Efforts to increase punishments for drug dealers are also escalating locally and nationally. In California, at least two dealers have been convicted of murder charges related to a fentanyl overdose death since last year. Breed’s plan will have San Francisco follow San Diego and Santa Clara counties, which have already moved to charge some dealers with homicide.

“We hope that dealers will decide that San Francisco is not the place for them to be dealing,” Breed said. “People who are dealing these drugs need to be accountable in a way they haven’t been before.”

Nationwide, just 28 people in the country faced drug-induced homicide prosecutions in 2007, but that spiked to nearly 700 people in 2018, based on an analysis of media reports from Northeastern University School of Law.

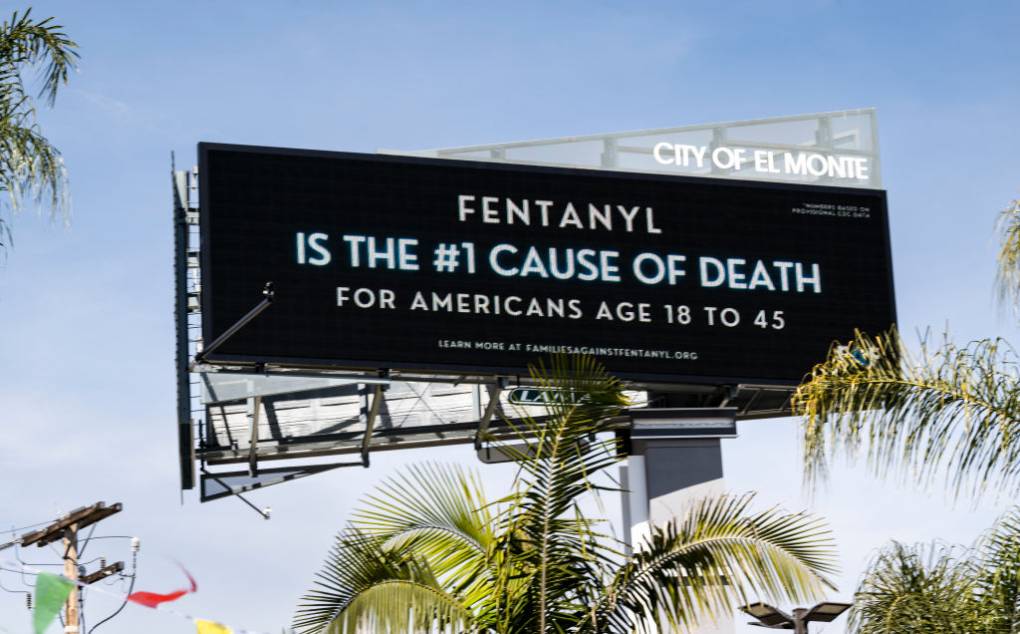

Fatal drug deaths have increased, as well, across the country and the Bay Area in recent years.

San Francisco is currently on track to have its deadliest year on record for overdose deaths. There have been 619 overdose deaths in the city from January to September, according to data from the office of the medical examiner. San Francisco is projected to have 200 more overdose-related fatalities this year than last year.

“Treating opioid deaths similarly to homicides only serves to stigmatize those battling substance use disorders and can discourage individuals from seeking assistance,” said Gary McCoy, vice president of policy and public affairs at HealthRight 360, which provides drug treatment services in San Francisco. “Such an approach also exacerbates cycles of incarceration without achieving the essential objectives of overdose prevention and saving lives in public health.”

The worsening of the city’s overdose crisis that occurred in tandem with those changes has experts, like Chan, deeply concerned about the city’s efforts to move further in that direction.

Public health and harm reduction advocates in San Francisco have for many years been pushing the city to open up more services to address the demand for drugs, like supportive housing, more treatment options and safe consumption sites where people struggling with addiction can use drugs in a medically supervised setting and doctors can reverse an overdose.

“They announce policy after policy that is focused on criminalizing, police-centered approaches, rather than public health approaches,” Chan said. “We urge the mayor, the governor and other city officials, including our DA, to take stock of how much of a failure this approach has been and how harmful it’s been in terms of increasing overdoses.”

KQED senior editor Tyche Hendricks and reporter Oscar Palma contributed to this story.