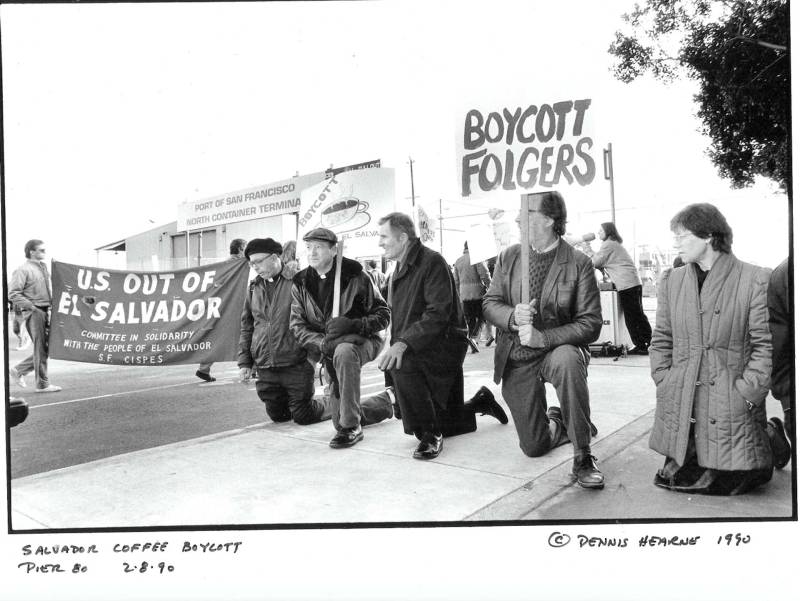

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: I’m Ericka Cruz Guevarra, and Welcome to the Bay. Local News to Keep You Rooted. One day in February of 1990, about 100 protesters gathered at Pier 96 in San Francisco’s Bayview neighborhood. They came to stop precious cargo from moving for the San Francisco ports, coffee beans from El Salvador. For the activists, those coffee beans were the moneymaking engine behind a brutal civil war going on in El Salvador. And if San Francisco’s big coffee companies were buying up those beans, they thought they were effectively funding a civil war, too.

Monika Trobits: They argue that El Salvador $400 million worth of annual coffee exports mainly benefited a handful of families in El Salvador, which was in turn financing the military atrocities against the local civilians there.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: Despite the Bay Area’s iconic history of activism, the history of Salvadorians and port workers throughout the eighties and nineties is a lesser known story. So today we’re going to talk with reporter Sebastian Miño-Bucheli about how these efforts by Bay Area activists would eventually help end a war. Stay with us.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: So I spoke with Felix.

Felix Kury: Felix Kury.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: He’s a retired lecturer who taught mental health classes at State for 30 years in Latino Latino Studies Department. He was born in San Francisco but went back to El Salvador. And it was in that time that there was this repression going on because of a military dictatorship that had been ongoing since the 1930s in 1932.

Felix Kury: Right. There were about 30,000 people that were killed.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: He tells me that, you know, the repression is so bad that if you were from a different class, you couldn’t walk on a certain street without getting harassed by the military or the police.

Felix Kury: We understood and we knew that the military controlled the state. And behind them they were pure in their right to the oligarchs. They controlled absolutely everything.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: He went through all of this basically, and came to a time where he went back to the United States.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: So he was here in the United States as a student. He was going to school in San Francisco. But he was also very much aware of what was happening in El Salvador. How did he describe what it was like to be a student during that time? And what were some of the things that were like on his mind?

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: So he and other Salvadorans were following the news back home. They were constantly checking to see if something had happened, if their family members were okay. This is a time period where, you know, if you spoke out against the government, you disappeared.

Felix Kury: What it was really important for many of us of my generation, is the massacre of 1975 in El Salvador of university student. And that’s how we began to organize. And we met, you know, with oil companeros and and also Salvadorians, and decided that we needed to do that.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: Even got to the point where they even occupied the Salvadoran consulate here in San Francisco just to raise awareness about what was going on.

