It was 1945 in Quảng Bình, the thin north-central neck of Vietnam, and famine ravaged the country. A newborn baby wailed in a sugarcane field, announcing her arrival with a rawness that would later become her signature. Giving birth indoors was thought to be bad luck, so Nguyễn Thị Tâm — or Tâm — was born outside. A fortuneteller said she would be famous one day.

Still, by adolescence, Tâm didn’t seem destined for traditional greatness — which in Vietnam usually meant academic achievement. Her family moved to Hóc Môn, a district outside the southern capital of Saigon. Here, she failed to enter the prestigious Gia Long Girls’ High School.

But Tâm didn’t care; she had music.

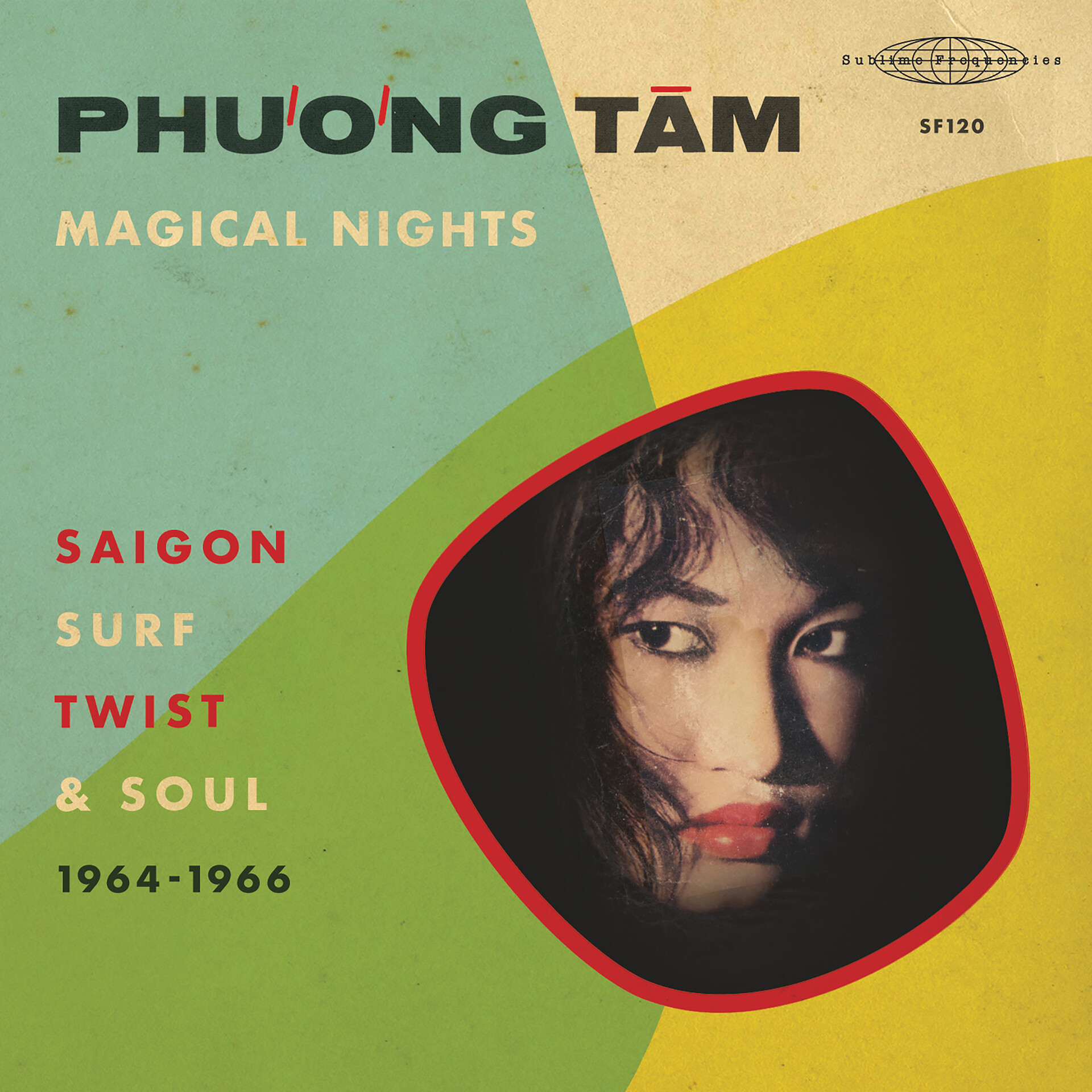

By 19, under the stage name Phương Tâm, she shared album covers and marquees with Saigon’s most sought-after singers, musicians and composers.

Phương Tâm peaked from 1964 to 1966, and then disappeared into obscurity for over 50 years.

She married a doctor and had three children, living a suburban life in San José. It wasn’t until recently, with the encouragement of her oldest daughter, Hannah Hà, did Phương Tâm at age 77 reclaim her identity as Vietnam’s first rock-and-roll queen.

Growth of a star

Tâm’s father kept the family’s single radio set on BBC News. So, as an adolescent, Tâm found her musical fix in the cacophony of her village courtyard. It was the late 1950s, and American pop music was beginning to influence Vietnamese tastes — which had previously included folk opera, French jazz and bolero. Tâm lingered by a neighbor’s window listening to songs like Connie Francis’s “Lipstick on your Collar,” and rapidly copied the beats and lyrics she didn’t understand.

At 16, Tâm won a singing competition and was accepted into Đoàn Văn nghệ Việt Nam, a program to create live entertainment for military personnel. It was good money, but eventually Tâm ditched the propaganda music — and high school.

She found mentors who shared her love of Western music. One well-known musician, Nguyễn Văn Xuân, took her on as a private student. He gave all his best students stage names, so Tâm became “Phương Tâm.” It meant “the direction of the heart.”

