Four anti-police violence activists filed suit against San Francisco on Wednesday, accusing the city's Police Department of illegally conducting mass surveillance on protesters during a string of Black Lives Matter demonstrations that began in late spring.

SF Police Used Camera Network to Illegally ‘Spy on Protesters,’ New Lawsuit Alleges

In the weeks following the May 25 killing of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police, hundreds of thousands of people in the Bay Area took to city streets to march against police brutality. Despite the mostly peaceful demonstrations that took place in downtown San Francisco, there were also multiple incidents of vandalism, theft and clashes between protesters and police that occurred over consecutive nights, prompting officials to order citywide curfews.

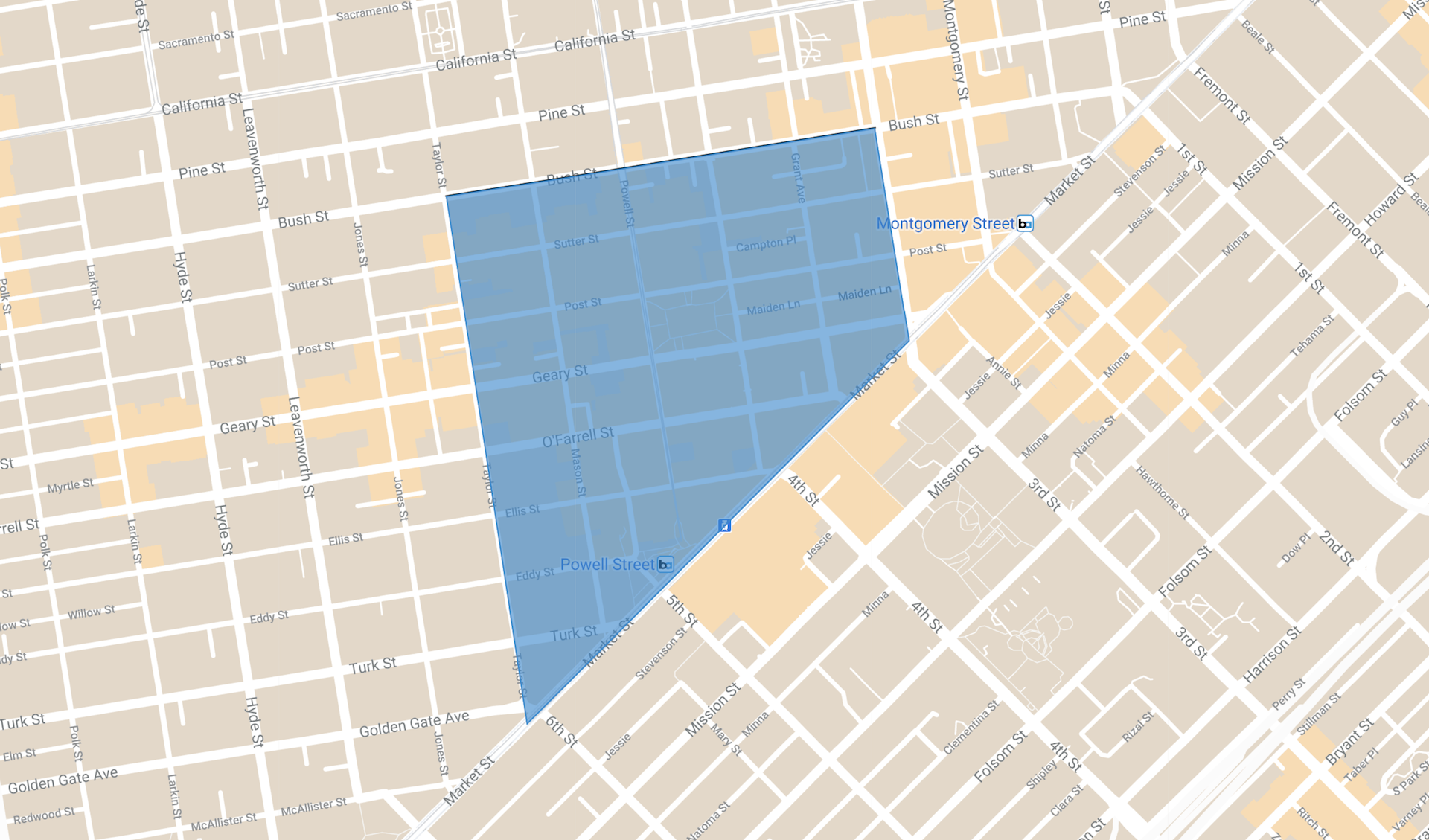

The San Francisco Police Department responded to these protests in part by commandeering private security cameras to keep an eye, in real-time, on a 27-block area surrounding Union Square, according to a lawsuit filed Wednesday that seeks to prevent police from doing so again.

