison officials processed him for release, according to Prasad. Bun is a lawful permanent resident of the U.S. but because he has a felony conviction, ICE is able to place him in deportation proceedings.

“It’s a miracle that I got released and it’s a blessing,” said Bun Thursday speaking by phone from a residence attached to a Bay Area church, where he is self-quarantining. “Pandemic or not, I’d rather be released out here than to be handed over to ICE,” he said. Testing positive for COVID-19, Bun knew his situation would have gotten worse had he been transferred to ICE.

As a small child, Bun and his family fled Cambodia during the Khmer Rouge genocide of the 1970s, made it to a Thai refugee camp and were eventually resettled by the U.S. government in Los Angeles. Growing up in a traumatized community with no mental health care, Bun, like other young refugees, wound up abusing alcohol and joining a gang, as he described in a recent episode of the KALW Radio series “Uncuffed.”