This is Part Two of the Bay Curious series on the Donner Party. Read Part One of this story here.

W

hen the snow finally melted in spring of 1847, the grisly evidence of the Donner Party’s ordeal — the things that had been buried under feet of snow at Donner Lake — were revealed in full.

Word of the Donner Party disaster had spread across the country and was already creating “lousy PR” for California, says Donner Party historian Greg Palmer. The story spooked would-be emigrants to the state, making officials wish “they could just wipe the slate clean.”

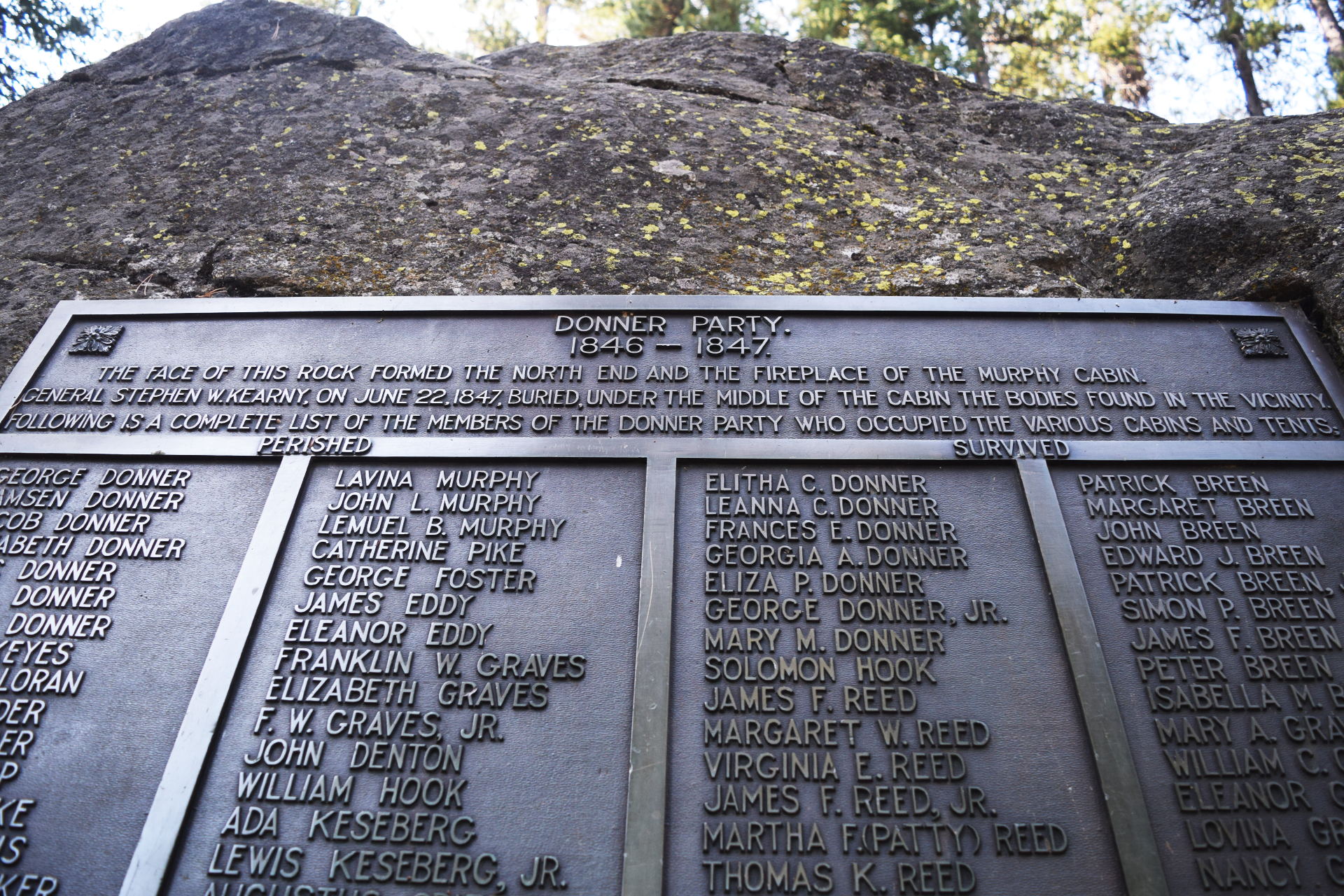

The solution was a California military detachment, led by Gen. Stephen Kearny. On their way over the mountains to Kansas in summer 1847, these men were given new orders to go to Donner Lake and clean up the mess.

Writer Edwin Bryant was with them — himself a recent emigrant who’d been on the Oregon Trail just ahead of the Donner Party. What he later wrote about that day was stomach-churning.

“Near the principal lake cabin I saw two bodies entire, except the abdomens had been cut open and entrails extracted,” Bryant wrote. “Their flesh had been either wasted by famine or evaporated by exposure to dry atmosphere, and presented the appearance of mummies.”

