For the first time in state history, child care centers in California had to test their drinking water for possible lead contamination, and preliminary results show about a quarter of those that reported results contained unsafe levels of lead, according to data recently reported by state regulators.

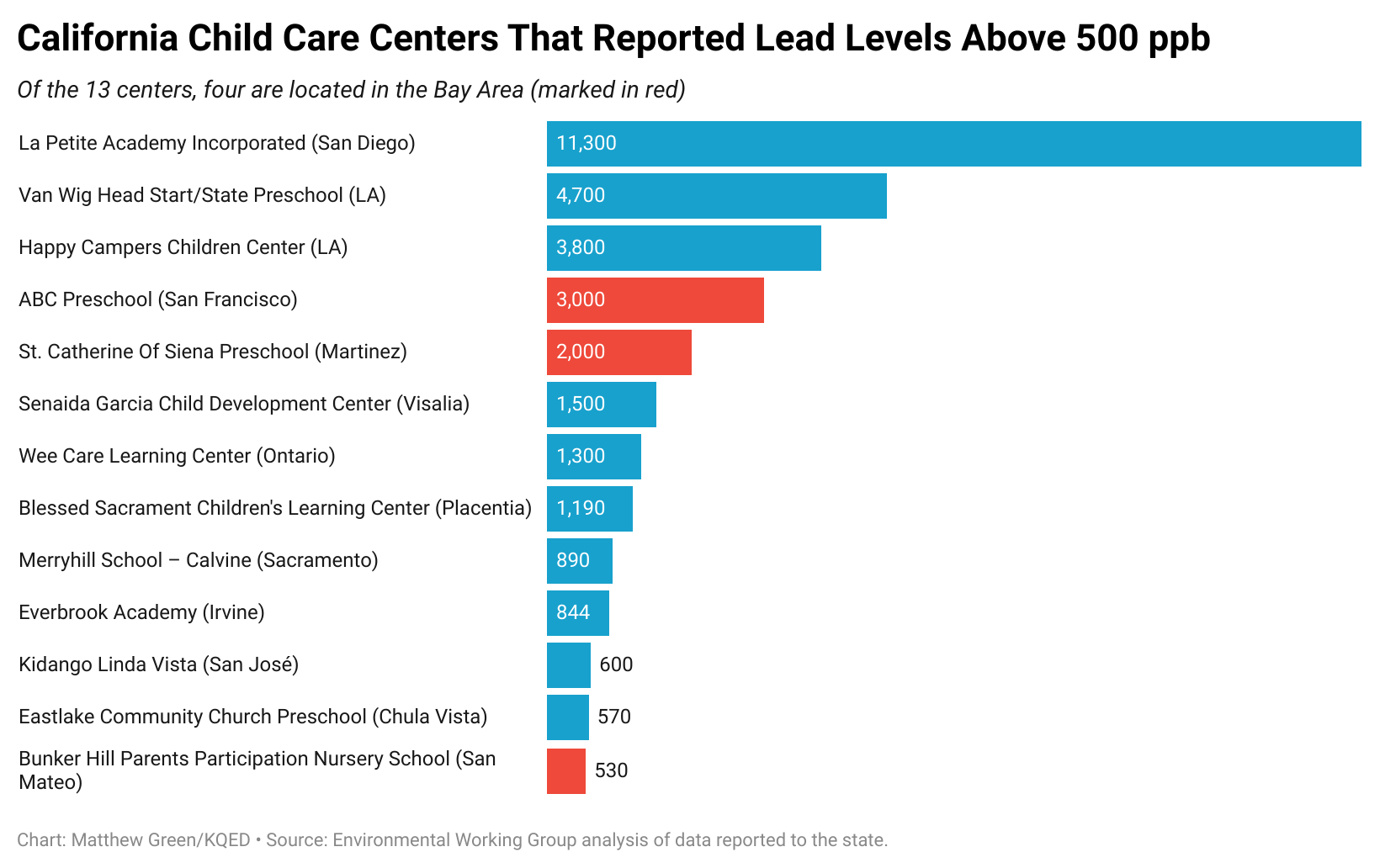

Of the nearly 6,900 centers whose results have been disclosed, almost 1,700 had lead levels that exceeded 5 parts per billion (ppb) — the state’s allowable limit for child care centers. Of those, 13 had lead levels above 500 ppb, including four in the Bay Area.

La Petite Academy in San Diego reported the highest levels of lead — 11,300 ppb — of any child care center in the state. That’s more than 2,200 times higher than what California allows, and comes close to some of the highest levels detected during the catastrophic water crisis in Flint, Michigan, nearly a decade ago.

The facility has since gotten rid of two drinking fountains with the highest lead samples and found its remaining water sources safe after retesting them, said Joanna Cline, spokesperson for the center.