Nance Parry says she’s sent out more than 1,000 résumés since she got laid off in September 2019. She’s gotten one interview.

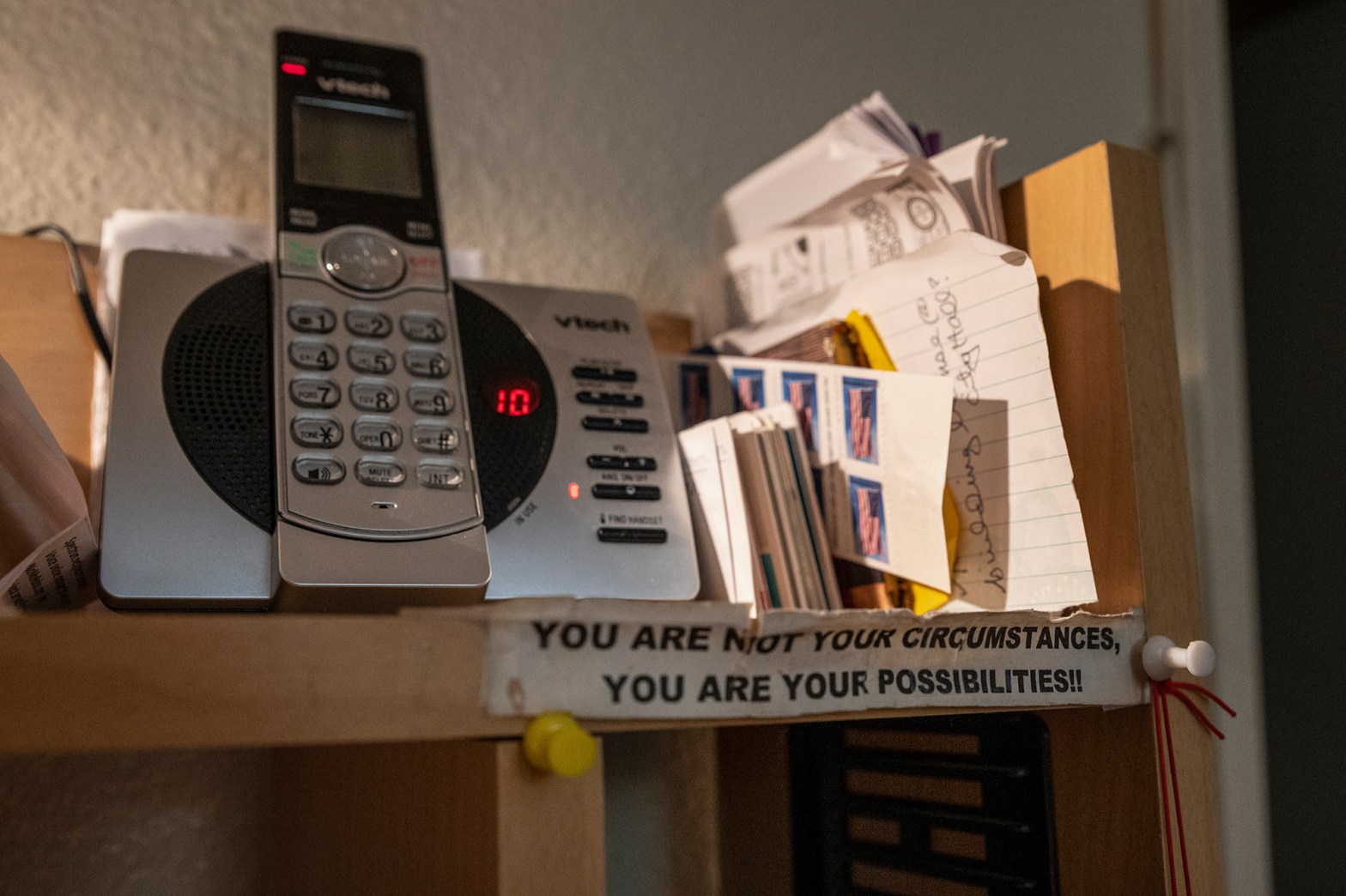

Just five weeks into what Parry thought would be a six-month contract, she was laid off from a job as a document specialist for an engineering firm. She says she’s sent out two to three résumés per weekday since but that’s netted a grand total of one interview, leaving her to live off a monthly $1,200 Social Security check, $1,030 of which is used to pay rent for her apartment in Duarte.

“I’ve tried to survive, you know, paid bills and food and everything on $200 a month after the rent is paid,” Parry said. “I need to work.” She needs new glasses and electrical work done on her car, but won’t be able to pay for either of those things until she gets a new job. Her landlord has tried to evict her three times, she says, and she’s worried about what will happen when LA County’s eviction protections end in January 2022.

