Read a transcript of this episode here.

To Rose Gelfand, Children’s Fairyland exists “outside of the bounds of time.”

Gelfand grew up in Richmond and as a kid went regularly to the 10-acre storybook-themed amusement park on the north side of Oakland’s Lake Merritt. But even as a teenager, when Gelfand attended high school at Oakland School for the Arts, Fairyland’s rainbow-colored sign remained a destination.

“Oftentimes I would meet friends at the Fairyland sign facing the water and sit in the sun and, you know, have long chats and make art together,” said Gelfand, who now lives in Portland, Oregon.

“[It] sort of always had this presence in our lives, even past the point where I was going as a kid.”

Gelfand is certainly not the only person who grew up in the Bay Area, or currently lives here, who considers Fairyland an iconic East Bay institution.

The park’s timeless charm may come from its elaborate play sets based on classic fairy tales — most of which were made in the 1950s and ’60s and have changed little since then.

But as the park approaches its 75th anniversary, in 2025, its leadership is pondering how to update it to better reflect Oakland’s ever-growing diversity.

Gelfand has been wondering something similar.

“I’m kind of curious what their plan is moving into the future and if it will continue to exist as it is,” she told KQED.

‘Kiddy tech’

If you’ve already been to Children’s Fairyland, you’ll know it’s nothing like a Disney theme park. There are no extravagant light shows, no giant castles and no Donald Duck mascots.

The park is a unique landscape of dozens of interactive play installations — ideal for kids 8 years old and under — to climb on or into or run through. The play sets are all based on popular kids’ stories: nursery rhymes like “Mary Had a Little Lamb,” classic children’s books like Peter Rabbit, and folktales like those about Johnny Appleseed and Anansi the Spider.

A “magic” key — bought for a few bucks — unlocks the story of each scene through a colorful speaker box next to each story station.

The park’s structures are kid-size and slightly crooked, as if they were sprinkled with a bit of surrealist fairy dust.

Everything looks vintage, which makes sense because of when most sets were built. Many of the play areas could use a coat of paint or even an extra nail. But the veneer of the play areas is not the point, says Randal Metz, who has worked at the park for more than 50 years. It’s about the imagination the spaces provoke, he says.

“Fairyland is a place for kids to lose themselves and to create their own fairytale fantasies,” said Metz, who was once the park’s artistic director, and is now a puppeteer and park historian.

Metz says the park’s style is intentionally “quiet” so that kids use their own creativity to add depth and detail to the stories through play.

“We’re low tech. We call it kiddy tech. We like to keep it simple, and so that things turn and they move for the children. But also they can understand how it happens.”

Parks within parks

Children’s Fairyland was born out of Oakland’s post-World War II period. Young soldiers returning from war were starting families and wanted a place to escape, Metz writes in his book Creating a Fairyland, which he co-authored with Tony Jonick. At the same time, a landscape architect named William Penn Mott Jr. became the Oakland parks superintendent, with grand visions for expanding the city’s public green spaces.

“There were approximately 950 acres of Oakland city parks in 1946, which was really low for a city of Oakland’s population and size,” said Mitchell Schwarzer, professor emeritus at California College of the Arts, and author of Hella Town: Oakland’s History of Development and Disruption.

“Mott wanted to build more, and he came up with all these ideas to increase the acreage of the park system,” Schwarzer said.

But Mott hit some roadblocks. He couldn’t create new parks because Oakland taxpayers didn’t have an appetite to pay more for them, according to Schwarzer, and Mott’s other idea, to create a fantasy-themed park for teenagers — with a mini train, boat and auto course — failed.

“He had a kind of crisis of spirit in the late ’40s and thought, ‘Well, I’ve got to go a different direction,’” said Schwarzer.

His new approach? Create parks within parks.

“If you can’t have lots of space, you can create space in people’s minds,” said Schwarzer.

But Mott didn’t launch Fairyland on his own. In fact, the idea to create the park was fueled by Arthur Navlet, a local business investor who had run a large plant nursery in Oakland.

Navlet and his wife had no children, but still had a deep love for children, according to Metz. While in retirement, the couple visited a children’s zoo in Detroit and were inspired by the bright colors and “festive” environment for the animals, who were not confined to the industrial cages that were customary at the time. Navlet came back to the East Bay determined to create something similar in Oakland.

Navlet was a member of the Lake Merritt Breakfast Club, a civic-minded group of businessmen who were interested in development. He drummed up their support and, along with Mott, raised seed money to develop a plan for the new park.

They hired local artist and industrial designer William Russell Everett, who sketched out the first 17 sets of the park.

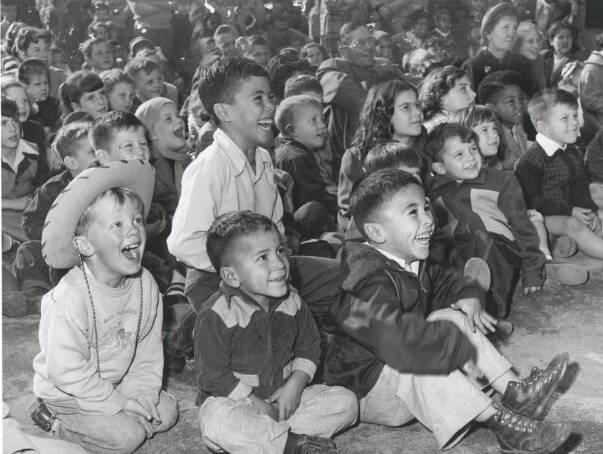

Children’s Fairyland officially opened in September 1950, presenting stories such as The Little Red Hen and Three Billy Goats Gruff, and the story of Noah’s ark, to nearly half a million people in the first year of operation.

Fairyland soon inspired other cities, like Sacramento, to open their own children’s storybook parks. Metz says Walt Disney himself visited the park and was deeply inspired by it when he opened Disneyland in 1955.

The Walt Disney Company says there’s no concrete evidence of Disney’s visit to the park, but records show that he did fly to San Francisco in 1954.

The company also went on to hire Fairyland’s first executive director, Dorothy Manes, to head up youth activities for Disneyland in the 1950s, according to former Disney archivist Dave Smith.

Children’s Fairyland started as a public park, and is now an independent nonprofit, operating with the financial help of memberships, donations and $16 entrance fees. It has endured over the decades, much like the timeless stories it recounts, says Schwarzer.

“This is one of Oakland’s most innovative and lasting contributions to the whole country,” he said, about Fairyland’s ability to inspire other fantasy-themed storybook parks.

Scott Lukas, a cultural anthropologist and author of the book Theme Park, says Fairyland incorporates stories, fostering play and creativity, in a way that is pretty distinct from most other kids’ entertainment nowadays.

In contrast to Fairyland, “they’re not maybe being used for imagination and development of important skills in children, but they’re being used as properties, as brands, as commodities,” Lukas said.

And, he says, Fairyland is not trying to sell you anything or tell you what to think.