Episode Transcript

This is a computer-generated transcript. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Olivia Allen-Price: When Naomi Barrios and her sister Rosie were teenagers in the 1980s, they would look forward to cruising around Salinas every Friday and Saturday night. They’d roll low and slow, down Alisal Street.

(music begins)

Naomi Barrios: That was the best. Meeting people, seeing cars, having fun, enjoying the music, flirting with guys. It was fun!

Olivia Allen-Price: Naomi and Ros would cruise in a burgundy Pontiac Firebird … sporty looking car … with a regal yellow firebird painted on the hood.

Naomi Barrios: After we would cruise a little bit, a couple times, you know, three times. Then we would park, at a Winchell’s Donut place. That was our spot.

Olivia Allen-Price: In the parking lot people, mostly from Salina’s Chicano community, would line up their immaculate cars and show off their newest modifications. I’m talking leather seats, shiny rims and precise paint jobs. These cars weren’t simply modes of transportation. They were creative vessels, canvases for artistic expression, one’s pride and joy.

Naomi Barrios: It was a big crowd hanging out there outside. Inside everybody ordering, chatting. Everybody had their music on. Again, just looking at their cars, meeting new people, making new friends.

Olivia Allen-Price: The whole thing … it was a scene. One that was popping up in communities all across California. That’s because California is the birthplace of lowriding culture … but where exactly that birthplace is has been a point of contention. Some folks say Lowriding started down in L.A., others say things got going in San José.

Olivia Allen-Price: A Bay Curious listener asked us to unpack the dispute. You selected the question in a public voting round. So, today on the show, we’ll explore the lowriding origin story … or stories. Then, we’ll learn how lowriding became criminalized, and catch up on where things are at today. I’m Olivia Allen-Price. We roll … right after this.

Sponsor Message

Olivia Allen-Price: So, did lowriding start in San José or L.A.? Or somewhere else all together? To start today’s episode, Bay Curious intern, Ana De Almeida Amaral, headed out to a car show to get the lay of the land.

