Episode Transcript

This is a computer-generated transcript. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Olivia Allen-Price: 128 years ago, San Francisco was haunted by a bizarre, brutal murder case. A mild-mannered, upstanding “gentleman” was suspected of killing two young women who knew and trusted him. And to make matters worse, it happened inside one of the city’s revered churches.

[Church bell ringing]

Olivia Allen-Price: The suspect came to be known as “The Demon of the Belfry.” And in 1895, San Franciscans found themselves completely obsessed with this case.

[Theme music]

Olivia Allen-Price: If you ask someone living here now whether they know about “the Demon of the Belfry,” there’s a good chance they’ve never even heard of it. I was one of them.

This is Boo Curious. And we’ve made it to our final installment in the series. This week, we’re revisiting The Demon of the Belfry case to learn: What happened inside that church? What was it about these murders that possessed the city? And how did such an infamous case virtually disappear from the Bay Area’s memory? We’ll find out just ahead. I’m Olivia Allen-Price. Now, stay close. You don’t want to get lost.

[spooky laugh]

[church bell ringing]

Olivia Allen-Price: The Demon of the Belfry murders were the talk of the town in San Francisco around the turn of the century. Here to tell us the tale is KQED’s Carly Severn.

[music shift]

[sound of a busy cityscape, street cars]

Carly Severn: By 1895, San Francisco’s earlier life as a muddy, chaotic mining backwater was all but gone. This place was now a bustling, modern city staring down a new century. For almost 20 years, these streets had felt the hum of electricity and the rattle of cable cars. Seven by 7 miles packed with people — around 300,000 of them.

Back then, the Mission District was what was called a streetcar suburb, a place increasingly well-connected by mass transit to downtown and heavily inhabited by a working-class mix of immigrants, the majority at this time from Europe.

[sound of church bells]

Carly Severn: And in the middle of it all, on Bartlett Street, was the Emmanuel Baptist Church. A huge, imposing building. And on the very top, reaching into the sky above the Mission District, was the church’s bell tower — the belfry. And for several years in the 1890s, that dark, lonely belfry became the most dreaded space in San Francisco.

[church bells fade]

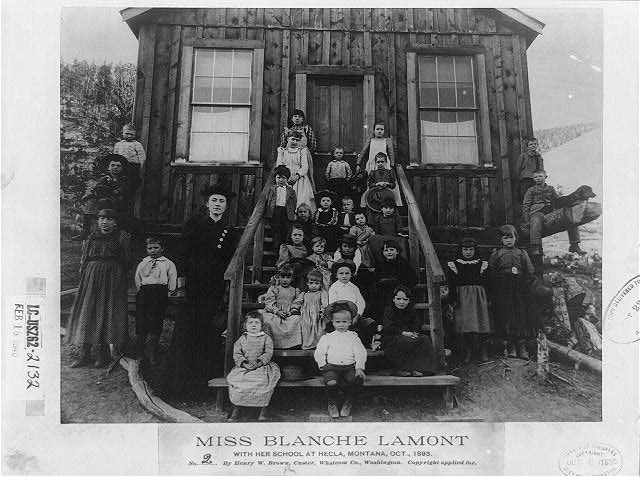

Here’s a short version of the case: A quiet, mild-mannered young medical student in his early twenties called Theo Durrant volunteered at the Sunday School. One afternoon in early April 1895, a young Mission District schoolteacher called Blanche Lamont was last seen with a friend of hers … Theo Durrant. When Blanche didn’t come home, Theo was questioned, but the police had no evidence of foul play.

[typing on a typewriter]

Voice reading a newspaper clipping: The police are utterly baffled. Blanche Lamont, a beautiful girl … has disappeared as mysteriously as if the earth had swallowed her.

Carly Severn: Nine days after Blanche disappeared, another young woman who attended the Emmanuel Baptist church — Minnie Williams — didn’t come home either. Like Blanche, she was last seen with Theo Durrant … walking into the church.

[typing on a typewriter]

Voice reading a newspaper clipping: Blanche Lamont and Minnie Williams were members of the Emmanuel Baptist church and members of the Sunday school class. Both were 21-year-old brunettes, pretty and modest girls.

[music]

Carly Severn: The morning after Minnie went missing, a volunteer opened one of the church closets … and found Minnie’s murdered body lying on the floor inside. And when police searched the rest of the building, the last place they looked was the very top: in the belfry.

[typing on a typewriter]

Voice reading a newspaper clipping: They broke in the door. It was so dark they could not see, and one of them struck a match. As the light flared, they saw before them the dead body of the girl for whom they were searching.

Carly Severn: The body of Blanche Lamont had been hidden up there for almost two weeks. Theo Durrant was immediately the prime suspect. And from the moment he was arrested, San Francisco’s mania for the “Demon of the Belfry” caught fire.

Virginia McConnell: There was the undercurrent of that, that this could happen in a church if it could happen in a church. It could happen anywhere. It could happen in your home.

