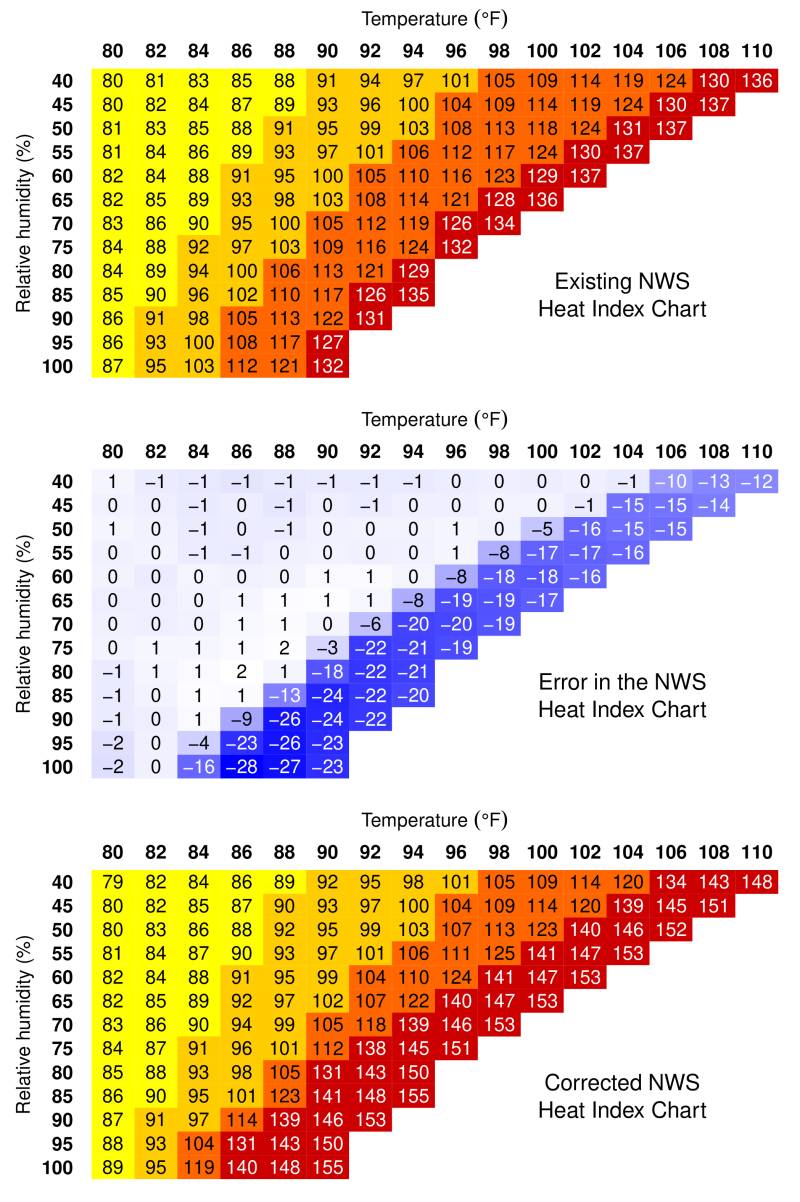

They found the National Weather Service’s current heat index is underestimating the effect of high heat by as much as 28 degrees. One example: in the 1995 Chicago heat wave, the heat index at the time showed the temperature and humidity felt like 124 degrees. Romps says using a corrected heat index, conditions actually felt like 141 degrees, putting the human body under an immense amount of cardiovascular stress.

“Using the correct heat index would allow us to identify those handful of times where the heat is so severe that it is pushing our bodies close to the breaking point,” Romps says. “What’s so important about it is that we can identify the times where the warnings really need to be made with clarity, and people really need to pay attention.”

The National Weather Service says it’s currently reviewing the results of Romps’ research.

“We’re trying to always learn more and take into consideration how we can improve not just our communication on heat, but how we can improve the different heat stress indicators,” McMahon says. “So we are working with the CDC, EPA and as well as many other of our federal partners to continue to try to find better and more widespread ways of alerting the general public, our emergency managers and our decision makers.”

Convincing the public that heat is more than a nuisance

For many, heat is all too common in the summertime and seems like more of a nuisance than a real danger. But climate change is making heat waves hotter, longer and more frequent.

“These are outside of people’s envelope of experience and they don’t expect them,” says Ann Bostrom, professor of environmental policy at the University of Washington. “So in those kinds of contexts, it’s very difficult for people, understandably, to understand the risks they’re exposed to.”

In addition to the heat index, the National Weather Service releases an “excessive heat warning” when a heat wave gets dangerous. But critics say that language is too general and not specific enough for vulnerable groups.

“There is a big difference between knowing it’s hot and knowing what I need to do individually,” Ebi says. “We do need to work better on the messaging.”

The weather service is piloting a new kind of heat alert in the Western U.S., known as HeatRisk. It provides heat alerts at four different levels, with specific warnings for who is at risk. It also takes into account how long a heat wave has been going on, as well as whether people are enduring high nighttime temperatures, giving them little respite.

Last week, California also approved a first-of-kind bill that requires the state to develop a heat wave ranking system, which will establish warnings based on the health impacts of heat on vulnerable populations.

Disaster experts say even the most targeted messages aren’t useful unless they’re actually reaching people. A key step is working with local groups to reach vulnerable populations, like senior centers, neighborhood groups or church groups.

As temperatures keep rising, even cities that aren’t known for blistering summers will need to begin that kind of planning.

“It’s not just the hottest cities that need to be addressing heat,” says Sara Meerow, associate professor at Arizona State University who works on heat. “Communities everywhere do. Places that have not had to worry as much about excessive heat need to now.”

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))