N

early a decade ago, David Modersbach had what he thought was a straightforward question: How many unhoused people had died that year?

The grants manager and his team at Alameda County Health Care for the Homeless knew people were dying on the streets, but they wanted more than anecdotal evidence; they wanted data that could show them the big picture and help them hone their strategies.

They queried the coroner’s bureau and were stunned by the response: only a single death had been reported.

“We realized there’s a lot of work to do,” Modersbach said.

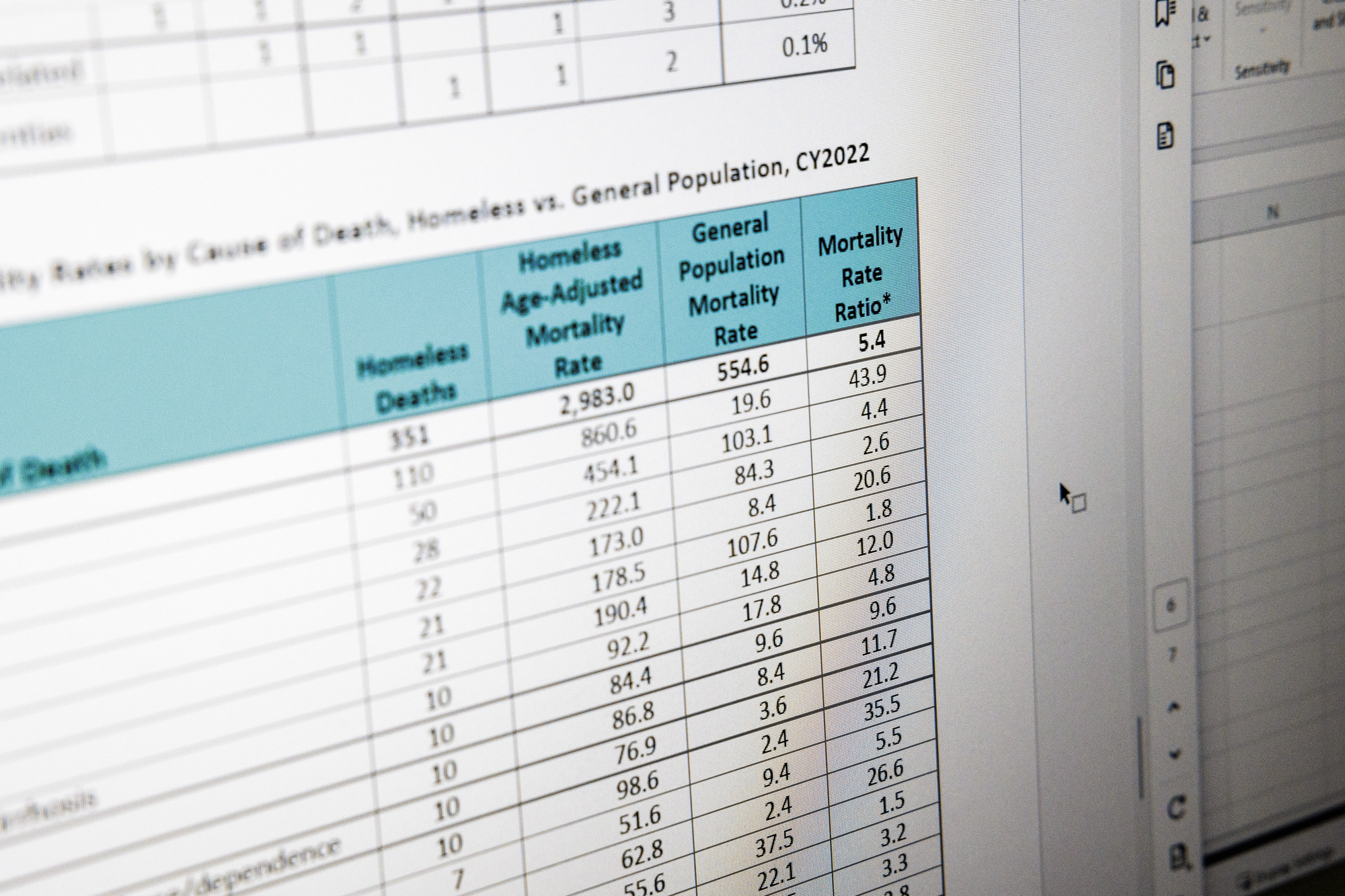

What followed was a bootstrap campaign to fill the data gap. It took years, and the work was sometimes lonely, often tedious and consistently heartbreaking. When the team finally released its first report in 2022, detailing deaths from 2018–20, they counted 195 people in Alameda County who died while homeless in 2018, plus another 189 people with recent histories of homelessness whose housing status couldn’t be verified at their time of death.

As more Californians have fallen into homelessness — a number greater than 181,000 at last count (PDF) — more have died while unhoused, but the state’s ability to track these deaths and assess the scope of the problem hasn’t kept pace.

Spurred in part by Alameda County’s efforts, which are considered a national model for the field, the state recently began taking steps toward collecting this data. In 2022, California added a field to death records for homelessness status, and this year, a law went into effect that empowers counties to set up homeless death review committees to determine the root causes of homeless mortality.

California is among several jurisdictions across the country seeking this data. The pandemic put a spotlight on the health vulnerabilities accompanying homelessness, and that has led to growing national interest in the topic, said Barbara DiPietro, senior director of policy for the National Health Care for the Homeless Council. A recent study from researchers at the University of Pennsylvania and NYU found the death rate of people experiencing homelessness increased 238% between 2011 and 2020.