The spokesperson, who would not agree to be identified because he was not authorized to speak about the case, said ICE makes custody determinations on a case-by-case basis, “considering the merits and factors of each case while adhering to current agency priorities, guidelines and legal mandates.”

The news came as a surprise to Yung’s supporters, who had held a rally in Los Angeles Friday morning calling on California officials not to cooperate with ICE.

“We’re relieved it was dropped and he’s not going to be transferred to ICE and he’ll receive the care he needs after leaving prison,” said Anoop Prasad, Yung’s lawyer with the Asian Law Caucus in San Francisco. “But it’s such a nerve-racking process. It shouldn’t require community outrage and rallies to get ICE to step in and do the basic, humane thing.”

Prasad said the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation has a policy of notifying incarcerated people if an immigration detainer is dropped, but that didn’t happen here. Even in recent weeks, Yung’s CDCR counselor had told him the hold was still on file, Prasad said.

Through his sister, Yung said he won’t feel confident that ICE isn’t going to detain him until he sees it in writing.

Immigrants funneled from prison to ICE detention

The state prison system hands over hundreds of inmates to ICE each year. Between Jan. 1, 2020, and Nov. 30, 2021, the CDCR made 2,600 transfers to ICE, according to data obtained from the agency by the Asian Law Caucus.

And advocates say Yung’s case highlights an injustice: If he had been born in the U.S. or had become a naturalized U.S. citizen, then when he completed his sentence that would have settled his debt to society and he would go free. But as a lawful permanent resident, or “green card” holder, his felony record meant he could be deported.

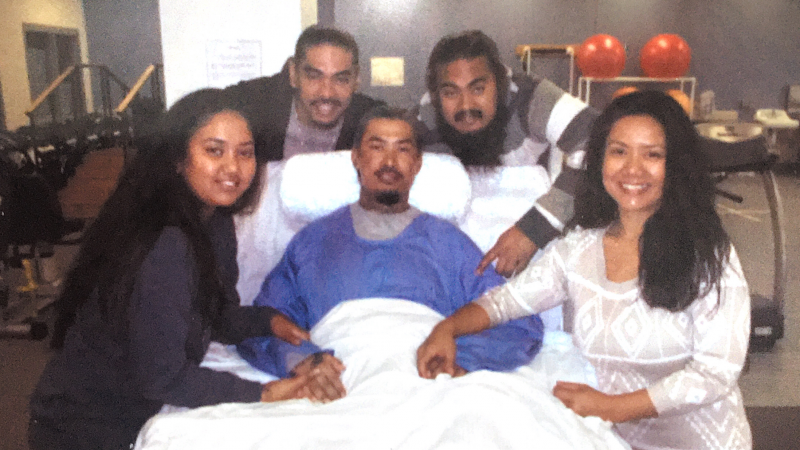

Yung’s sister Terry Honoré said she was terrified at the thought that her quadriplegic brother could be sent to Cambodia to fend for himself.

“I just don’t know how that would work,” she said. “It was really scary.”

Advocates also feared that Yung’s health could deteriorate in immigration detention, since ICE has been sued over inadequate care for people with disabilities.

“The level of medical neglect at baseline in ICE facilities is horrific,” said Prasad.

He added that given how seriously injured Yung is, there’s no plausible argument he could pose a danger to society.

The Asian Prisoner Support Committee and other advocacy groups are pushing for passage of the Vision Act, a bill in the state Senate that would block jail and prison officials from honoring ICE detainers for most inmates, like Yung, when they’re released.

Scores of people turned out for the Los Angeles rally Friday to push for that bill, AB 937, and support Yung.

Gov. Gavin Newsom has until April 12 to review Yung’s parole. Unless he moves to block it, Yung will be released from prison and paroled to the care of his family. But advocates want Newsom to go further and stop transfers from California prisons to ICE.

In a statement, CDCR press secretary Dana Simas said the prison system notifies ICE of anyone they’re holding who might be a foreign national. ICE then determines their immigration status and decides whether to put an immigration “hold” or detainer on the person.