Felix Kury: To stop the war, to stop doing the repression.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: And was there a moment in particular where he was like, Whoa, this is really, really bad?

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: That was really the assassination of Monsignor Oscar Romero. He was an archbishop in El Salvador.

Felix Kury: And he was the spiritual advisor of my school. And I will see him all the time when I was in Selma, Ala. And so I will go to confession to him and all of that.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: He was telling me all of this in his living room where there was a a portrait of Archbishop Romero.

Felix Kury: You know, Archbishop Romero began to talk about what was happening until now, what didn’t matter, the unknown. They were they probably said later, we all share this and no matter.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: The archbishop was assassinated tearing homily. He’s denouncing the government and the repression that someone went up and assassinated the archbishop.

Felix Kury: The murderer of the of the bishop gave a signal for many of us that no one would be safe.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: I spoke to him on the day that the anniversary had happened where he was assassinated. And so it was this like heavy moment for both of us. We’re like, I’m sorry, we’re living through this trauma. Other Salvadorans can tell you this, that it was very detrimental to to them.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: And it also was a moment that sort of began to kick off what would become a civil war in El Salvador, right?

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: Yeah.

Felix Kury: And then all of us began to say, what do we do? You know, what do we do? We have to go beyond working with Salvadorians to develop a movement.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: Felix Khoury joined other like minded people to form the Eastbay Interfaith Task Force on El Salvador in November of 1980. This group teamed up with port workers to stop the U.S. government from shipping weapons and tanks from the Port of Oakland. This action spread up and down the West Coast. This blockade also set the stage for another protest action that tried to hit the Salvadoran government where it would hurt the most. Its coffee industry, which at the time was really important to San Francisco to.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: Here in San Francisco, you have the big three coffee companies along with Hill’s brothers and MJB, which was founded in San Francisco in the late 19th century. A lot of coffee that was coming from Latin America was being offloaded in San Francisco or, you know, in the Bay Area. From here. I would just go on to the East Coast, to Southwest, etc..

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: So it was a big deal in San Francisco. But how big of a deal was coffee for a country like El Salvador at the time? Like what was the connection that people were making between coffee and the war?

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: So like the way that El Salvador was able to generate income around this time was that the country itself became a monoculture of coffee, that people who are benefiting from this, they were called the 14th families. They were these rich landowners, but they also had their hand in politics and also the military. So we can also say that they’re oligarchs. By just funding coffee, you are also helping the Salvadoran government and military regime. So that’s like one thing to keep in mind. Like when people were trying to target Salvadorian coffee, it was because they wanted to hurt the pockets of the 14 families.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: One of the most important groups that led these coffee protests was called Neighbor to Neighbor, and it was led by a labor organizer from San Francisco named Fred Ross Jr. Their goal was to stop U.S. aid to Nicaragua and El Salvador, and they had members all over the country. How do these activists begin to impact the coffee industry? Like, what did that look like exactly for these activists in the Bay Area?

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: So it really began with like TV spots.

Commercial Your tax dollars are putting America into the red, the red of El Salvador. $4 billion in ten years.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: Where they were just trying to raise awareness that as Americans, we should stop drinking coffee that comes from El Salvador. Those ads never really got to air because they were considered too violent.

News Anchor: With four w mtw is not alone. No network affiliate in the Portland area will run the ad for.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: They show just brutal images from the war. They show like a coffee cup that has blood spilling out of it. And so that was one of the ways that they were trying to do this.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: So neighbor to neighbor began organizing. But things I know really picked up in 1990. Can you tell me about what happened in 1990?

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: Around 60% of Salvadoran coffee harvests were being shipped to United States. And it was at that time it was like the biggest buyer, the market.

Monika Trobits: And what happened was you had a little war going on down there.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: Monika Trobits is a historian and author Bay Area Coffee.