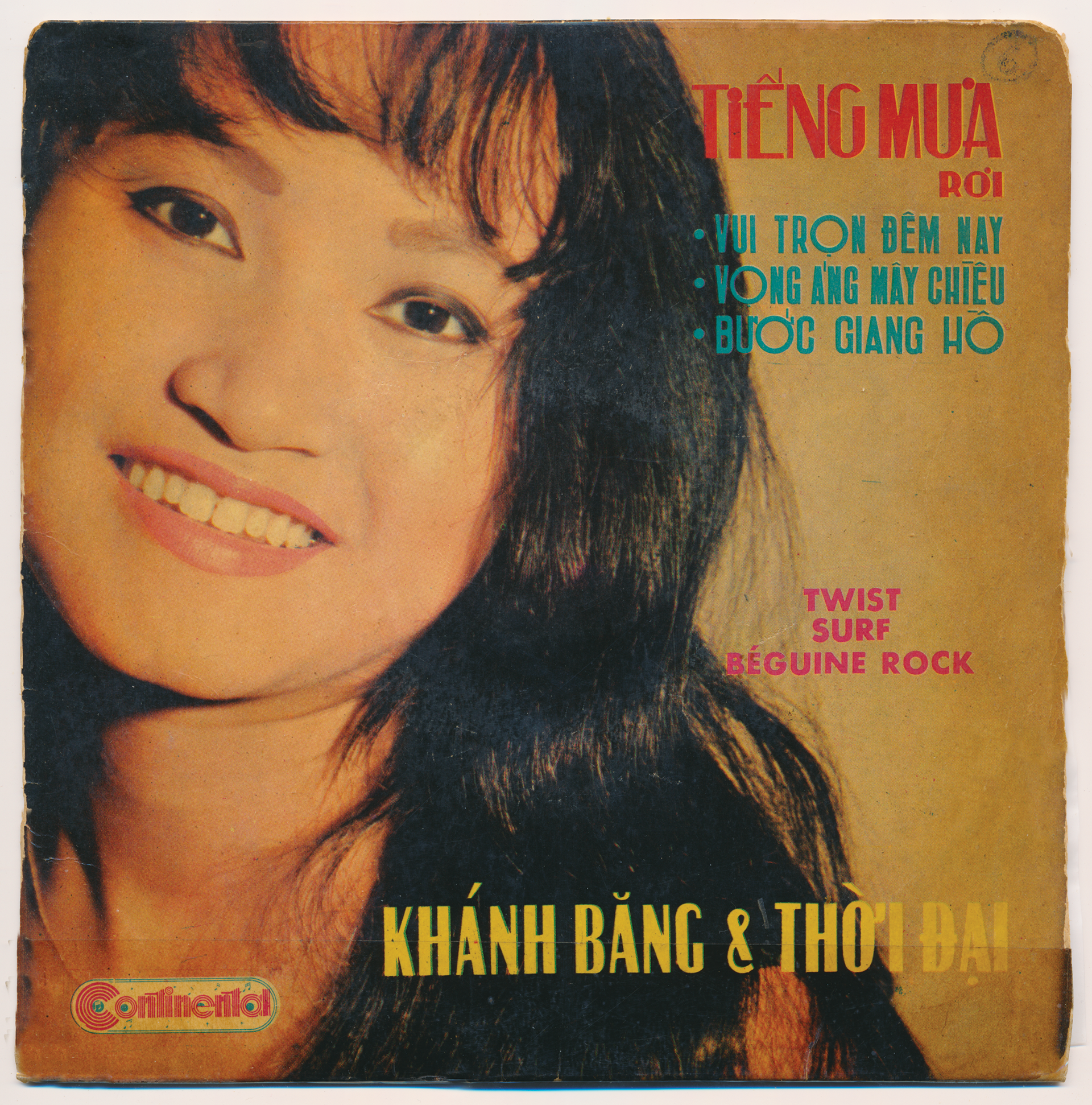

Her name change signaled her rise to fame. Phương Tâm headlined the nightclub circuit, and she collaborated with famed composers and musicians, including Khánh Băng, one of the first Vietnamese people to perform with an electric guitar. The major Saigon labels — Sóng Nhạc, Continental and Việt Nam — recorded her songs.