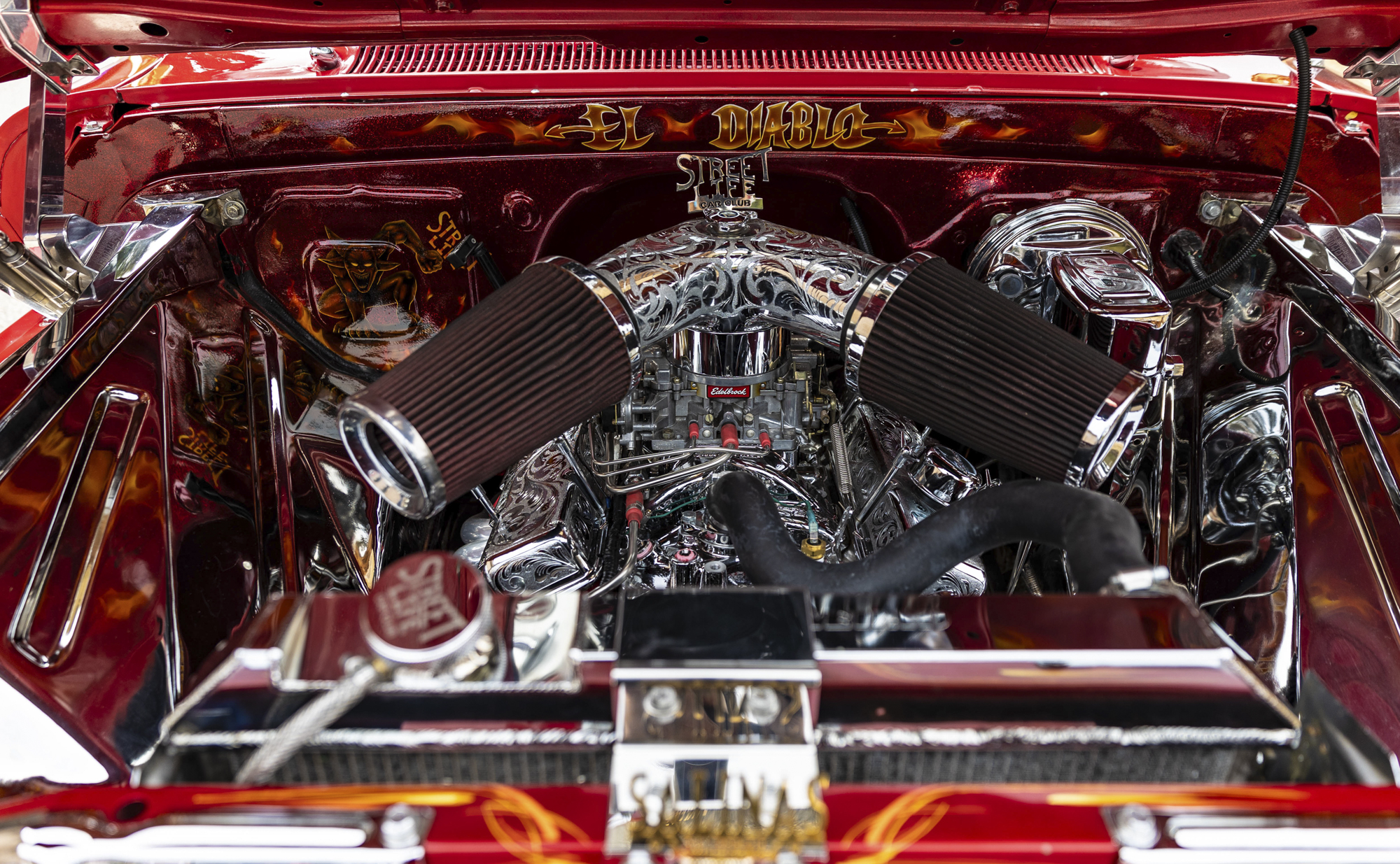

Ana De Almeida Amaral (in tape): So I’m in a parking lot and there are dozens of cars just parked along both sides, and they’re painted all sorts of beautiful colors.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: Right behind the palace of fine arts in San Francisco, over a hundred people are gathered for the King of the Streets car show. In the middle of the parking lot, a sparkly, lime green Chevy is parked — with the hood popped revealing a shiny chrome engine. Nearby is a light blue two-seater, with a painting of a nude woman on the hood. The car is balanced on three wheels — one wheel 3 feet in the air — showing off its hydraulic suspension.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: People stand around cars that look like art pieces, drinking, eating, and talking all about the features. A car owner named Carlos brags about his ride.

Carlos: That’s my car right there, El Mas Gangster de Todos. It’s a 1948 Buick Super 50. It’s all original … original chromes, original paint.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: As I walked down rows and rows of lifted, candy painted, and tricked out cars, I bumped into Anthony, who was wiping his white car’s exterior with a towel even though, to me, it already looked pristine.

Anthony: This is a 1969 Chevy Caprice, it has a 350 small block, uh brand new block. It has hydraulics, it’s lifted front and back — were from the BLVD Kings Car Club.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: And how long have you been working on cars?

Anthony: Oof, since I was a kid.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: He points to an older man working on the car with him.

Anthony: He basically taught me everything I know, the first car I remember him having was a ’72 Impala, so that basically got me into it. And then I remember growing up in the mission, seeing all the mini-trucks going up and down the mission. So, it’s been all my life.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: Other people I spoke to shared the same passion for this art form and a deep pride in the lowriding culture. But when I asked about the origins of lowriding, I got a lot of answers …

Ana De Almeida Amaral (in tape): Where do you think that it got started?

Anthony: Oh, L.A. all day. Everybody knows, lowriding got started in L.A.

Man 1 at the car show: In my hometown, Turlock, California. Cause I was a kid from there! [laughs]

Man 2 at the car show: Hmmm, it’s been said San José.

Man 3 at the car show: From what I understand, it started somewhere in Baja California.

Robert: I think it started with every little kid who had a Hot Wheels and stole their mom’s nail polish and started candy painting their hot wheels.

