Episode Transcript

Sounds of BART

Olivia Allen-Price: Johanne Dictor points at the grassy median dividing the six lanes of Martin Luther King Junior Way in North Oakland. An elevated BART track towers overhead.

Johanne Dictor: I guess my grandmother’s house was right here on the, the tracks.

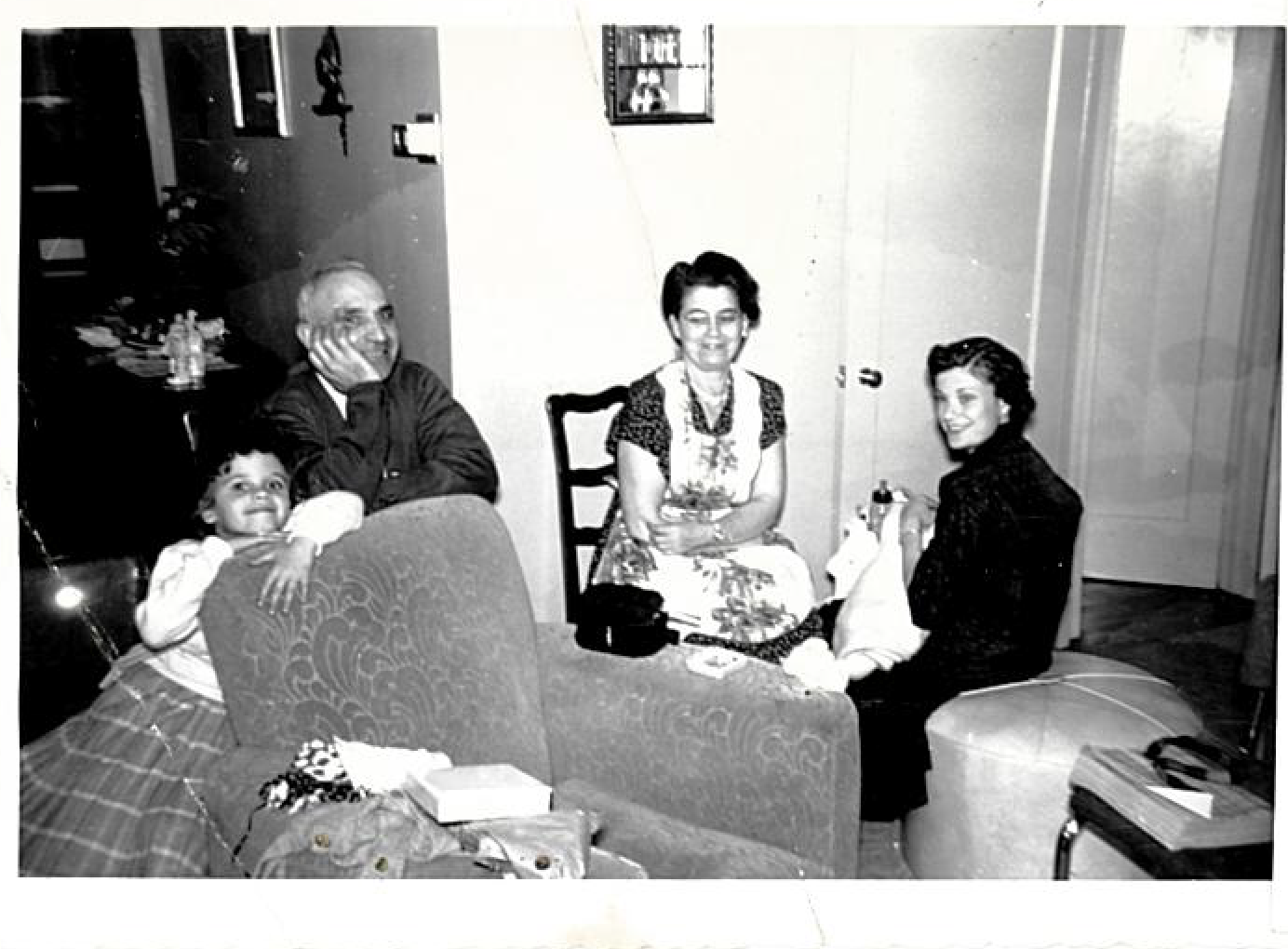

Olivia Allen-Price: Johanne’s grandparents, Vito and Elizabeth Campilongo were immigrants from Italy. They loved their home on what was then 59th and Grove street in Oakland … Grove is Martin Luther King Jr Way these days. They kept the house full of family, friends and, as is the Italian way … good food.

Johanne Dictor: So she, she had this great kitchen downstairs where she made her ravioli. She made her sausages with her women friends. They’d come over, and all day, they’d make sausages down there.

Olivia Allen-Price: And Vito grew food in the backyard.

Janine Dictor: Ah, garden, this master gardener with this beautiful, extensive garden that he used to cook these delicious Italian meals.

Olivia Allen-Price: This was a happy time. But it didn’t last. By the time Johanne was a teenager in the early ’60s, one topic started to dominate their family dinners.

Johanne Dictor: I remember, you know, be sitting at the table and they’d say, you know, they’re, they’re gonna take my house, they say we have to sell it. And we have to leave everything here, and you know, they just were devastated.

Olivia Allen-Price: Ultimately, the Campilongos sold their house to BART and moved to San Leandro. Her grandfather planted a new garden, but it was never as big or as beautiful as the one in Oakland.

Johanne Dictor: He’d sit on the porch like in San Leandro looking so sad, you know, (cries)

Olivia Allen-Price: Johanne’s daughter, Janine, grew up with this family story. But she has always thought it was odd that they didn’t know more about how it all went down.

Janine Dictor: How many properties were acquired? Did anybody challenge, you know, Bart’s ability to acquire their property? What was the outcome of that? Um, yeah, just there seems like there must, there must be a pretty robust story behind all of this. And it’s just odd that we never have known what, quite what it is.

