California’s future political lines are being drawn and debated in a once-in-a-decade process that could strengthen political representation for the Bay Area’s growing Asian populations.

The redistricting is being carried out by a citizen panel whose decisions are rooted in the population changes reflected in the 2020 Census. In the last decade, California’s population that identifies as “Asian alone” grew by 1.2 million (25%) including an increase from 1.6 million to 2.4 million in the nine-county Bay Area (29%). In addition, California saw a 37.9% jump in people who identified as “Asian in combination” with another race.

In percentage terms, the state’s Native American population saw the largest growth (74%) of any group in California.

Those trends could result in more districts where Asian voters are either a majority or a powerful voting bloc. That, in turn, would require candidates to prioritize the issues that unite the region’s diverse Asian communities, such as culturally specific social services and protection against anti-Asian violence — or directly lead to the election of more Asian representatives, said Lee.

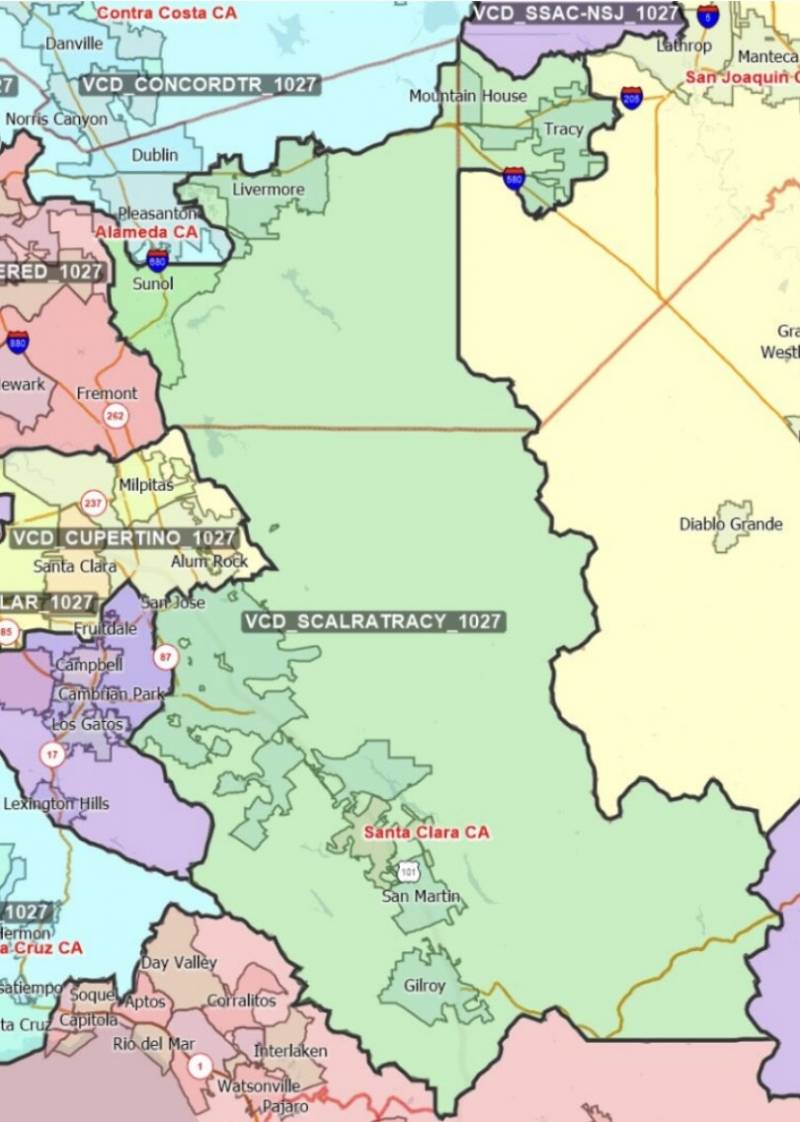

But political line drawing comes with trade-offs, and the commission is sure to draw fire for the communities they chose to group and split in a series of draft maps released this week.

“Redistricting is more art than science,” said David Lee, executive director of the Chinese American Voters Education Committee.

“Anybody can sit here and numerically move blocks along until you get a balanced district, but the art comes in terms of understanding the political implications of these moves,” said Lee. “What race or ethnicity might have a leg up if you draw the district one way or another?”

A clear goal of drawing political lines in the new maps, said Lee, is to give an expanded political voice to growing communities.

That political tapestry is in the hands of the California Citizens Redistricting Commission, a body of 14 residents created when voters passed Proposition 11 in 2008, taking the line-drawing powers away from the state Legislature.

The commission’s first priority is to draw maps of roughly equal size: roughly 1 million residents per state Senate district, 800,000 for congressional seats and 500,000 in each state Assembly district.

After that, said Commissioner Isra Ahmad, the maps must comply with the federal Voting Rights Act, which ensures that people of color have a fair shot at electing representatives of their choice.

“This really is to ensure that [people of color] have an equal opportunity, and it is tied to the historical exclusion of [these] groups in their power of voting,” said Ahmad, a Santa Clara County researcher.

The commission also tries to keep cities, counties and self-described “communities of interest” together, and to draw the districts in compact shapes.

When the state Legislature ran the district-drawing process in 2001, they prioritized the protection of their own incumbent lawmakers over uniting neighborhoods like Berryessa, a predominately Asian community in north San José.

“That particular neighborhood got chopped up so that it was then put into four different state Assembly districts and two different state Senate districts,” remembers Richard Konda, executive director of the San José-based Asian Law Alliance.

Berryessa residents and businesses were such a small voice in each of the districts that their concerns were easily overlooked by local representatives, said Konda.

In 2011, members of the community brought their concerns to the new citizens’ commission, and new lines reunified Berryessa in the most heavily Asian populated Assembly, Senate and congressional districts in California.

Ten years later, census results could push line-makers to draw more districts with a sizable share of Asian voters.

“When I’m thinking about the dynamics of the Bay Area, the main thing in my mind is what’s going to happen with [representation of people of color] — in particular, how is this growth in the Asian American community going to emerge?” said Eric McGhee, senior fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California.

As the redistricting process got underway, delayed by the late release of census data, a network of Asian American, Pacific Islander, Arab, Middle Eastern, Muslim and South Asian advocacy groups formed the AAPI & AMEMSA State Redistricting Collaborative.

The group held local workshops for residents and drew its own series of district proposals, presenting the commission with maps that already had community input baked in.

“We got a lot of really great, rich information and tried to make sure folks were sharing that with the commission,” said Julia Marks, an attorney with Asian Americans Advancing Justice – Asian Law Caucus. “But fitting all these communities and data and legal requirements together to create an actual map proposal is a big puzzle.”