“I don’t know if I’m going to end up living in my car or what because without a job you can’t get an apartment,” she said.

Parry is one of roughly 1.4 million Californians who are out of work and looking for jobs. In October, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the state recorded a 7.3% unemployment rate, the highest in the country, a distinction California shares with Nevada. October’s national unemployment rate is several points lower, at 4.6%.

One contributing factor to the state’s lagging employment situation is that California’s large leisure and hospitality sector — made up of hotels, restaurants and more — hasn’t rebounded as quickly as the rest of the country’s. But other data suggest the news isn’t all bad: There are lots of job openings, and workers are quitting their jobs in droves, which is often a sign that people are optimistic they can find a better job.

Why is California's jobless rate bouncing back more slowly?

Even pre-pandemic, California’s overall unemployment rate was usually slightly above the national rate. But the fact that so many Californians work in the leisure and hospitality industries — which saw massive layoffs at the beginning of the pandemic — contributes to the state’s lagging employment recovery now. Leila Bengali, an economist at UCLA’s Anderson School of Management, pointed out that California’s leisure and hospitality sectors employed almost 18% fewer people in September 2021 than pre-pandemic, according to data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Nationwide, the industry was just 9% smaller in September than it was pre-pandemic.

One explanation for the gap between the rate at which California’s leisure and hospitality industry has recovered jobs and the rate at which the industry has recovered jobs nationally, Bengali said, is that international tourism, a large part of the state’s economy, was particularly hard hit during the pandemic. Visitors buy lunches at cafés and stay in hotels; when travel dried up, those businesses bore the brunt.

“It’s not a coincidence that two states [California and Nevada] that are heavily reliant on tourism and entertainment have not done as well, given the demise of tourism and entertainment under COVID,” said Manuel Pastor, a professor of sociology and American studies and ethnicity at the University of Southern California.

New York, which also has a large tourism industry, has an overall unemployment rate of 6.9%. Florida, another high-tourism state, stands apart among high-tourism states with a 4.6% unemployment rate overall. The leisure and hospitality sectors in California, Nevada, New York and Florida all have added jobs back more slowly than the sectors have nationally.

Another potential explanation comes from research by Harvard economics professor Raj Chetty and several other economists, who found that lower-wage workers who worked at small businesses in high-rent ZIP codes — of which California has many — lost their jobs at higher rates early in the pandemic than lower-wage workers who worked in small businesses in lower-rent areas.

“If you lived in East LA, but you got on your bike and a bus to get over to Beverly Hills to work in a restaurant, or to clean a house or to take care of kids, a lot of that demand disappeared,” said Pastor.

But aren't employers struggling to fill jobs?

Yes. Walk down any commercial strip in a California city and there’s a decent chance you’ll see a "Now Hiring" sign in a restaurant or shop window. Employers have been offering cash bonuses and beefed-up benefits to fill empty positions.

California’s unemployment situation “certainly isn’t a question of a lack of job opportunity. That’s not what’s going on,” said Chris Thornberg, founding partner of Beacon Economics, an economic research and consulting firm. “There are an insane number of job opportunities in our state and in the nation overall.” People may just be taking their time to find a good job, he said.

There are also some indications that lower-income families aren’t experiencing economic stress, said Thornberg. For example, the share of Californian consumers with new bankruptcies is lower than it was pre-pandemic.

A lot of the job openings also require in-person, physical work with unpredictable hours — like serving in a restaurant, or packing goods in a warehouse. Some people aren’t willing or able to do that work.

Parry is worried about working in person while the pandemic is ongoing. “I keep seeing signs in restaurants and stuff like that. It really makes me feel bad because I need work,” she said. She worked at Cost Plus over the holidays once in the past, and it made her legs hurt. “I am 71 years old,” she said. “I mean, the last thing I want is a job where I stand all day because it kills the legs and the back.”

“I think right now we’re seeing a lot of people move out of retail, leisure and hospitality and start looking for other employment,” said Somjita Mitra, chief economist at the California Department of Finance. Unpredictable schedules make it hard for workers in those industries to find child care and use public transit to get to work. “There’s going to be some structural changes in those industries long-term,” she said.

It's not all bad

Compared to California’s jobs recovery after the Great Recession — when unemployment peaked around 12.6% and took more than four years to get down to the state’s current 7.3% unemployment rate — the state’s post-pandemic recovery has been a roaring success. During the pandemic, unemployment in the state crested at 16%, but just a year and a half later, that number had fallen by more than half.