Olivia Allen-Price: I’m Olivia Allen Price, and today on Bay Curious the story of how families like the Campilongos were uprooted to make way for BART. Theirs is a common story — people have been displaced for large infrastructure projects time and time again all across the United States. And it’s still happening today. Stay with us.

Bay Area Rapid Transit…better known as BART…is a fixture of life in the Bay Area today. But many families and businesses were displaced to build it. KQED reporter Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman is going to help us understand how it all went down.

Music starts

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: In the early ’50s, the Bay Area, like much of the country, was in a post-war building boom. New houses were going up all over the region in places like Concord and Fremont. And a big question was how folks would get around.

Sounds of BART promo reel

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: State lawmakers began planning for a regional transportation system to connect the suburbs to the economic hubs of Oakland and San Francisco. There was a lot of excitement … which you can hear in this promotional video for BART.

BART promo reel:…To do this by weaving into the fabric of the Bay Area an entirely new and vastly better way of getting around.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: In 1962, voters in Alameda, Contra Costa, and San Francisco counties approved a nearly 800 million dollar bond to build the new tracks.

BART promo reel:… Locations of lines and stations was the first step in the long planning process.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: But BART needed land, including in residential areas where property was already owned and inhabited by people. The Campilongos neighborhood in North Oakland was one of those areas; another was West Oakland.

Maxine Ussery: When I was a girl, there were… So 7th Street and all of West Oakland was predominantly black, owned by black people. Beautiful old Victorians were there.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: Maxine Ussery was born in Oakland in 1939. Her family, like many Black families at the time, had come from the South in search of work and a better life. Maxine’s mother and father made the journey from Louisiana and settled in West Oakland. They found jobs at the nearby Naval Shipyard.

