The first time Alyssa Ibarra tried to get suboxone, a medication proven to treat opioid use disorder, she bought it from someone off the street.

After an ankle injury in 2014, she started using Vicodin and Percocet recreationally and later developed an addiction to opioids after experiencing postpartum depression.

“When I tried to stop, I remember just feeling really hopeless,” Ibarra said. “I didn’t even think, ‘I’m having withdrawals.’ I just thought it was the postpartum.”

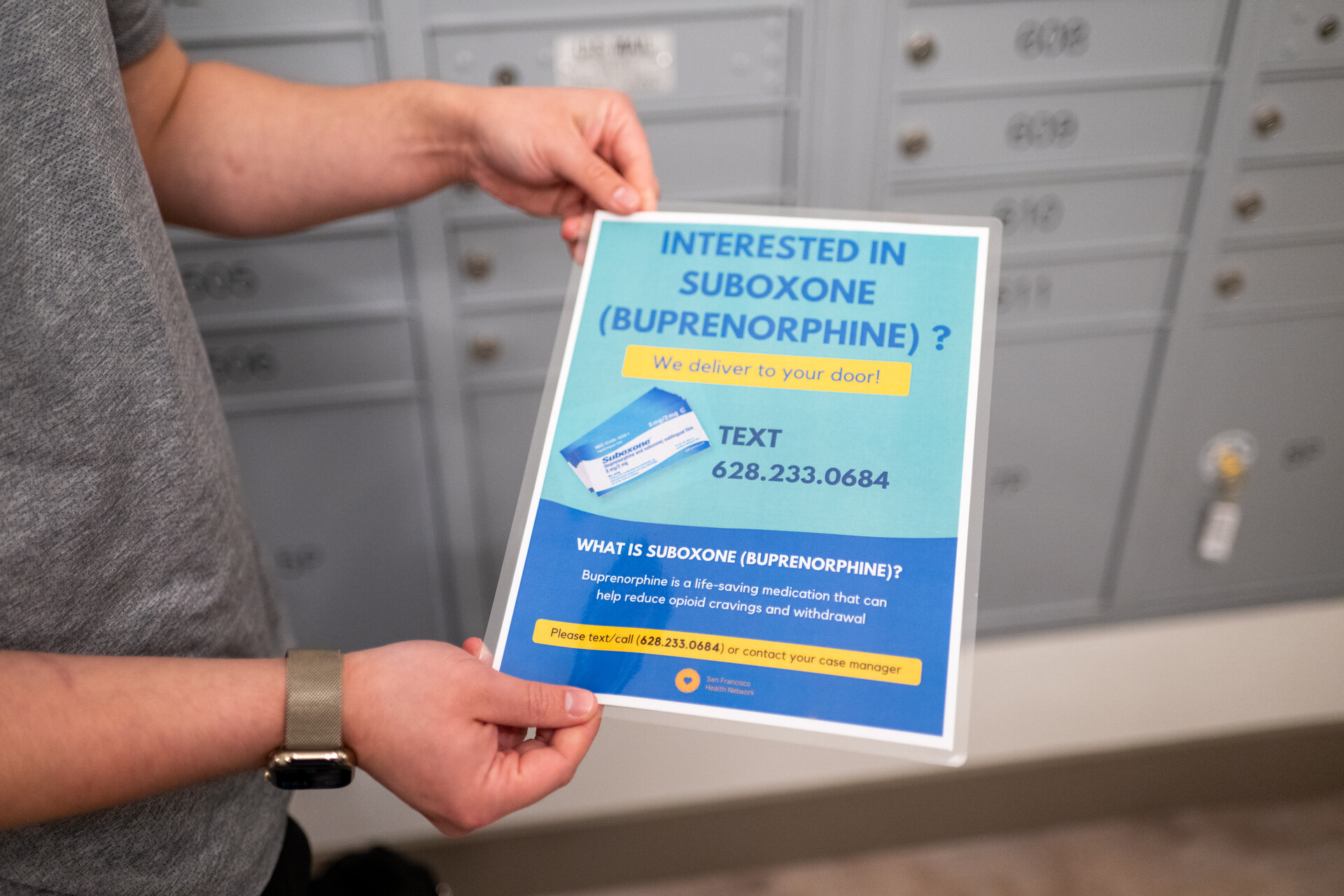

Until recently, medications for opioid use disorder, like methadone, suboxone or buprenorphine, a generic form of suboxone, have been so tightly regulated that only about 27% of Americans with opioid use disorder have been able to access medication-assisted treatment, according to a 2022 study by doctors at Rutgers and Columbia universities.