Bryant and the other soldiers were looking at what remained of the Donner Party: evidence of sheer desperation, and what it looks like when human bodies are stripped for food. “Human skeletons, in short, in every variety of mutilation,” Bryant wrote. “A more appalling spectacle I never witnessed.”

Bryant reported how that military party scraped all the remains they could find up from the forest floor, dug a hole in the floor of one of the cabins, and set fire to the whole thing: “With everything surrounding them connected with the horrible and melancholy tragedy, consumed.”

These soldiers weren’t just performing a physical clean-up job. They were taking a truly shameful part of the state’s history and erasing it from human sight. This new California demanded it.

Survivors in the Spotlight

As soldiers were burning the Donner Party’s dead up at Donner Lake, their family members who’d made it out alive were safe and warm miles away in the west.

A lot of the survivors spent the immediate aftermath recovering in present-day Sacramento at Sutter’s Fort. Presided over by colonizer John Sutter, this was the same place that had acted as a kind of Donner Party rescue command center during those long winter months.

Once the first survivors had escaped and brought the terrible news to California, public interest in the Donner Party saga soared. “The fact that it wasn’t just a bunch of mountain men … but these were women and children,” made it even more compelling, Palmer says. And of course, there was the cannibalism.

Like many people who find themselves at the center of disaster, the Donner Party survivors quickly found that other people were already writing their story for them. The same month that the last survivor, Lewis Keseberg, was rescued from Donner Lake, the California Star newspaper published an account it claimed was based on eyewitness accounts from the rescuers.

“A more shocking scene cannot be imagined than was witnessed by the party of men who went to the relief of the unfortunate emigrants in the California Mountains … A woman sat by the side of the body of her dead husband cutting out his tongue ; the heart she had already taken out, broiled, and eaten.”

The California Star cast the Donner Party as terrifying ghouls, so hooked on the taste of humans that they’d been somehow transformed by it into cannibalistic monsters:

“So changed had the emigrants become that when the rescuing party arrived with food, some of them cast it aside, and seemed to prefer the putrid human flesh that still remained.”

This account drips with revulsion at what cannibalism might have done to the Donner Party’s very humanity:

“Calculations were coldly made, as they sat around their gloomy camp fires, for the next succeeding meals… Language can not describe the awful change that a few weeks of dire suffering had wrought in the minds of the wretched and pitiable beings.”

A lot of what was published in the California Star is undoubtedly sensationalized, or just flat-out wrong. But this story, published hot on the heels of the disaster, set the tone for how California looked at the Donner Party, and it haunted the survivors for years.

Eliza Donner was just three years old when the Sierras orphaned her. It wasn’t until 1911 that she felt able to write her memoir, and to talk publicly about what she remembered of the disaster, but also about her life as a Donner Party survivor. In her book “The Expedition of the Donner Party and its Tragic Fate” she detailed how for years afterward, people came up to her and quoted that newspaper story.

“Evidently, it was written without malice, but in ignorance, and by some warmly clad, well nourished person, who did not know the humanizing effect of suffering and sorrow,” she wrote.

Two Survivors, Two Stories

A lot of the public outcry was directed at the final man to leave Donner Lake: Lewis Keseberg. Much of this was owing to another bit of lurid reportage, this time courtesy of one of the men who’d rescued Keseberg, Capt. William Fallon. He wrote how he “discovered Keseberg lying down amid the human bones, and beside him a large pan full of fresh liver and lights [lungs]”, and heavily insinuated that Keseberg had murdered Eliza Donner’s mother, Tamsen Donner, to consume her flesh and keep himself alive.

From almost the moment he came down from the mountain, Keseberg was a marked man. “Some declared him crazy, others called him a monster,” wrote Eliza Donner, who knew all too well how fast — and how effectively — the written word could be used against someone. She described “blood-curdling editorials” that were written about Keseberg, “stamping him with the mark of Cain, and closing the door of every home against him.”

Yet all the while, another man — the only actual, confirmed murderer of the Donner Party — received quite different treatment. It was no secret that William Foster had murdered the two Miwok men Luis and Salvador so that the first “Folorn Hope” group to escape Donner Lake could eat their flesh. But because of who he’d killed — two Native Americans, rather than a white woman like Tamsen Donner — Foster never faced a reckoning for his crime.

As Greg Palmer says, it wasn’t even seen as a crime. “‘They’re only Indian’: That was the mentality of the day,” he says.

What’s more, Foster had chosen to join the third rescue party, to voluntarily return to Donner Lake to bring more people to safety. To the white world in California, Foster was a hero, not a murderer —and condemning him would have meant condemning a mindset and a way of life that had greatly benefited many people who came to California to claim it for their own.

And the many more were about to make the journey.

The Gold Rush Takes Over

As brutal as the Donner Party’s life and death story is, the immediate aftermath actually marks a calm before the storm in California’s history.

In the short-term, the Donner Party horror scared people in California, but also would-be emigrants contemplating the same trip. The overland traffic of settlers in 1847 and 1848 dropped sharply, says Greg Palmer “because of what happened.”