“From May 31 through June 7, 2020, The San Francisco Police Department (“SFPD”) acquired, borrowed, and used a private network of more than 400 surveillance cameras to spy on protesters in real time,” the suit alleges in papers filed in San Francisco Superior Court.

Doing so violated a recently enacted city ordinance that requires the Board of Supervisors to approve any new surveillance systems for police use, according to attorneys with the Electronic Frontier Foundation and the Northern California chapter of the ACLU, who are representing the four activist plaintiffs.

“They reached out to the Union Square Business Improvement District (USBID) and said, ‘We want access to your cameras,’ ” said Saira Hussain, an attorney with EFF. The organization obtained email exchanges through a public records request that confirmed the arrangement.

San Francisco enacted the Acquisition of Surveillance Technology Ordinance in 2019 to specifically prevent police abuse of power, Hussain said. She called the arrangement between the USBID and SFPD “a back door deal.”

“It really is about SFPD playing fast and loose with a city ordinance that is supposed to put a democratic check on how law enforcement is using surveillance technology.”

Police routinely requested and received live access to USBID's camera network in 2019, seeking live surveillance of July Fourth, Pride and Super Bowl celebrations, all reportedly without board approval, according an investigation by the San Francisco Examiner.

SFPD has said officers didn’t always end up using the video feeds they sought to access during those events, but emails obtained through public records requests indicate officers did access live feeds, according to the Examiner.

Hope Williams, a San Francisco resident and lead plaintiff in the lawsuit, organized and participated in a June 2 protest that began at City Hall and culminated in a sit-in in front of the Hall of Justice, in defiance of an 8 p.m. curfew that Mayor London Breed ordered for five nights in early June.

“I was out there to protest police violence against Black people,” Williams said. “We're saying that Black lives matter and how did the police respond but with more abuse of power. It was a tactic to provoke fear and to prevent people from speaking out.”

Other plaintiffs in the case participated in a June 3 protest organized by students at Mission High School and another on June 5 that began at City Hall and headed west up Market Street toward the Castro District.

San Francisco Police Chief William Scott argued in a Aug. 5 letter to supervisors that protests involving “looting, vandalism and rioting” on May 30 created an emergency that allowed police to access cameras without board approval.

Scott followed up in response to questions from Supervisor Aaron Peskin with a Sept. 9 letter. He wrote that although SFPD's Homeland Security Unit requested access to the camera system on May 31, criminal activity did not continue in the Union Square area, so "HSU did not monitor any activities, including first amendment activities." Officers separately reviewed the network's recorded footage network from May 30, Scott wrote, and that resulted in at least one arrest.

The City Attorney's Office provided copies of Scott's letters to supervisors in response to a request for comment on the lawsuit.

On its website, USBID describes itself as “a defined area wherein property owners are self-assessed to fund services that improve the overall quality of life for residents and visitors.”

The business district also touts an elaborate surveillance system to protect members from crime. Nearly 400 cameras cover the 27-block area, bordered by Bush Street to the north, Kearny Street to the east, Market Street to the south and Taylor Street to the west.

“Union Square partnered with law enforcement and became the first area in San Francisco to deploy surveillance cameras (now over 350), resulting in crime enforcement and prosecution,” the district's business plan states. “Footage of incidents may be given to SFPD for investigative purposes. Members of the general public may request video camera footage if not part of an active investigation.”

The USBID cameras can zoom in and focus on a subject, EFF attorney Hussain said, although it’s not clear whether SFPD used this capacity.

“When you consider what people were speaking out against, it just makes this surveillance even more invasive,” Hussain said, “and makes it more likely in the future that people will be afraid to participate or organize protests.”

Shannon Lin of KQED News contributed to this report.