So, at the beginning of the 2022–23 school year, the district hired an outside firm called SchoolStatus to track attendance data and communicate with parents via texts, emails and postcards in multiple languages. Fish said it has freed up his staff to make phone calls or home visits to better understand the reasons behind the absences and offer help such as counseling or connecting families to social services.

“Rather than say ‘what’s going on? You’re going to get a citation,’ why not call and say ‘hey, we miss having [your child] in school. How can we get him here? What can we do to support him?’ I think that’s why we’ve seen some progress over the last two years in terms of our attendance,” Fish said, adding that the district’s chronic absenteeism rate improved by 10 percentage points.

School districts across California are investing hundreds of thousands of dollars in efforts to detect chronically absent students, or to hire firms to do that work for them, because the amount of state funding they receive depends on enrollment and attendance.

Alvord Unified pays School Status $240,0000 annually for its service, using state funding for post-pandemic learning recovery. The company said in a report released Tuesday that school districts that use its attendance management strategies saw a 22% reduction in chronic absenteeism between the 2021–22 to 2022–23 school years.

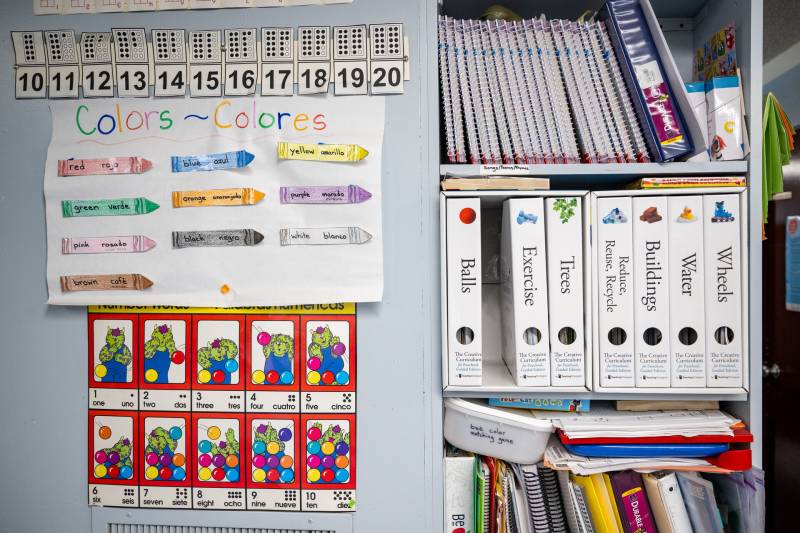

“We like to say we’re creating a culture of achievement, starting with creating a culture of showing up,” said Grace Spencer, an attendance expert at SchoolStatus. “It starts with notifying parents in a timely, consistent manner, with positive messaging in their family’s home language.”

The messages may start with a notification about how many days their child missed school, how much learning time they missed compared to their classmates, and how students who are chronically absent are likely to struggle academically.

If the absences continue, the system will step up its warnings but it tries to focus on encouraging and celebrating attendance, she said.

“Postcards that say ‘we love it when you’re in school. We miss you when you’re not here.’ It’s that personal touch [saying] we want you in school, and school is important,” she said.

Sending text messages and postcards with language that “stresses common purpose and is more warm than judgmental” might be an effective, low-cost solution to chronic absenteeism, said Stanford University education professor Thomas Dee.