At the same time, overdose deaths have increased locally (PDF) and across the U.S., killing nearly 107,000 people nationally in 2021, largely driven by synthetic opioids such as fentanyl, which is up to 100 times more powerful than morphine.

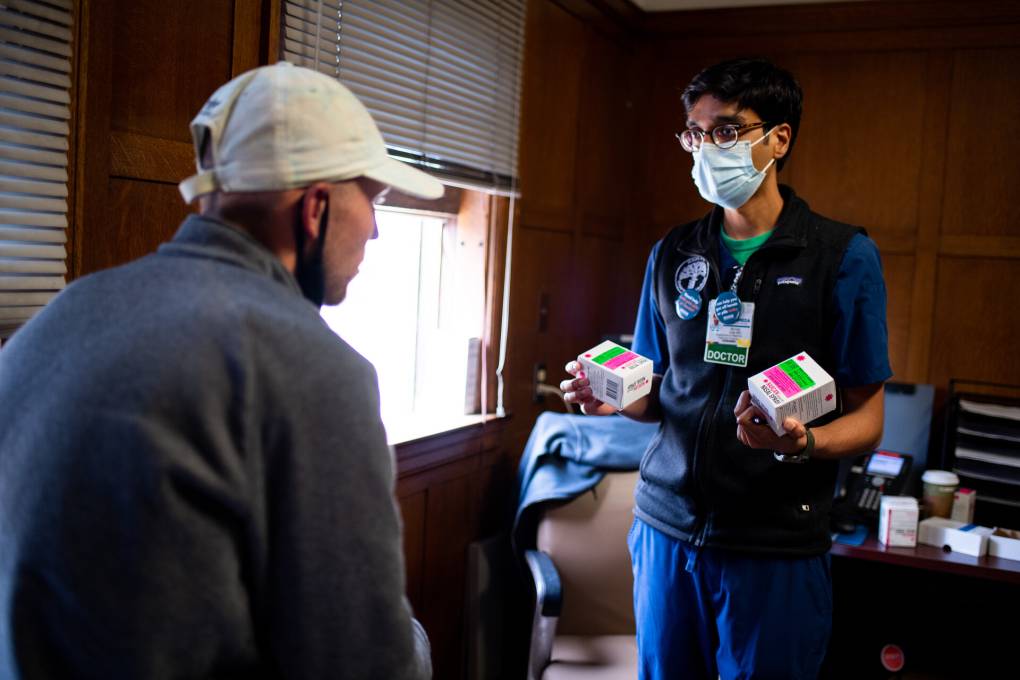

But local public health professionals and federal drug regulators are beginning to address the gap in access to medication-based treatment, so people like Ibarra can get the safe access they need faster.

“When someone needs it in the moment, they need it in that moment. They can’t wait months for an appointment,” said Dr. Christine Soran, medical director for San Francisco’s public Outpatient Buprenorphine Induction Clinic. “The city is putting resources behind it, and almost every medical provider I talk to is on board with this kind of treatment.”

In San Francisco, the number of people who receive buprenorphine has doubled since 2013, according to data from the Department of Public Health, with a 53% increase in the past five years. Ibarra is part of that group.