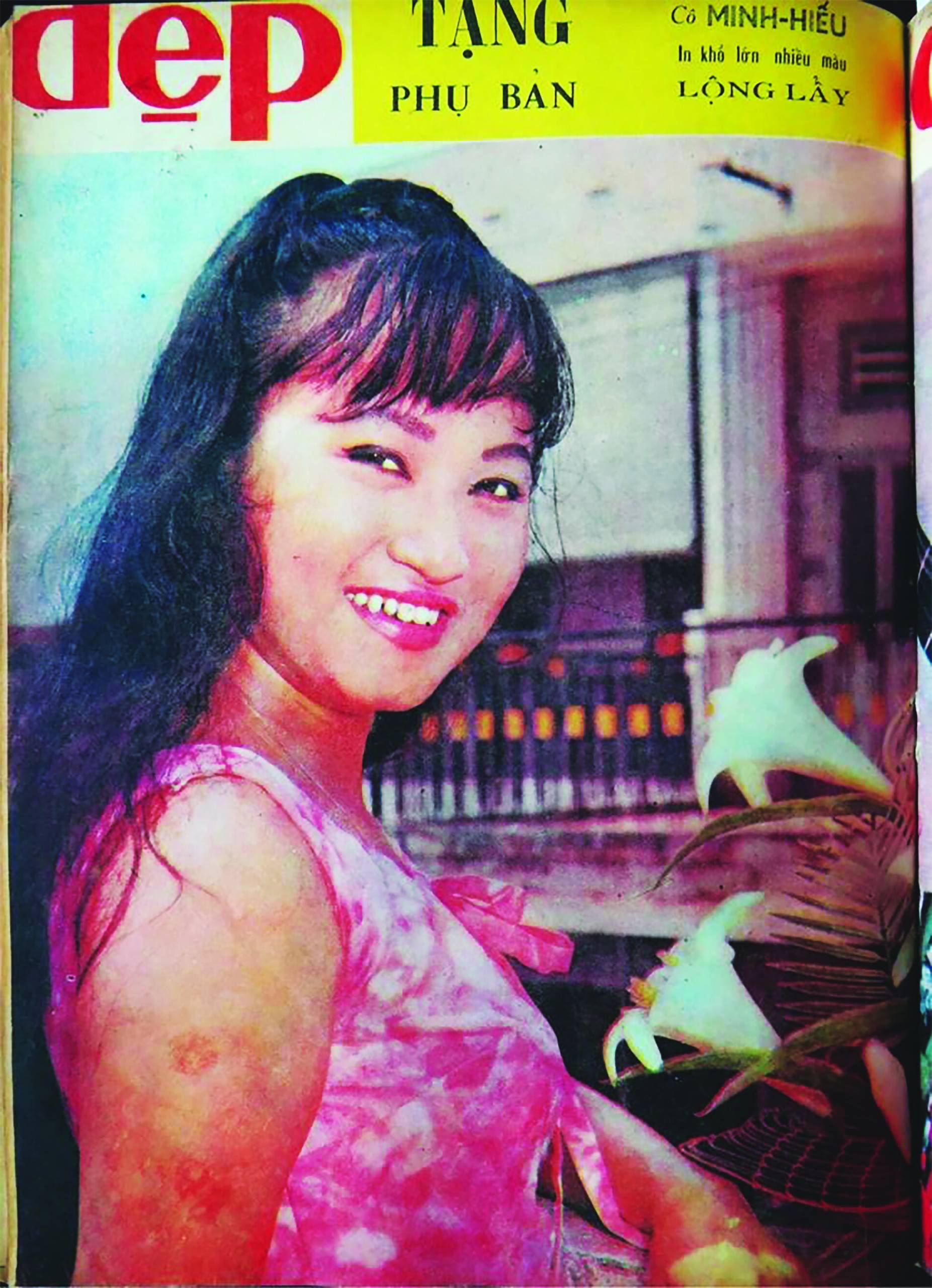

Her style of singing wasn’t just “sexy-naive,” a common trope that continues to have appeal in Vietnam today, but also at times was downright loud and raucous. In spite (or because) of the subversive nature of the music she sang, Phương Tâm kept her clothing modest.

“At night I always wore áo dài, but always wore white or beige, not bright,” says Tâm, sitting in her living room in San José.

The áo dài was the wispy national dress of Vietnam, made famous by pictures of schoolgirls. But Phương Tâm wasn’t your average schoolgirl. In a music review from 1962, famed Vietnamese writer Mai Thảo wrote in “Kịch Ảnh” (“Drama”) magazine about the simmering power of this modestly dressed teen:

“As she steps from the back and moves toward the microphone with glittering eyes her hands clapping to the beat — a new shape emerges. The figure is now drawn with burning flames, like a green fruit ripening before your eyes.”

Phương Tâm, like other performers, would chạy số — which literally translates as “run numbers.” The phrase described the high-speed nightclub runs that were common for performers at the time: 5 p.m. at Tân Sơn Nhất Air Base, 7 p.m. at An Đông, 8 p.m. at the Capriccio Bar — then to Tự Do. And so on, every hour, three songs per venue. At midnight, she finished with an hour-long set at the Olympia.

Tâm had an admirer, an officer who followed her from one venue to the next. He loved it when Tâm sang “Tenderly.” The officer told her it reminded him of her “enticing lips.” She kept her distance.

November 1963 signaled a significant change for South Vietnam. The president, Ngô Đình Diệm, was assassinated. The details of the event remain murky, but American involvement and military presence increased. The nightclubs catered to a growing military clientele. One night that month, Tâm’s admirer brought along a young new military doctor, Hà Xuân Du. There was something different about the young doctor, Tâm recalls.

“He asked me for my address, and the day after, he came to my house,” she says.

