Two years ago, Dr. Tung Nguyen launched PIVOT, a progressive nonprofit that provides information to Vietnamese readers about everything from politics to American culture. Then came the pandemic, and he noticed family members and people in his community spouting misinformation.

‘Cultural Brokers for Our Families’: Young Vietnamese Americans Fight Online Misinformation for the Community

“Particularly on YouTube, there are some very high trafficked [sites], and I’m not sure where they are coming from,” said Nguyen, an internal medicine specialist at UCSF. “They seem to have a lot of people listening to what they say, and a lot of what they say is not accurate.”

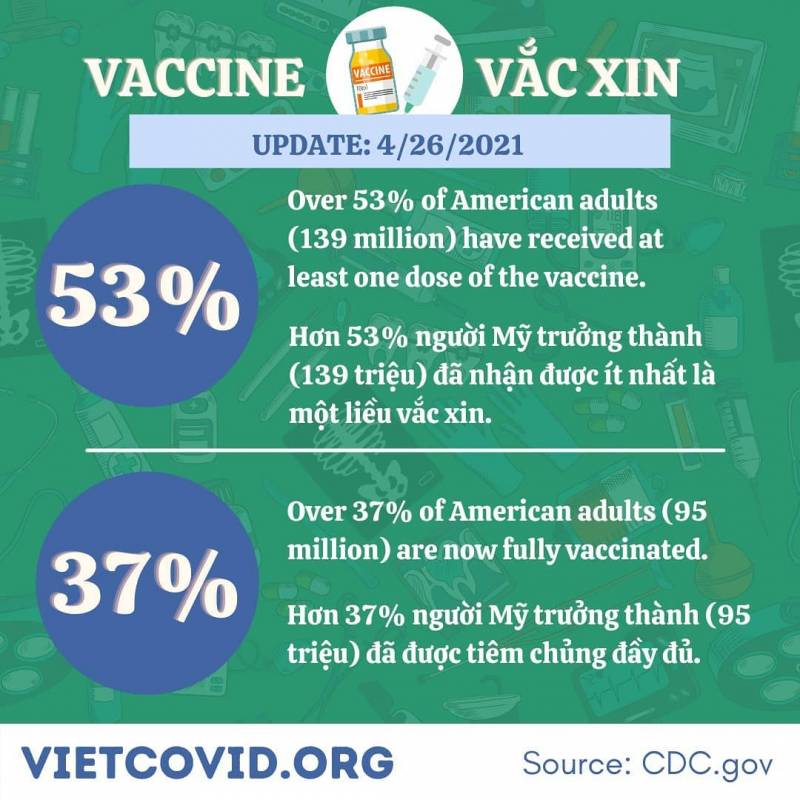

So in December, right before the vaccine became available for distribution, Nguyen launched an offshoot of PIVOT, VietCOVID.org, to share accurate information in Vietnamese about the virus, how it spreads and what people can do to protect themselves.

Many younger Vietnamese Americans with a limited grasp of medical vocabulary in Vietnamese, he explains, face a credibility gap speaking to their elders. “The younger people may know the science, but they can’t explain it in a way that actually makes them credible in Vietnamese. Of course, if they do it in English, the older people won’t know or care.”

Nguyen says his goal to help younger Vietnamese Americans speak with authority to their elders about the virus and the vaccine. “We create materials in both English and Vietnamese so that the English speaking people can read it and understand what it says and can point the Vietnamese part to their family members,” Nguyen said.

San Jose is home to one of the largest Vietnamese American communities in the country, and it’s one of the hardest hit by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Misinformation and YouTube

A YouTube spokeswoman told KQED the social media giant employs more than 20,000 content screeners globally, but declined to specify how many of those focus specifically on Vietnamese content, either in Vietnam or in the United States.

It’s not difficult to find YouTube channels spouting misinformation about the pandemic in Vietnamese – misinformation that’s often couched as personal opinion – to tens of thousands of subscribers. And YouTube’s community guidelines don’t always stop certain channels from spreading harmful content.

KQED brought one such video in Vietnamese to YouTube’s attention. It was from a channel with more than 96,000 subscribers which has been suspended twice for violating YouTube’s content guidelines. YouTube didn’t remove the video from its website because a spokeswoman said it didn’t violate its guidelines.

But Nick Nguyen, a board member with PIVOT and a writer for Viet Fact Check, worries the video still spreads harmful misinformation. He argues YouTube’s promise to combat misinformation takes a back seat to its monetization of popular channels, especially when the channels operate in languages other than English.

“If they are responsive to our small community, then they will have to spend time and money on other groups who fairly ask, ‘Why aren’t you taking down this content in Farsi or Spanish?’ ” Nick Nguyen said.

Cultural Brokers in a Pandemic

In the absence of effective misinformation control, a number of young Vietnamese Americans have been taking matters into their own hands.

Peter Lai in Connecticut started an Instagram account called Viet Fake News Buster, where he pinpoints parts of YouTube videos that spread misinformation and encourages his followers to flag the videos for YouTube to take down. In Southern California, young Vietnamese American volunteers translate news articles from English into Vietnamese for The Interpreter.

In the South Bay, there’s the Vietnamese American Roundtable, which had organized webinars for local Vietnamese American business owners on shelter-in-place guidelines on Facebook, and sent those who sign up for them vaccination alerts in Vietnamese.

“This information needs to be out in Vietnamese and there’s no one go-to, or yellow page, or a one-page resource for all our community that is translated into Vietnamese,” said Vietnamese American Roundtable Secretary Christina Johnson.

She added that the information needs to be more than accurate, but culturally nuanced, too. For instance, she points to Santa Clara County information about COVID-19 and sheltering in place in Vietnamese as technically accurate, but culturally “clumsy.”

Consider the word “census.” In Vietnamese, too, it means a count of people.

“But the word could also be used as investigation,” Johnson said. “When Vietnamese people, like older folks, hear the word ‘investigation,’ it harks back to the communist era. ‘Why are you investigating me? Why do you need to know this information? How is it going to be used?’ ”

“We’ve grown up being cultural brokers, informational brokers for our families,” Johnson said. “Now we’re really utilizing that skill and expanding it to do it for our communities.”

Regardless of misinformation, she says familiar peer pressure is a strong driver for vaccine skeptics to overcome their doubts and get the jab.

“After my husband got it, my grandparents got it, her sister and her brother got it. It was, like, “OK, people around me are getting it so now I’m going to get it,’ ” Johnson said.

This story has been updated.