On June 19, 1865, two months after Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to end the Civil War, a Union general trotted into Galveston, Texas, to notify still-enslaved Black people that they were free.

Juneteenth Across the Bay: A Celebration of Heritage and Reflections on Injustice Past and Present

That was the beginning of Juneteenth — Black Independence Day, if you will. Juneteenth has been celebrated by Black people, many of whom are ancestors of enslaved Africans and Americans, for more than 150 years. And in 2021, President Biden made Juneteenth — June 19 — a federal holiday in the wake of nationwide protests over police killings of Black Americans. Federal observance of a day commemorating the emancipation of enslaved people should be a reminder that the United States continues to avert a true reckoning over the treatment of Black people. And instead of intentional policies to repair the harm caused by slavery and the systemic racism and discrimination that continues to emanate from more than two centuries of forced labor, most Americans get an extra day off of work.

But let’s not rain on a day when Black joy shines.

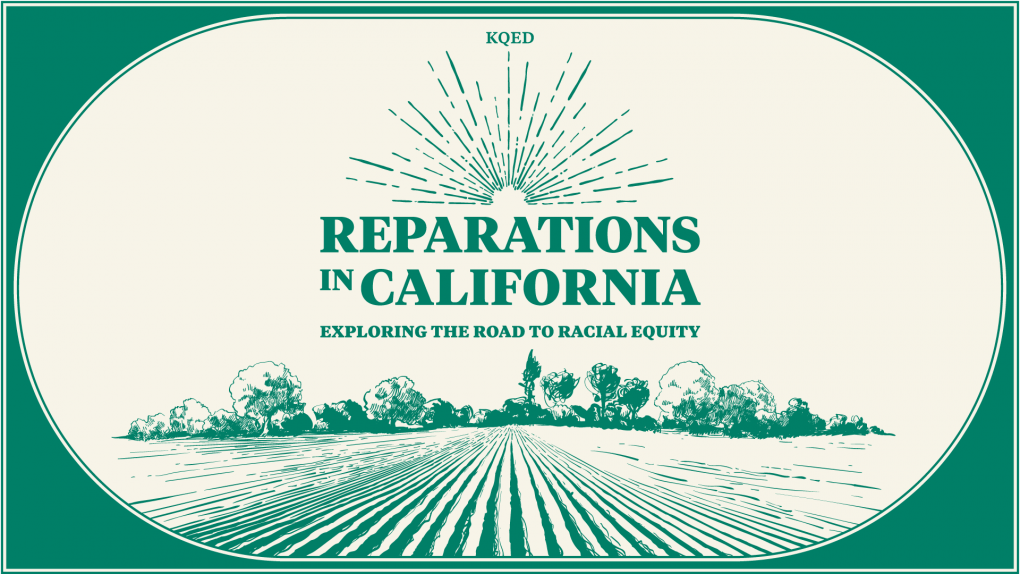

Juneteenth in Oakland, which held its 14th annual Juneteenth festival Saturday, is a family affair. Known as Fam Bam, the party honoring Black culture and held at Lake Merritt Amphitheater, was actually the kickoff of a weekend-long celebration.

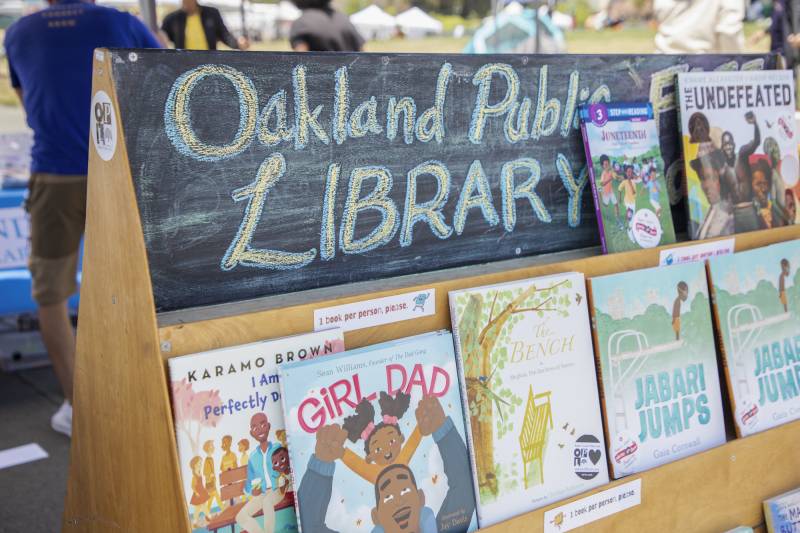

As people celebrate freedoms granted in the past, some are thinking about California’s ongoing reparations efforts.

For Oakland resident Michael Spender, reparations mean “more channels to economic wealth, more channels to health care, more channels to security, the things that we need to have a better life … There’s a lot of money that is passed down, but it never seems to get where it’s supposed to go.”

The California Reparations Task Force will submit final recommendations to the Legislature at the end of this month.

Proposals will include how Black residents should be compensated for enduring oppression, and will suggest measures to repair decades of discriminatory policies in housing, education, health care, criminal justice and other areas.

“It’s more than just monetary,” said Fam Bam attendee Tonda Jackson from Oakland. “[It’s] education, housing, jobs.”

People gathered in cities across the Bay Area, including at Grace Bible Fellowship of Antioch for a Juneteenth celebration hosted by Grace Arms of Antioch, where there were bouncy houses, music and poetry performances, and wellness stations offering first aid and prayers.

Writer, poet and Antioch resident Ari Why said Juneteenth was open to everybody who’s ever been impoverished and “brought down by the system.”

“If you look into the history, African Americans are the only ones that haven’t received reparations for what they went through,” said Why, who also shared a poem on stage. “Every other nationality actually was paid off. Even white Americans were paid off … Slave owners that lost slaves got reparations.”

“Our country seems to be in denial about slavery. They don’t want to talk about things,” said Carrie Frazier, executive director for Village Keepers, a nonprofit that supports Black families affected by poverty and systemic racism in East and Central Contra Costa County. “So for us to be able to know that our history is valid, it happened, and there was legislation to make it be freedom is important for us to know, because if we wait for the schools to teach it, we may never hear anything.”

KQED’s Otis R. Taylor Jr., María Fernanda Bernal, Billy Cruz, Amaya Edwards, Lakshmi Sarah and Attila Pelit contributed to this story.