According to Jessica Levinson, Loyola Law School professor and host of the podcast “Casting Judgement”, the election laws are a bit murky, but the answer largely depends on when the incident occurs.

The members of the Electoral College meet to cast their votes for president on December 14, 2020. Generally the party that won the popular vote in a state gets to pick that state’s electors. But, if the winning candidate dies before the members meet, Levinson said the candidate’s political party would choose a new nominee.

“Either the Democratic National Committee or the Republican National Committee have procedures in place and they would pick a new nominee. And then, the idea is that the members of the Electoral College — because they are party loyalists — would vote for that (nominee),” Levinson said.

But even once the Electoral College votes are cast, there’s still potential for uncertainty. That’s because Congress won’t formally certify the election results until January 6, 2021.

“It’s a mess in that period,” said Richard Hasen in an email. He’s a professor of law and political science at the University of California, Irvine, and has written about possible scenarios should a candidate die.

There’s much more certainty about what happens if the candidate dies between when Congress certifies the election and when he’s sworn into office on January 20,2021. In that case, under the 20th Amendment, the vice president-elect will be sworn in as president.

Perhaps a more likely scenario this year is what would happen if the election results were contested in some states.

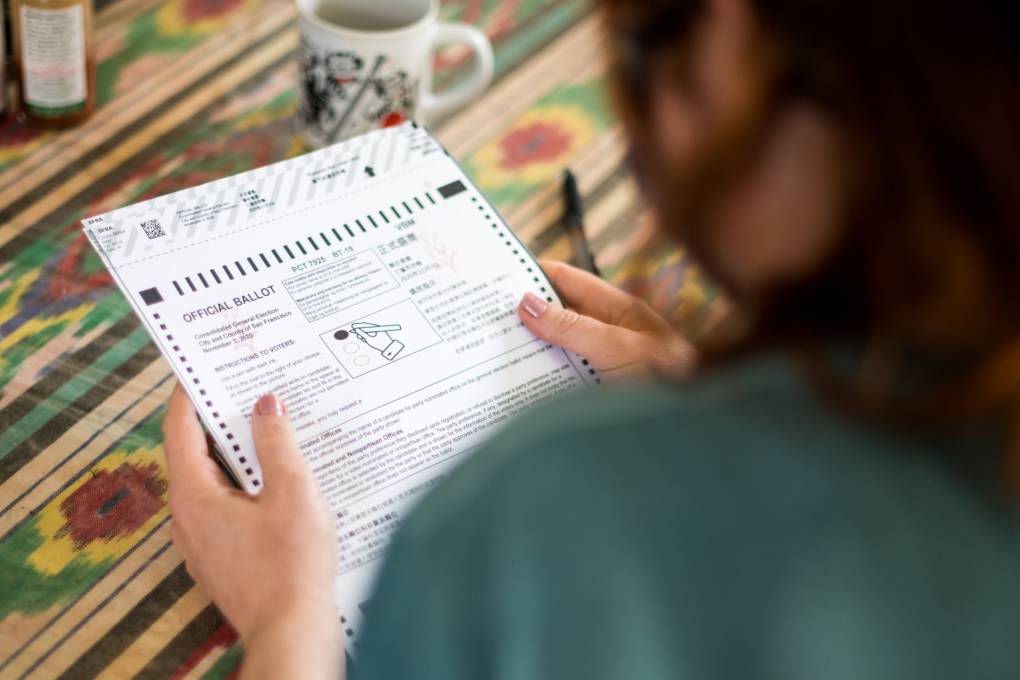

First, states have more than a month to count ballots, including the expected surge of mail-in ballots, and conduct recounts if necessary.

The courts will be mindful of when the electors meet in refereeing any disputes. For instance, during the 2000 election, the U.S. Supreme Court ultimately ended Florida’s vote recount, saying time had run out before electors were set to meet.