Maxine Ussery: They had no problems understanding that they had to, in fact, develop their own businesses, their own services, because that’s how they lived in the South.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: She says the West Oakland community had everything they needed…drug stores, groceries, restaurants, churches, doctors and lawyers. But starting in the 1950s, successive government infrastructure projects ripped apart the fabric of this community.

Maxine Ussery: They forced people to move.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: Government agencies demolished homes and businesses for the Nimitz Freeway in the ’50s. Then, in the following decades, they cleared more buildings to make way for Oakland’s Main Post Office and the Acorn housing projects. And then, there was BART. The Oakland Planning Department estimates that upwards of 5,000 units of housing were destroyed in West Oakland in the 1960s alone.

Maxine Ussery: It was like a disbursement of a, of a whole group of a whole community, not just, uh, taking the buildings, it was taking people and who had lived there and who, uh, uh, teachers, um, uh, uh, educate, you know, people who were athletes, all of them were displaced.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: Maxine says the effect on the community was disastrous, especially for the older folks.

Maxine Ussery: They were up in age, and they were moved into areas where they, that where they could afford to go with the money they were given for BART, which was not a lot. It wasn’t enough money for them to live on.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: Many of the infrastructure projects in West Oakland that Maxine talks about were only possible because of a legal tool known as eminent domain.

Radhika Rao: So that’s the part of the Constitution that gives government the power to come along and take people’s private property even if they don’t consent.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: Radhika Rao is a professor of Law at UC San Francisco College of the Law. Eminent domain allows public agencies to buy private property at “fair market value” in order to build infrastructure that is in the public interest. Think hospitals, Public Schools, Highways, Parks, and train tracks. Radhika says without it, infrastructure projects like these might never get built.

Radhika Rao: Because you could have one private property owner who says, my house stands in the way; you can’t build a highway. And then we have no highway. So, our infrastructure depends upon government having this power. It’s, it’s super important.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: But Rhadika says government agencies often target areas with lower property values because they cost less.

Radhika Rao: Of course! That’s, that just makes economic sense, right? Why would government situate your infrastructure in a place where you have to pay more?

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: And the government has a long history of undervaluing properties where people of color and low-income people live and work.

Radhika Rao: And then there are also political reasons, you know, which communities have power, um, and which communities don’t, to organize against this kind of action.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: The 1960 census reveals the parts of West Oakland hit hardest by eminent domain projects were highly segregated … as much as 95% Black … with annual incomes far lower than the city average. The neighborhood in North Oakland that the Campilongos lived in had a higher median income but was also predominantly Black. Rhadika says these communities were vulnerable to eminent domain action and less likely to fight back.

Radhika Rao: Who has the money to hire a lawyer and go to court saying this, the compensation that you’re offering me is not just compensation? It’s not fair market value.

Music starts

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: BART records show that the agency acquired approximately 2,200 properties in order to build its first 75 miles of track. Some people sold their parcels to BART willingly, but others had to be evicted.

Clip of news report: This is Seventh Street on Oakland’s west side.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: In this KPIX news report from 1967, BART staff are evicting an elderly Black woman named Leitha Blick from the thrift store she owns.

News report: An admittedly blighted area, directly in the path of proposed Bay Area Rapid Transit District construction.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: That word — blighted — is important. It’s a term that was used by urban redevelopment agencies throughout the country — including in Oakland — to describe neighborhoods that were seen as deteriorating.

News report: Most of the homes and businesses in this area will have to be destroyed to make room for progress, and the push of progress is not always gentle. Angry and confused, many of the residents say they can’t buy new homes with the market value prices given them for the ones they now live in. Business people face the same dilemma.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: In the news clip, Blick stands by with her arms crossed as workers pack her things into boxes.

News report footage: Miss Blick, had you and the Bay Area Rapid Transit District reached any agreement before this happened?

Blick: No.

News reporter: Why?

Blick: Because, uh, the price wasn’t satisfactory.

News reporter: You didn’t think they were offering you enough money for your merchandise?