Olivia Allen-Price: Out on the streets, Ana didn’t find a straight answer, so we passed it off to reporter Sebastian Miño-Bucheli to dive deeper into the world of lowriding.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: It’s clear that within the lowriding community, this matter isn’t settled. So I talked to someone who has been studying lowriding for a long time … Professor John Ulloa.

John Ulloa: It’s debatable. I mean, it’s hotly debated. Hotly debated. Everybody wants to claim ground zero for low riding.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: Ulloa is the dean of arts and social science at West Valley College. He says one tough thing about this question is that lowriding has evolved a lot over time …

John Ulloa: A lot of people say, well, it’s a it’s a car with hydraulics on it. But if you’re looking at culture and you’re looking at stance of car, you’re looking at attitude, you’re looking at aesthetics. Um, you know, the clothing and in tandem with the cars and, you know. Just the presence of, you know, how one presents themselves culturally… I think that we really have to be looking at the pachucos of the 1940s.

(Jazzy mellow music from the 1940s era)

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: Here comes the argument for Los Angeles being the birthplace of lowriding …

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: The pachucos were a subculture of predominantly Mexican American young people that thrived in East Los Angeles around World War II. Pachuco means “Punk” in Spanish

They were kids during the Great Depression, and had seen their friends and family members of Mexican descent deported en masse, even those who were American citizens. It was part of the U.S. government’s “repatriation” program … which ultimately saw the mass deportation of about a million people.

John Ulloa: These kids, by a white dominant paradigm, were othered and seen as foreign.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: The U.S., and white society had not treated their families well, so the pachucos were all about resisting assimilation, and instead creating something of their own.

John Ulloa: Pachuco culture is provocative in nature.

(music ends)

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: During World War II, many Americans were showing their patriotism by rationing … using less gas, eating less food, not buying new clothes. The idea was to save resources for the war effort. But the pachucos … they were rocking the Zoot suit.

John Ulloa: You have an exaggerated aesthetic with ballooned out pants, exaggerated shoulders in the coats. Um, you know, topped off with a nice hat with a big single feather.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: This clothing style came from jazz culture and it was popular amongst Black, Latino and Filipino youth.

John Ulloa: So the whole presentation was really flamboyant and seen as not only criminalized but completely un-American.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: Around this time, in the ’40s, White Americans were hacking their hotrod cars to go fast. So pachucos did the exact opposite. They went low and slow … sending a clear message about their nonconformity.

John Ulloa: Necessity is the mother of all invention, right so. It was cheap to get a ’30s car and work on it, you know make it your own. You lower it in the back or you lower it all the way around.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: And this was decades before hydraulics came on the scene, so getting low meant filling the trunk.

John Ulloa: You slam it quote unquote as we say. Literally. With sandbags, with rocks, with cinder blocks, with bricks, whatever you could find that was heavy to put in the trunk. What that would do is that would take the car from sitting level, to being lowered in the back.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: The pachucos also pushed against the grain with candy-colored paint jobs and Chicano art. These cars were a loud and proud statement about their culture.

John Ulloa: Low and slow was the antithesis of hot rod fast.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: So if we’re looking at who are the OG lowriders, the first to start driving low and slow, Los Angeles and the pachucos have a compelling argument. But then where does this San Jose argument come from? What stake does that city have in lowriding culture?

John Ulloa: The San José argument largely has to do with it’s the birthplace of Lowrider magazine.

(Mellow 1970s era music)

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: In 1977, a guy named Sonny Madrid was a student at San Jose State. With a few friends, he launched Lowrider magazine, a monthly that celebrated Chicano culture.

John Ulloa: It was a lifestyle magazine. It wasn’t just cars and vehicles. It was people. Right …

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: The magazine had articles about fashion, music, politics. And it was hitting newsstands at just the right time.

John Ulloa: The Golden Era, as I’ve timestamped it, was from 1977 to 1982 and those were the first five years of Lowrider magazine. People were already lowriding prior to Lowrider magazine, but now what Lowrider magazine did is it was able to give everyone access to see what people were doing all over the Southwest, right?

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: It helped solidify lowriding as a culture. And then it exported that culture making it into a global phenomenon. The Letters to the Editor section of the magazine put that on full display.