[music ends]

Carly Severn: Writer Virginia McConnell used to practice law in San Francisco in the 1970s. When she moved into teaching, she also began digging into criminal histories of the past … and wound up writing a whole book on the Theo Durrant case. This murder trial had all the elements to mesmerize a willing city. It had a cast of young characters: well-spoken medical student Theo and the two attractive young women he stood accused of violently murdering with his bare hands. And this horrific double murder had taken place in a sacred space – the Emmanuel Baptist Church – which had then become these women’s tomb.

Virginia McConnell: That was the horror of, you know, is not the same as if, you know, you did it down at the local bar, but you did it in a church. So where was God now? Supposedly protecting his people. What happened to these two girls? That they could not be protected?

Carly Severn: Not only that, this reinforced all those fears that people living in a big, growing metropolis are susceptible to. That panic that their city was sinking into an unprecedented moral decay – an anxiety stoked by the newspapers that framed these crimes as the ultimate sign of San Francisco’s irredeemable rot.

[typing on a typewriter]

Voice reading a newspaper clipping: Casting reproach upon the already too low standard of morals in that city and a cloud of shame on the good name of our beautiful State.

[music begins]

Carly Severn: Then there was the breathless speculation about sex — scandalous, intriguing, salacious. Had Theo been romantically involved with either of the two women? Was this “gentleman,” in fact, a depraved pervert who’d habitually harassed and exposed his way through the Mission District, as was rumored?

Virginia McConnell: They still have these misconceptions that Theo was luring women into the church and exposing himself.

Carly Severn: And then there was Theo’s family. Rumors of an inappropriate closeness between Theo, his mother, and his sister spread like wildfire. It’s hard to convey just how all-consuming this case was in 1895. It dominated the news, swallowing up all the oxygen, and was covered far beyond San Francisco, all across the country.

[music ends]

Carly Severn: And as the evidence against him mounted up, Theo Durrant’s only hope was winning over the jury on the stand, which this oddly mannered young man truly failed to do. He constantly contradicted his own alibis and introduced new implausible theories about anyone else who could have murdered Blanche and Minnie rather than himself.

Virginia McConnell: He did not do himself any favors by getting on the stand, but they had no other …. They had no defense for him. They had no defense.

[sounds of people talking in a courtroom]

Carly Severn: And that’s the thing: this courtroom was packed. Because the Bay Area didn’t just indulge their fascination with this case through the papers. They also physically descended on the courtroom in person.

[typing on a typewriter]

Voice reading a newspaper clipping: So vivid were the stories, so graphic the pictures, so awful the scenes depicted that men and women leaned forward with straining eyes and hard-drawn breath, catching at every word, hypnotized by the horror of it.

Carly Severn: The major San Francisco newspapers, including the Chronicle, competed feverishly for who could attract the most readers with stories that were melodramatic, gossipy and crazy-readable. And as the trial progressed, the coverage became more lurid, more outlandish, and highly unethical. With reporters assigning themselves the kind of investigative role during the trial itself that you might more expect from the lawyers themselves or the police.

Virginia McConnell: Because they knew that [the] more sensational it was, the more information they could get. They could sell newspapers.

Carly Severn: One newspaper printed a dramatic story about Theo going on the run and terrorizing the city:

Virginia McConnell: They were going to arrest him, and he had escaped, and he was running through people’s backyards in the Mission district.

Carly Severn: It’s a great story! Except… it never happened.

Virginia McConnell: That whole thing was fake. That was false. The newspaper had nothing else to print.

Carly Severn: But the papers knew their readers wanted this. Humans have always wanted to gobble up true crime stories – whether in the daily paper back then or on our TV screens. Or increasingly, in our podcast feeds. Hello there. And as horribly new as this double murder seemed back in 1895, there was precedent for these kinds of famous killings.

Voice reading a newspaper clipping: The analogy with the murderous career of Jack the Ripper in London will at once suggest itself … Is the same bloody drama to be repeated in San Francisco?

Carly Severn: Just seven years before Theo went up to the belfry, the serial killer called “Jack the Ripper” terrorized another foggy city, London — in a saga that may have unfolded thousands of miles away but became a worldwide sensation thanks to the popular press. The trial of Lizzie Borden, accused of murdering her own father and stepmother with an ax in their Massachusetts home, had happened just three years before. Boston had even had its own Belfry Murderer 20 years earlier — dubbed “the Bat.” So, by 1895, there was a playbook for this stuff. And as horrible as it was, for many people, this was a distraction from the grind of daily life:

Virginia McConnell: This is entertainment. Think about what the entertainment was back then. Zippo. That’s what it was.

Carly Severn: But many onlookers in 1895 clearly had difficulty with the notion that a man could kill just for the sake of killing — not for profit or to satisfy depraved desires. Which is maybe why the worst legends about Theo Durrant were based around what he might have done to Blanche and Minnie’s bodies after their death — gruesome speculation about his “true” motive that endures to this day. It’s no coincidence that you’d have seen Theo compared to “Jekyll and Hyde” in the press — a book that was published not that long before the Belfry case but had already become an understood reference for a normal-looking exterior that concealed a fiendish, murdering alter-ego.