In January, 1848, just nine months after final survivor Lewis Keseberg was dragged off the mountain, gold was discovered in California. As if to demonstrate the interconnectedness of the players in this period of time, that gold was found on land claimed by none other than John Sutter, on a site he was developing as an expansion of his Sutter’s Fort empire.

Those small flakes of gold in a river on Sutter’s land changed California forever — and most of all, for those Indigenous communities that had lived here for centuries.

Dahlton Brown is Executive Director for the Wilton Rancheria tribe in Elk Grove, outside Sacramento. And says he still finds it “just incredible” how the Miwok and Nisenan people of this region “could go from being the ancestral stewards of a place since time immemorial to just being a resource to be used, for the kind of capitalistic growth and entrenchment of an American society that hadn’t even been on this continent, established as a nation for 100 years.”

Earlier colonizers had already hugely disrupted the lives of California’s Indigenous residents. Settlers like the Donner Party had then wanted their land — and now with gold, everybody else did, too. White migration into California had been a trickle, but now it became a flood.

It’s estimated that in the first 20 years after gold was discovered, 80% of California’s Indigenous population was wiped out — not just by disease, but by destruction and murder. Those that survived found themselves displaced, and their customs, cultures and lives irrevocably altered — by design.

There were “insane restrictions put on our tribal communities that were meant to suffocate our life ways,” Brown says. These limitations were meant to “rob our communities and land, to make way for these miners and for these folks looking to make their riches.”

California had a new image, a new way of being. And everything that came before that didn’t fit was treated like dirt in the gold pan: discarded in the name of “progress.”

Hidden From Sight

As California bloomed under the Gold Rush, virtually all of the survivors of the Donner Party quietly, deliberately retreated from view, and scattered throughout the Bay Area and Northern California. For almost all of them, what happened up by Donner Lake was something they never wanted to talk about publicly.

If you’re imagining the remaining members of the Donner Party might have wanted to stick together, think again, says Greg Palmer. After what happened, there seems to have been very little desire to even speak to any of the others ever again. “There were animosities that weren’t forgotten,” Palmer says. “Which is totally natural.”

Of the families that entered the mountains, only two survived intact: The Reed and Breen families. Of all of the survivors, the Reed clan probably made the best of it — something you could attribute to the fact that patriarch James Reed hadn’t actually been trapped in the Sierras with his family. His earlier banishment from the trail ensured his safe arrival into California, where he’d been able to find time to do some land deals in San Jose while he was raising money to go rescue his wife and children. These included the purchase of the land where San Jose State University now lies.

When the Reed family escaped the mountains, they relocated down to the new home waiting for them in South Bay, where they settled into civic life with relative ease. After striking it rich in the Gold Rush, James Reed even became the Chief of Police in the San Jose Police Department. The family also welcomed two of the Donner family orphans into their home.

After recuperating at Sutter’s Fort, the Breens quietly moved south to San Juan Bautista, outside Gilroy. The other survivors, who had all watched at least one family member die in the Sierras, scattered more quietly around Northern California — from Petaluma and Sonoma to Sebastopol and Tomales Bay. Marysville, just outside Yuba City, is named after one of the Donner Party survivors, Mary Murphy.

And what about Lewis Keseberg, the man who had ‘cannibal’ yelled at him in the street? He sued a bunch of people for calling him a murderer — but the judge sneeringly awarded him damages of just one dollar in each case. He lived for almost fifty more miserable years after being dragged off the mountain, beset by misfortune and bereavement.

Lansford Hastings, the entrepreneur whose wrong-headed guidebook was the blueprint for the Donner Party’s demise, became a lawyer in San Francisco, and then abandoned it to go into the Gold Rush business with none other than John Sutter. Even Sutter — the enslaving colonizer — described Hastings as “a bad man.”

Hastings then became a Civil War major, on the Confederate side. Having been at least the semi-architect of one disastrous journey, his last voyage was to Brazil, where he was attempting to start a colony for Confederates. He died on the ship on the way.

Many of the survivors never even spoke about that winter with their own families, says Greg Palmer. “I guess you could call it the code of silence, remembering that this is the Victorian era … speaking of anything that’s very personal, particularly something as taboo as eating the flesh of people was just not done. And so the shameful stigma of it pervaded most of the members.”

When you remember that first newspaper story in the California Star, who could blame them? The public seized on what they’d read and if anything, remembered it as even worse. Eliza Donner recalled being taunted by a stranger years after the disaster, who “insisted that the Donner Party was responsible for its own misfortune” and who proclaimed “that he himself felt that the miserable wretches brought from starvation were not worth the price it had cost to save them.”

Perhaps this new California — swollen with people, gold and self-regard — didn’t want any reminder of early failures. Desperation and degradation, after all, hardly makes for a satisfying origin myth.

A Legend Resurrected

For three decades after the disaster, little more was heard from or about the Donner Party survivors. But in 1878, a historian and newspaper editor in Truckee named Charles McGlashan had a chance encounter with a Donner Party survivor. This was James Breen — who, like Eliza Donner, had only been a tiny child when his family lived through the disaster. But the meeting was enough to get Charles McGlashan instantly obsessed with this local, infamous history.