John Ulloa: There were letters in there from Great Britain, Scandinavia, France, Germany, all over the world. People are saying, “Hey, I just got your magazine in my hand, and this is so cool. We don’t have this here, but as soon as we can, we will.”

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: And when there’s a global phenomenon going around, there’s always a local take on the phenomenon. Each city adds their own flare to lowriding. People in the know can often spot a Bay Area lowrider versus one from L.A. or one from San Antonio, or Japan. Maybe it’s a custom paint job. Or a tire size popular in a certain area. Everywhere lowriding goes, the community leaves a mark.

(Blues begins)

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: At the end of the day, Ulloa won’t settle the debate about if lowriding started in Los Angeles … or if what came out of San José and Lowrider magazine was so unique it was something new altogether …

John Ulloa: Safely we can say that lowriding originates in the Mexican American experience in the southwestern part of the United States.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: To Ulloa, where lowriding started doesn’t matter. But why people care does.

John Ulloa: The real question is why are people planting that flag? That’s the deeper question and everybody wants to own history. Especially communities that have historically had their histories systematically erased, swept under the rug, ignored, altered, unheard.

(Music in the clear for a few seconds and then fades)

Olivia Allen-Price: Sebastian, Lowriding has such a fascinating history in this state. And while we can celebrate that it was born here, it hasn’t always been accepted here. Can you explain how lowriding first became criminalized?

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: If we go back to the pachucos in the 1940s, they were surrounded by military personnel in Los Angeles waiting to leave to fight in World War II. And the presence of pachucos did not sit well with them. They thought zoot suits were unpatriotic … a sign of gang affiliation. And that’s a narrative that the local press really fed into.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: There were a series of violent clashes where off-duty servicemen, police and white civilians attacked the pachucos, known as the Zoot Suit Riots. Anyone caught by the mob were stripped of their zoot suits and beaten. That’s where we start to see pachuco culture become targeted by police. Racial profiling is happening. And it extends to people driving lowriders. This criminalization of lowriding would play out for decades to come.

Olivia Allen-Price: In 1982, the state of California passed a law that allowed cities to implement cruising bans … over concerns about traffic, noise and crime. It also set limits on how much a car could be lowered. And then Soon after that cities like Sacramento, Fresno, L.A. and San José all had cruising bans on the books. What happened to the community in those places?

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: The culture didn’t go anywhere, but people did get creative. People kept lowriding, eventually car shows started happening. These were sanctioned events where the lowriding community could still gather. But ultimately, activists started working to change things. And it worked! Just last year, California passed AB 436, a law that overturns the cruising bans, and lifts that prohibition on how low cars can go.

We’re still seeing how it all plays out on the local level, but this last May, East San José had their first lowrider event since the ban was lifted for Cinco de Mayo. And people I spoke with there were optimistic about the future. And they were really happy to be there that day to share in the community and culture. They said finally we’re able to do this again!

Olivia Allen-Price: Sebastian Miño-Bucheli. Thanks for your reporting on this one.

Sebastian Miño-Bucheli: You’re welcome.

(Music with trumpets begins)

Olivia Allen-Price: KQED’s podcast The Bay has an excellent episode from when the cruising ban was lifted last year, that gets a lot more into how it was criminalized. It’s called “California Lifts Decades-Old Ban on Lowrider Cruising.” We’ll link to it in our show notes.

Olivia Allen-Price: Also in our show notes is a link to the web story for this Bay Curious podcast episode — check it out for some awesome photos of that lowrider car show our intern Ana went to, along with several videos KQED has produced about lowriders over the years.

Olivia Allen-Price: Bay Curious is made in San Francisco at member-supported KQED. If you like what we’re doing here at Bay Curious, please consider becoming a KQED member today. Learn more at KQED.org/donate.

Olivia Allen-Price: This episode was produced by Ana De Almeida Amaral, Amanda Font, Christopher Beale, and me Olivia Allen-Price. Special thanks to Katrina Schwartz, Katie Sprenger, Jen Chien, Maha Sanad, Holly Kernan and the whole KQED Family.

Olivia Allen-Price: I’m Olivia Allen-Price … hoping you have a wonderful week. Bye!