Blick: That’s correct. Moving us out, and we had no place to go, and I didn’t think they were offering enough, no way.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: Blick tried to stop BART from taking her property…but ultimately lost. But there are some examples of people successfully altering BART’s plan.

Documentary footage: Berkeley was basically a segregated city. So, the whole of South Berkeley was pretty much a black neighborhood.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: Pam Uzzell’s documentary “Welcome to the Neighborhood” chronicles one effort in Berkeley. It profiles Mable Howard, who argued that BART’s plan to put raised tracks through part of the city would divide it along racial lines.

Documentary footage: A woman who said, I won’t have The city of Berkeley, divided in half, there won’t be any other side of the tracks.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: In 1966, Berkeley voters approved a tax that would pay to put BART completely underground in Berkeley. But BART proposed a design for Ashby station that was slightly above ground. So Mable Howard teamed up with Ron Dellums, then a city council member, to sue the agency. Here’s a lawyer on the case, Matthew Weinberg.

Matthew Weinberg: We won the case. How do we know we won the case? Go to Berkeley. You’ll see the whole thing’s underground.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: BART acknowledges this legacy of displacement and struggle. Here’s Chief Communications Officer Alicia Trost.

Alicia Trost: There was a lot of generational wealth that was deeply impacted, if not destroyed, because of the building of the BART system.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: BART now has an office of civil rights, and other equity initiatives that Trost says are critical to rebuilding trust.

Alicia Trost: And especially when we’re building on our land, uh, we want to make sure there’s a carve-out specifically for affordable housing and that we are in a daily conversation with the community to make sure what we’re building is something that they want.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: As the agency imagines building a possible second transbay tube, Trost says they’re also developing anti-displacement goals.

Alicia Trost: Which, if that’s not lessons learned, you know, I don’t know what is.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: I’ve gone through multiple public records requests and dozens of deeds, right-of-way contracts, and insurance policies for this story. At the end of it all, I paid another visit to Janine, our question-asker, and her mom, Johanne. I had something for them.

