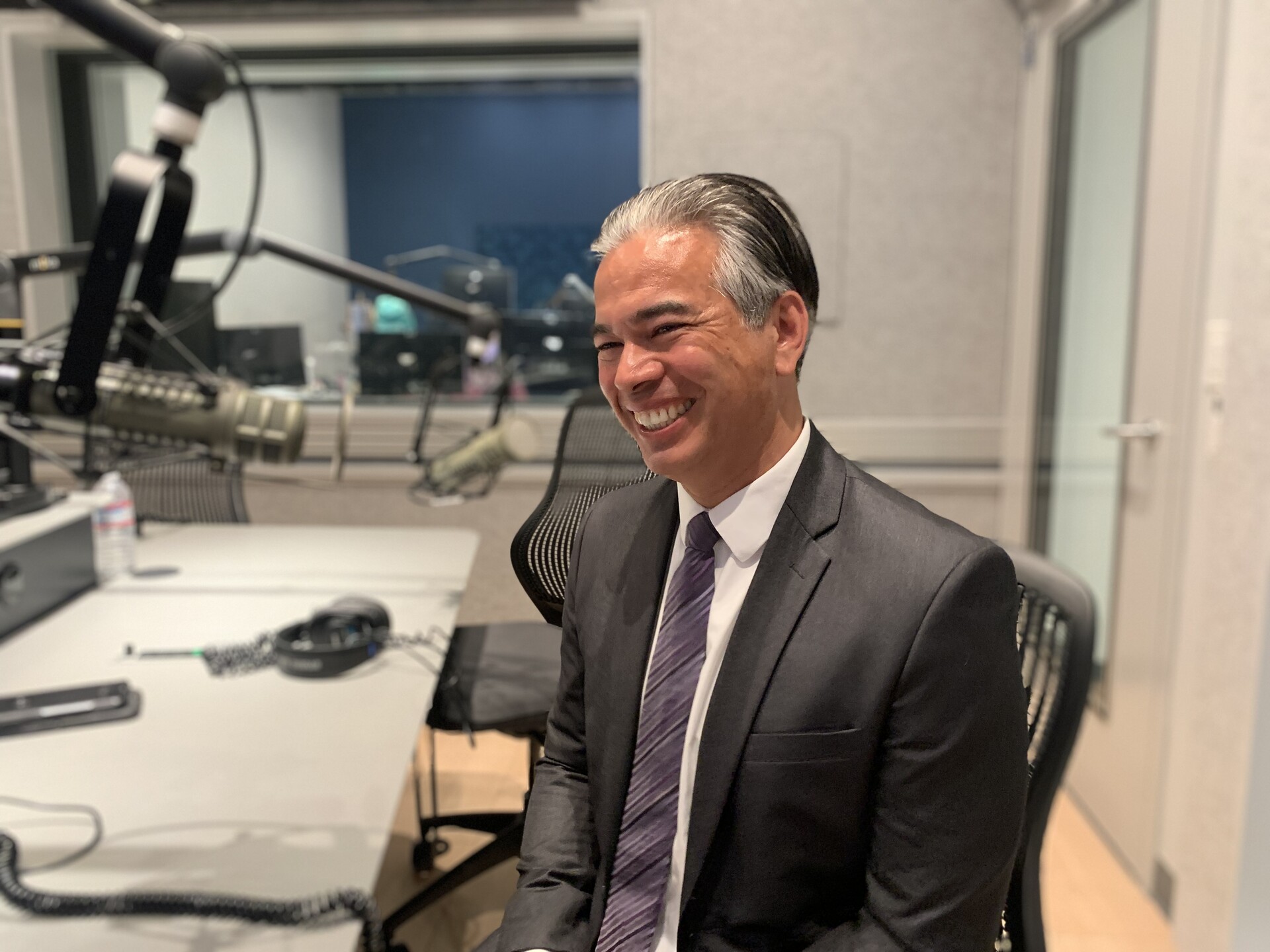

Though prior attorneys general in California have enforced housing laws, none has done so quite so deliberately or aggressively as Bonta. He credited his experience as a legislator in the housing-constrained Bay Area and said that his office is simply responding to the escalating severity of the affordable-housing crisis.

“We wanted to put a stake in the ground, to send a message to the state that there are laws in the state of California that are not optional. They must be followed, including by other governments, including cities and counties, who shouldn’t be calling themselves, wrongfully, mountain lion sanctuaries to escape the law,” said Bonta, in reference to the city of Woodside.

“People say, ‘I never thought of the AG as someone who could be involved in housing,’” he said. “We enforce all laws, not just criminal laws, but also civil laws, including housing laws.”

2. Redefining ‘violent crime’

In 2016, California voters passed Proposition 57 to make it easier for incarcerated people who committed nonviolent crimes to apply for early release.

