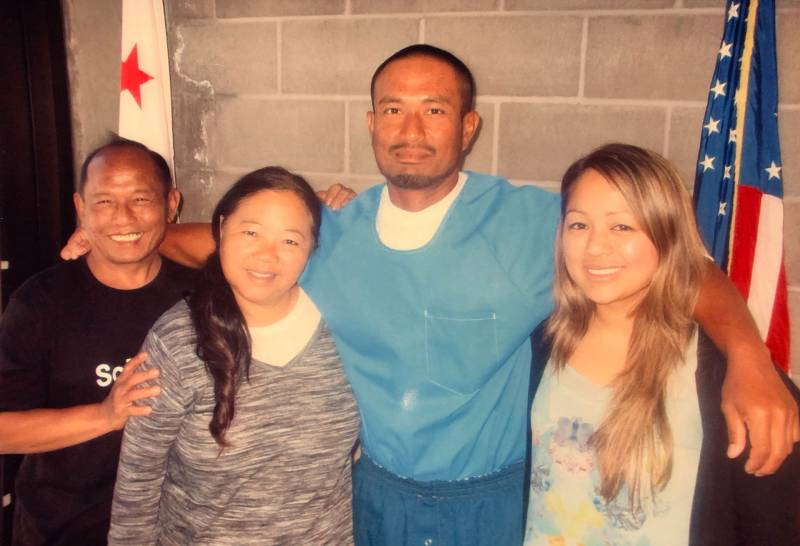

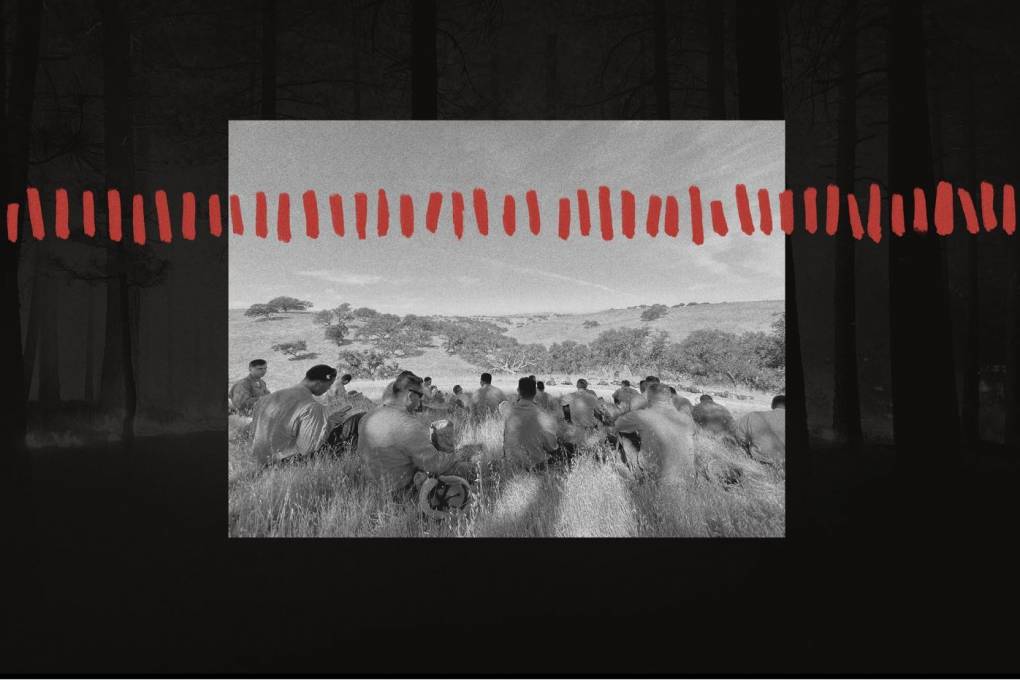

Among the roughly 1,800 inmate firefighters who battled record-setting blazes in California this year was Bounchan Keola, a 39-year-old immigrant serving a 28-year prison sentence for a gang-related shooting when he was a teenager.

Keola, who grew up in the East Bay city of Richmond after fleeing Laos with his parents when he was just 2 years old, battled six major wildfires in California this season. During an assignment on the Zogg Fire this fall in Shasta County, he suffered a traumatic neck injury after being hit by a falling tree and had to be airlifted out and hospitalized.

But despite the physical pain he still suffers and the dangerous work firefighting represents, Keola still wants to do it.