They started dating, and “Tenderly” became their song. But Phương Tâm and Du’s marriage almost three years later — between a singer and the son of an elite family — was scandalous. Their parents didn’t come to their wedding.

“They don’t accept me, but … we were already in love,” says Tâm.

A different life

In 1966, as quickly as Phương Tâm ascended to fame, she left her singing career — without a goodbye tour or a last interview.

Tâm followed her husband to Đà Nẵng Air Base, just over 100 miles south of the demilitarized zone that separated North and South Vietnam. Between 1967 and 1968, the war — and the bombing — intensified. Tâm sheltered with her three children.

“The rockets would go … the sirens!” recalls Hannah, Tâm’s oldest daughter. “Whenever we would hear the sirens, we would go into the bunker.”

Hannah remembers hiding for days at a time in that oppressively hot single room with a refrigerator.

With the fall of Saigon in 1975, the family evacuated on a cargo plane. They eventually arrived in Southern California. There, Tâm found work — mostly random, repetitive piecework for the garment industry. She sewed, but not well.

“I only knew how to sew in a straight line,” Tâm says with a shrug and an impish laugh. She made $0.10 a garment cutting loose thread. Meanwhile, her husband studied to requalify to practice medicine.

“I’d come home every day and there’d be a burnt pot,” says Tâm. Du would try to boil a pot of water for coffee and get distracted either by studying or watching sports.

Life for Tâm revolved around the kids and, by 1980, supporting Du’s successful pediatrics practice in San José.

“It was always cooking, cleaning, going to work, disciplining us, making sure that we were well behaved,” recalls Hannah of that time in her family’s life.

Eventually the family acquired the trappings of Vietnamese immigrant success, right down to the white leather couch in the living room. The couple developed strong ties with people in the Vietnamese diaspora, with a special appreciation for music.

“When my then-boyfriend — now husband — came to visit my mom for the first time, he had to sing two songs on the karaoke machine: ‘I’ve Got You Under My Skin’ and ‘My Way,'” says Hannah.

Her parents graduated beyond simple karaoke, however. Their parties included a who’s who of Vietnamese pre-1975 musicians, including Nguyễn Ánh 9, who ‘d once backed Tâm on the guitar in Vietnam.

Tâm’s past life as a singer was an open secret. She didn’t deny it — but she stuck to singing other people’s hits, not her own.

When her husband Googled her a few years ago, he found videos that purported to feature Phương Tâm. “‘Oh, my God, what woman is doing this! Look at this! Who ever put this video up and use your name?'” Hannah remembers her father saying. For Du, there was only one Phương Tâm: his wife.

To make things more confusing, there was another singer with a similar name, Phương Hoài Tâm, also in San José. This woman ran a skin care salon while performing on the side.

A new chapter

“My mom and my dad were always a couple,” recalls Hannah. “Wherever they went, over to their friend’s house, it was never without the other.”

Then in 2019, Tâm’s husband Du died after a prolonged illness.

Vietnamese people often make an altar in their homes to honor the dead. Commonly, the altar pictures are static: a face either in a formal pose, or a slightly brighter version of a passport photo.

But in Tâm’s home, her beloved is holding a microphone, singing.

Du’s death was a turning point for Hannah and Tâm. Hannah went searching for more information about her mom’s past life. She stumbled across compilations of Vietnamese wartime rock music, including the most successful album to date, called “Saigon Rock and Soul: Vietnamese Classic Tracks 1968-1974.”

The album attributed one song, “Magical Night,” to Phương Tâm. Hannah couldn’t be sure it was her mom’s voice. And when she showed Tâm the cover — featuring a woman in a menswear jacket, cap and tinted oversized glasses smoking a cigarette — Tâm’s reaction was swift.

“Oh, they are liar! I never smoke!” Tâm said, according to Hannah.

Hannah contacted Mark Gergis, the producer and audio archivist who compiled that album. Gergis, who is originally from Oakland but now lives in London, has spent two decades focused on diasporic Middle Eastern and Southeast Asian music.