On Dec. 23, just two days before Christmas, the number of active COVID-19 cases in Alameda County’s Santa Rita Jail shot up from five to 56, the Alameda County Sheriff’s Office reported in an easily overlooked post on Twitter.

'I'm the Only One Doing It': The Cal Law Student Tracking COVID-19 Cases at Santa Rita Jail

Sgt. Ray Kelly, a spokesman for the Alameda County Sheriff’s Office, which runs the jail, says it’s the second outbreak at the facility since the pandemic began, despite a set of protocols in place to ward off the virus.

“We’re testing people who come into the jail and then we’re testing people two weeks after they’ve been in the jail,” said Kelly, noting that employees of the facility are screened on a regular basis, and everyone inside, including those incarcerated, have access to personal protective equipment and hand sanitizer.

But Darby Aono, a second-year law student at UC Berkeley, believes much more could be done to improve safety inside the jail. Aono has been tracking COVID-19 cases in the jail since the pandemic began in March and says she’s the only one making that data publicly available.

The Sheriff’s Office tweets out regular updates about infection rates and lists total daily case numbers and testing data on its website. But it does not provide a public record of that data over time, information she contends is essential.

“It’ll be like they’ve tested like 6,000 people [total] and they have one case,” she said. “But if you look at the historical data, it’s like, oh, wait, they only actually tested 7% of the entire jail in the past week.”

Aono says the data from the Sheriff’s Office “provides this veneer of transparency” that’s largely presented out of context.

When the pandemic began, she says, “a lot of advocates were saying Santa Rita was going to be a hot spot because they have taken such notoriously poor care of people in the past.”

As the Alameda County Sheriff’s Office began sharing case information on Twitter, Aono put it into a spreadsheet — one she continues to update.

She says she’s contacted The Marshall Project and the UCLA School of Law — both of which report on prison rights issues — but says no one seems to have the bandwidth to take over the task of keeping track of cases in the jail.

“I should not be the one tracking it, Aono said. That’s patently absurd, that some random law student is the one keeping track of people’s lives — they matter so much more than that.”

“Because I’m the only one doing it, I’ve just kept doing it,” she added. “I’m not good at Excel, but I just do it everyday.”

Kelly says that unlike individual counties and the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, his office doesn’t maintain a public dashboard of cases, which he claims would be too costly and time consuming. But he says Santa Rita has been one of the most transparent jails in the state since the beginning of the pandemic.

As of Jan. 4, the Sheriff’s Office reported 80 positive cases, with 195 people recovered and in custody and another 92 recovered and released.

But Aono says the jail should be doing more to stop the spread by more aggressively testing everyone inside and isolating those who are infected.

“There is no doubt in my mind that they’ve been in this outbreak for a while and we just don’t know about it because the testing rate has been so abysmally low for so long,” she said.

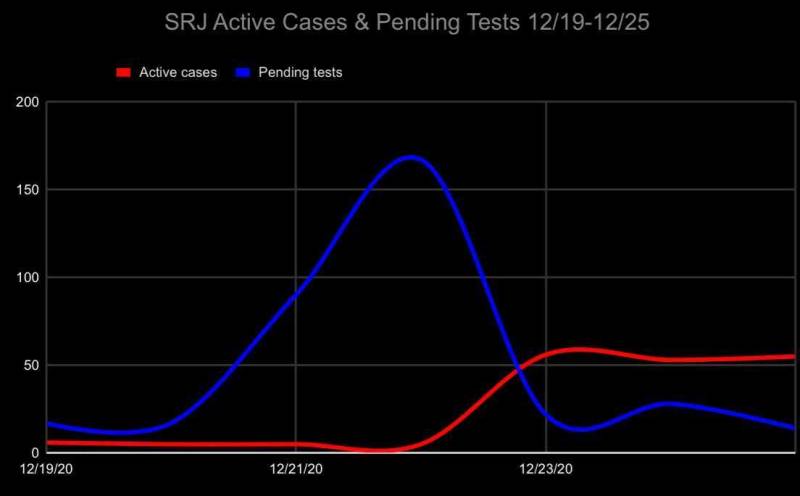

Aono also points to data from her spreadsheet suggesting that when cases within the jail spike, the testing rate drops.

Kelly, however, denies this.

“I think we go to the the source of the outbreak. And obviously, if we weren’t testing, then you wouldn’t have those spikes,” Kelly said. “But we see a lot of asymptomatic results.”

Kelly says the Sheriff’s Office has, overall, been “very, very successful at keeping inmates safe. … We’ve had very, very little complications at all.”

Lina Garcia Schmidt, who runs a jail hotline in collaboration with the National Lawyers Guild, supports Aono’s contention that testing rates have been intentionally low. She says she recently spoke to a 45-year-old incarcerated person at the jail who told her he had requested a COVID-19 test on four separate occasions and was refused each time.

“We suspect it’s a way of suppressing the number of infections,” she said.