But the law defined “violent” felonies with just 23 offenses. Missing from that list are domestic violence, human trafficking and certain types of assault and rape.

Conservatives have been using those omissions as a cudgel to beat “criminal justice reform”-aligned Democrats ever since. In the past, Bonta has hinted at possible tweaks to the law that he would support.

In the CalMatters interview, he was more explicit: “Domestic violence, human trafficking, rape of an unconscious person, all of those should be discussed, and potentially changed.”

3. Death penalty and cash bail, reconsidered

Unlike Hochman, Bonta has a lengthy political record as a legislator. And it’s a telling one.

In 2018, he co-authored a bill to ban county courts from setting cash bail for people awaiting trial, instead leaving the decision about whether a person should go free or not to a judge using “risk-assessment tools.” That bill was signed into law. But voters nixed that idea in a 2020 referendum funded by the bail bond industry.

That public rebuke hasn’t changed Bonta’s mind. He argued that voters may have been wary of the risk-assessment system that would have replaced the current system, which he acknowledged was “not perfect.”

But cash bail, he insisted, remains unpopular — and manifestly unfair.

“I believe that the current bail system punishes poor people for being poor, makes the jailhouse door swing open and closed based on how much money you have in your pocket, and judges you based on the size of your wallet, instead of the size of your risk,” he said.

While in the Assembly, Bonta also supported a proposed constitutional amendment to officially end the death penalty in California. That’s despite the fact that California voters have repeatedly turned down that opportunity, including as recently as 2016. California hasn’t executed a prisoner since 2006, and in 2019 Newsom declared a moratorium on the practice.

Bonta said that if a capital punishment ban were to return to the ballot, he would support it. But he also stressed that, for now, his personal views do not trump current law.

4. Playing a ‘dangerous game,’ but ‘responsibly’

Last year, before the U.S. Supreme Court ended the federal constitutional right to an abortion entirely in June, Texas lawmakers came up with a clever way to effectively ban most abortions in the state.

Rather than have law enforcement enforce the restriction on ending a pregnancy after six weeks, a state law gave individual Texans the right to sue health care providers, patients or anyone who “aided and abetted” an abortion, with the potential promise of a $10,000 bounty per violation. Because the state wasn’t enforcing the policy, the law was harder to challenge in court.

After the Supreme Court let the Texas law stand, Newsom clapped back, proposing a similarly structured bounty bill aimed at those who violate certain California gun laws. Bonta, whose office vociferously opposed the Texas law, helped craft the California version and was one of its most vocal public champions.

Reporters and commentators have described the California rejoinder as “trolling,” a “legislative stunt” and a blue state’s “taunt” of a conservative Supreme Court.

Bonta insisted that the law is an earnest effort to “save lives,” but also acknowledged that it was meant to call the high court’s bluff.

“We’re using it in the best way that it can be used, in a way that advances California values,” he said. “But it’s dangerous. It’s a dangerous game. We’re using it responsibly. Now others can use it like Texas, and maybe the Supreme Court will look at the landscape of how this approach is being used and try to correct it. If that happens, that’s fine, too.”

5. Ready to try again on concealed carry

The most high-profile setback of Bonta’s tenure to date was the failure of a bill his office wrote that would have made it more difficult for Californians to apply for the right to carry concealed firearms and that would have placed new restrictions on where they can take those guns.

The failed proposal was a response to another controversial decision by the U.S. Supreme Court in June. This one barred states from requiring concealed carry applicants to prove that they have a compelling need. Bonta’s proposed legislative workaround would have instead introduced “objective” restrictions, such as a prolonged training course requirement and a psychological assessment. It also designated arenas and other public gathering places and most private businesses as gun-free “sensitive” places.

Despite arm-twisting by Bonta himself, the bill died in the final hours of the legislative session, the victim of law enforcement opposition, an overly confident legislative strategy and rifts within the Assembly’s Democratic ranks.

Bonta said his sense of urgency remains as acute as ever.

“There will be, and there have been, huge spikes in the number of applicants,” he said. “We believe that it’s important to have a constitutional regime that allows for those who should constitutionally have a concealed carry weapon to have (one), but to take the steps to make sure that we are doing everything constitutionally permissible to keep people safe.”

Bonta echoed comments made by the bill’s author, state Sen. Anthony Portantino, a Glendale Democrat, who said that he would like to see the bill, or some version of it, introduced as soon as the next session begins in December.

That plan hit a possible speed bump late last month. Where California’s bill failed, a similar proposal in New York was signed into law, only for a federal judge to rule this month that its long list of “sensitive places” is unconstitutional.

“So we need to look at that, and maybe it is over-broad,” Bonta said, “and we should take that to heart … and respond appropriately with any new (similar) bill.”