She was San José’s first Latina city council member, and the first Latina on the Santa Clara County Board of Supervisors. Today, she goes by many honorifics, but Blanca Alvarado’s favorite is “La Madrina” — the godmother.

At 92 years old, her body has slowed down, and her hair has gone gray, but she remembers with absolute clarity the way her life tracked the rise of Chicana power in what we now call Silicon Valley. Born in Colorado, Alvarado came to San José with her family in 1948, when she was just 16 years old.

“San José had a population of 70,000 people,” she recalled. “So it was a small burg, you know?”

During that time, the region was called the Valley of Heart’s Delight, famous across the country for its stone fruit and vegetables. People from all over North America arrived in successive waves to pick and process the crops.

“The fragrance that wafted in the air — to this day, I will never, never forget it,” said Alvarado. “The valley was just replete with blossoms. All of the orchards were fruit orchards primarily.”

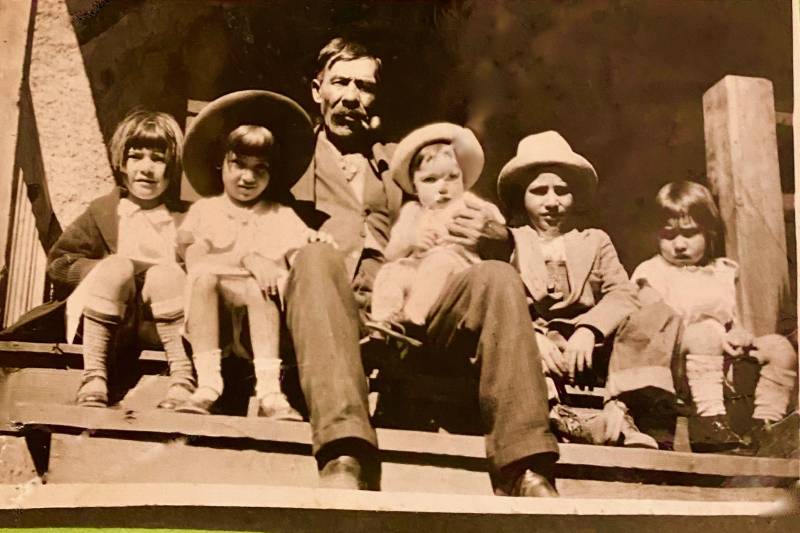

She remembers her father telling her that she was the best fruit picker in the family, but it was an incredibly difficult job. “Being on your knees, on clods of dirt. It was very uncomfortable, to say the least,” she said.

Alvarado’s life closely parallels the South Bay’s most famous Chicano export. César Chávez also moved here with his family in 1948. At one point, as a young man, he would work in an apricot orchard like Alvarado, making less than a dollar an hour.

“We lived in tents for two years. We lived in tin shacks for two years. Until finally, we were able to rent a house up in the foothills of Evergreen,” she said, referring to the neighborhood in East San José.

Successive waves of migration

Given the name, it’s obvious San José was founded by Latinos; on Nov. 29, 1777, as the Pueblo de San José de Guadalupe, to be specific. But it wasn’t until after the Civil War, when railroads crisscrossed North America, linking farmers and ranchers to millions of hungry consumers, that Mexicans began traveling north of the border to work on farms and ranches in the Western U.S.

“The railroads are definitely a sign of industrialization, and they’re used not only to bring fruit out to markets, but bring labor in,” said Dr. Margo McBane, history professor and co-director of an extensive oral history project based at San José State called Before Silicon Valley: A History of Mexican Agricultural and Cannery Workers of Santa Clara County, 1920–1960.