Virginia McConnell: It’s a way, I think, of coming to terms with people who seem to be good can do bad things.

Carly Severn: If the idea of what a criminal does — and doesn’t — “look like” is still recognizable today … then the idea of a “perfect victim” is unfortunately just as relevant. Even though Theo was charged with the murders of both Blanche and Minnie and Minnie’s killing was by far the more bloody, physically brutal one, the all-male prosecution team chose to only try him for the murder of Blanche.

Virginia McConnell: There was thinking in terms of what is more appealing to an all-male jury.

Carly Severn: Blanche was seen as an upstanding woman with a respectable profession as a teacher in training. By contrast, servant girl Minnie was a child of divorce with a patchy employment record: a lower-class woman hustling solo in the Bay Area.

Virginia McConnell: She was on her own. She frequently did things that back then would have been looked at askance. She went out on her own. She was frequently out, you know, after dark because she had no one to escort her.

Carly Severn: And it was this necessary self-sufficiency in life that made Minnie ultimately less sympathetic in death — echoing wider male anxieties about the independence that women were increasingly acquiring in the shadow of a new century. But this wasn’t even the only way that the behavior of women was itself tacitly on trial alongside Theo himself. The women who packed out that courtroom became the subject of scathing commentary from the reporters who were there — some of whom, for what it’s worth, were women themselves.

[typing on a typewriter]

Voice reading a newspaper clipping: They were all well dressed, and they all looked like women who had someone who ought to have made them stay home.

Carly Severn: Like several modern serial killers, Theo also attracted admirers – groupies, even, who sent gifts to him in jail. One of these was so infamous she even got her own name in the press: a married Oakland woman dubbed “The Sweet Pea Girl” because of the flowers she lavished upon Theo. But with women of the time shut out from many aspects of public life, it’s not hard to imagine why inserting themselves into momentous events might have held an appeal — even if it’s hard to stomach now.

In the end, it took the jury just 20 minutes to unanimously find Theo Durrant guilty of Blanche’s murder. He was taken to San Quentin State Prison, even as his parents steadfastly campaigned for their son’s release. In January 1898 — almost three years after he killed Blanche Lamont and Minnie Williams — Theo Durrant was executed by hanging age 27. On the scaffold, he gave one last speech, calling himself:

Voice reading Theo Durrant quote: An innocent boy who has not stained his hands with crimes that have been put upon him by the press of San Francisco.

[music starts]

Carly Severn: But after all of the scandal, all of the column inches screaming about gore and sex, it’s the figures of Blanche Lamont and Minnie Williams that should linger with us — not their killer. And it’s hard not to be left with thoughts of Minnie Williams in particular. Unlike Blanche, her death never even warranted a trial.

Virginia McConnell: Minnie was somewhat disposable because she really had nothing going for her. You know, that’s what was in their in their eyes.

Carly Severn: And while Blanche’s body was sent home to Montana for a family burial, Minnie was buried in San Francisco — only to be dug up several decades later when cemeteries started moving south to make way for a growing city. Her body was shipped down to Colma with tens of thousands of others and dumped in a mass, anonymous grave. An “imperfect victim,” discarded just as much in death as she was in life.

[music stops]

Carly Severn: Even though the Emmanuel Baptist Church swiftly resumed services, neighbors clamored for years that the building be demolished and the stain cleaned from Bartlett Street. In 1906, damage from the earthquake forced the issue. Finally, the Church and its infamous belfry were torn down — and every trace of this place was wiped from the face of San Francisco. And in a way, Theo Durrant has been too. Back then, San Francisco thought Theo could be their Jack the Ripper, the ultimate boogeyman stopped in his tracks before he truly could get started. Or, as one newspaper put it:

Voice reading a newspaper clipping: In the criminal history of California, there possibly has never been a fouler double murder committed than that just brought to light in San Francisco.

Carly Severn: Theo was the worst thing the Bay Area could imagine back then. But just think of a few of the infamous serial murder cases that have stalked California and the West Coast since ‘The Demon in the Belfry.’ We’ve had the Zodiac. Ted Bundy. The Manson Family. The Night Stalker. The Golden State Killer.

Virginia McConnell: He’s boring compared to them. So I think that is probably the biggest thing is that it’s no longer a, you know, an anomaly.

Carly Severn: So this may be a slice of Old San Francisco that hasn’t quite kept our attention today. But even as many things have changed beyond recognition when it comes to true crime — and the way it makes us act, makes us feel? Some things never change here.

Olivia Allen-Price: That was reporter Carly Severn. And with that, we blow out the candles on this Boo Curious series. Thank you for listening along. We learned that Sarah Winchester may have just been doing her best when she designed her spooky mansion. We saw how a legend, true or not, can bring a community like Hayward together. Then there was the Church of Satan — more performance art than anything truly sinister. And the Dunsmuir Estate — more of a fixer-upper than a house of horrors. As the saying goes, things are not always what they seem.