Monika Trobits: And what they wanted the dockworkers to do was not unload any ship, any freighter coming in from El Salvador carrying all these coffee beans, just flat out, don’t do it. And one fine day in February of 1990, one of those freighter sales it with 34 tons of Salvadorian coffee beans. That is a lot of coffee beans.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: They set up picket lines to stop Salvadorian coffee.

Monika Trobits: And it is met by neighbor to neighbor protesters, about 100 of them marching back and forth along the dock and longshoreman.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: They did not want to cross the picket line. So they also joined in on the effort to stop the offloading of Salvadorian coffee.

Monika Trobits: The freighter was now being unloaded. So the captain decided to move on.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: They were able to stop this cargo ship from undocking all over the West Coast.

Monika Trobits: Sailed up to Vancouver near Canada, met the same kind of resistance, went down to Seattle, same thing happened. Headed down to Long Beach. Exact same thing happened.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: The captain of the ship that went over into the said, We’re going to have to just go back home. We can’t dock anywhere and offload our coffee.

Monika Trobits: So in the end, this freighter had every one of those beans, ended up going back to El Salvador.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: So I know this protest spread from San Francisco up and down the West Coast. How long did it ultimately last?

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: This boycott lasted two years while it was going on. The San Francisco Board of Supervisors voted to boycott Salvadoran coffee beans. The California state legislature formally protested human rights violations against civilians by the Salvadoran military. They were neighbor, really did their job.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: And how about El Salvador? I mean, what impact did these protests end up having there?

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: A series of events where you had a grandson from The Gamble family, from Procter and Gamble.

Monika Trobits: Folgers by this point was owned by Procter and Gamble.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: They were trying to raise awareness that, you know, we got to stop buying coffee from El Salvador. We got to do something. We can’t continue on with this boycott. The fear of a boycott happening to a company, in essence, is enough to scare the company, to just follow through with the message that people want. Procter Gamble, Nestlé and Kraft took out ads in the Salvadoran newspaper urging the government to negotiate a peace settlement.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: And so when did a peace settlement ultimately happen?

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: So it happened between that like New Year’s Eve of 1991, 1992, when it was formally signed. Two months later, they were neighbors saw that this was a win and they just stopped the boycott.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: The story is really cool and like amazing to see just such a cross-section of people coming together in this effort that really originated here in the Bay Area and then had such a big impact in another country.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: I initially read this book on Bay Area History and Coffee, and one thing I really loved about it was like this, this solidarity to come together. You have, you know, people who are being displaced from the country because of war. They’re coming together to help others in their time of need. You have a collaboration between two unions. They want to help each other. And then you also hearing from the people and what they’re going through. Like, these are real people telling me what they were feeling back in the eighties and the early nineties, and I really wanted to tell their story. So it’s more reflected in the history that we know today.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: Yeah. And I was just thinking, too. I mean, I grew up here in the Bay Area and we are known for like these really cool and amazing just moments in our history of activism. But this is like, not quite a story that I was actually aware of. And I wonder if, like, it was like an overlooked sort of part of our history of activism here.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: I didn’t grow up here in the Bay, and I’ve heard about these, like you said, like grand stories of of activism. I really wish that this was a part of that, too, now.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: And I guess it is. Yeah, reporting on it. Well, Sebastian, thank you so much for sharing your reporting with us. It was really fun talking with you.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: Thanks for having me on the day. It was great. Speak with you.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: That was Sebastian Miño-Bucheli, a reporter for KQED. This conversation with Sebastian was cut down and edited by our senior editor, Alan Montecillo. Producer Maria Esquinca pitched this episode, scored it and added all the tape. Extra production support from me. Shout out to the rest of the podcast squad here at KQED. That’s Jen Chien, director of Podcasts. Katie Sprenger, Podcast Operations Manager, Audience Engagement Support from César Saldaña, and Holly Kernan is our chief content officer. The Bay is a production of member supported people powered KQED. I’m Ericka Cruz Guevarra. Talk to you next week.