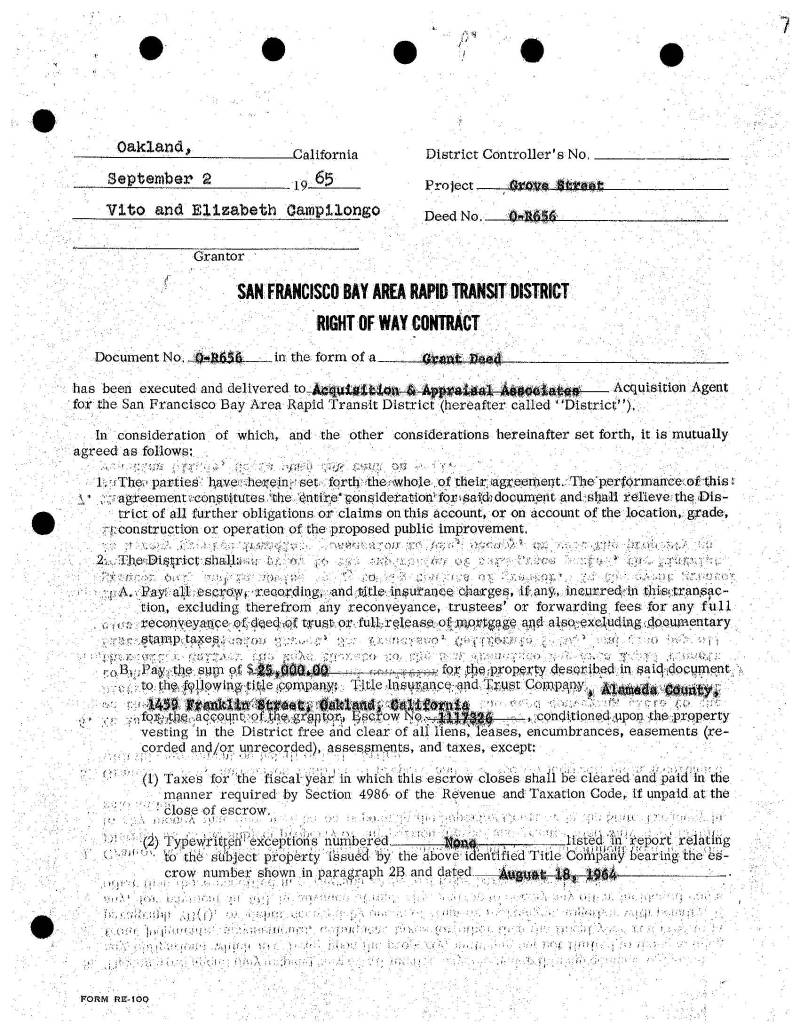

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman, talking to the Dictors: I actually found the contract that your grandparents signed with Bart, so here it is. And so this, you can see, like it says right-of-way contract, and it has your grandparents’ names on it.

Johanne Dictor: Oh, is that all they, so it was just 25,000. Is that right? Oh my God. Oh my gosh.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman talking to the Dictors: We’re looking at the original contract between Vito and Elizabeth Campilongo and the Bay Area Rapid Transportation District, dated Sept. 2, 1965.

Janine Dictor: And it looks like my grandmother’s handwriting, too, actually.

Johanne Dictor: Oh, it does?

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: It shows the Campilongos agreed to sell their property for $25,000. Adjusted for inflation, that’s about 245,000 dollars today. These days, homes go for around a million in that neighborhood.

Janine Dictor: Doesn’t it look like Nana’s?

Johanne Dictor: Not really.

Janine Dictor: That floral?

Johanne Dictor: Yeah, a little bit, but hers was, yeah, she had a good penmanship, Nana. Yeah,

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: Janine and Johanne are excited to see the physical evidence of their family history. But after the initial excitement, the mood is somber.

Janine Dictor: Going through this process, it’s like you realize it’s like about a lot more than what they were compensated, right? It’s about the fact that they were forced into this, that they lost a lifestyle, that they lost a community, you know. So, even if they got a good price, it’s kind of like, there’s still something to mourn there right about their experience.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: The word progress comes up a lot when talking about these kinds of projects. The idea is that progress, the greater good, justifies the sacrifice some families have to make. But for families like the Dictors, progress could feel like a step in the wrong direction. Here’s Johanne.

Johanne Dictor: After we lost that house, we lost the sense of our family in a way, it seemed like. It was kind of driven apart. Because that house really brought us together. More than the house in San Leandro, you know.

Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman: Public infrastructure is often seen as a kind of equalizer … it’s something we all pay for and that anyone can use. But the fact is … some people had to pay more than others.

Olivia Allen-Price: That was KQED reporter Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman.The use of eminent domain led to the displacement in some of the stories we explored today. It was often used to displace communities of color to make way for various infrastructure projects around the state. As part of its reparations efforts, California is now considering a bill that would compensate people if they can prove racism or discrimination prevented them from getting just compensation. To learn more about California’s reparations efforts, check out KQED’s coverage at KQED dot org slash reparations.

Special Thanks to Pam Uzzell for allowing us to use clips from her documentary “Welcome to the Neighborhood” in this story.

Katrina Schwartz: This episode was edited by Katrina Schwartz.

Olivia Allen-Price: Produced by Olivia Allen-Price.

Tamuna Chkareuli: Tamuna Chkareuli

Pauline Bartolone: Pauline Bartolone

Christopher Beale: And Christopher Beale.

Olivia Allen-Price: We get additional support from:

Jen Chien: Jen Chien

Katie Sprenger: Katie Sprenger

Cesar Saldaña: Cesar Saldaña

Maha Sanad: Maha Sanad

Xorje Olivares: Xorje Olivares:

Olivia Allen-Price: And the whole KQED family. Have a great week, everyone.