T

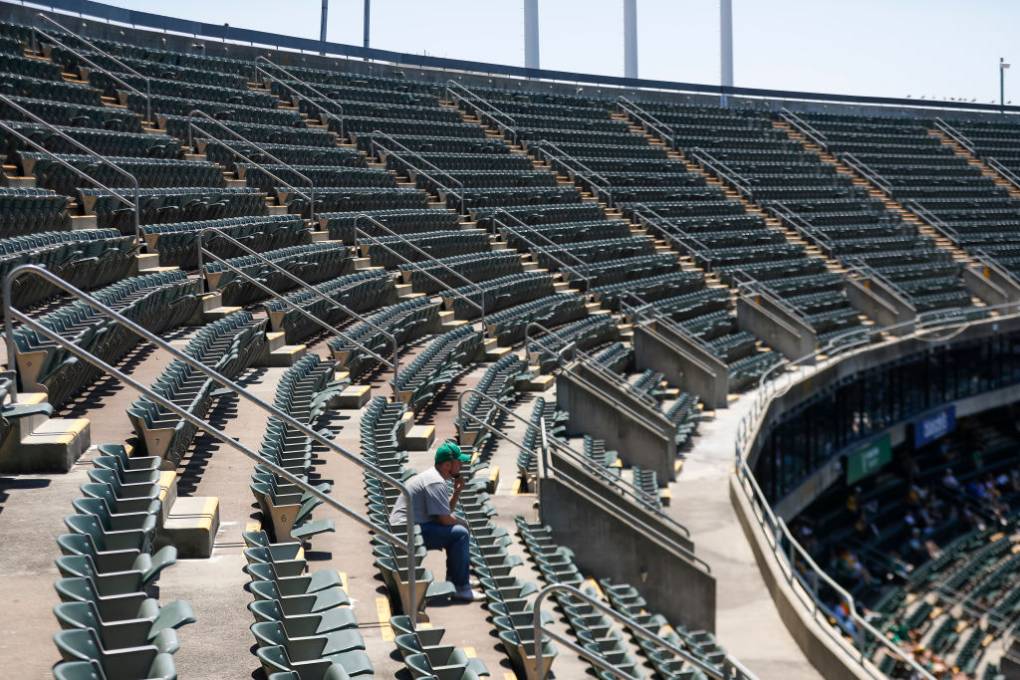

he Oakland A’s will play their final home game this week — a long-anticipated, sold-out event that will be an adventure in mass catharsis: surges of grief and anger and loss mixed with waves of gratitude from the team’s tight-knit community of fans for everything A’s players and Coliseum workers have given them over the past 57 seasons.

It couldn’t be more different from the A’s departure from Philadelphia, their original hometown: Hardly anyone came to say goodbye.

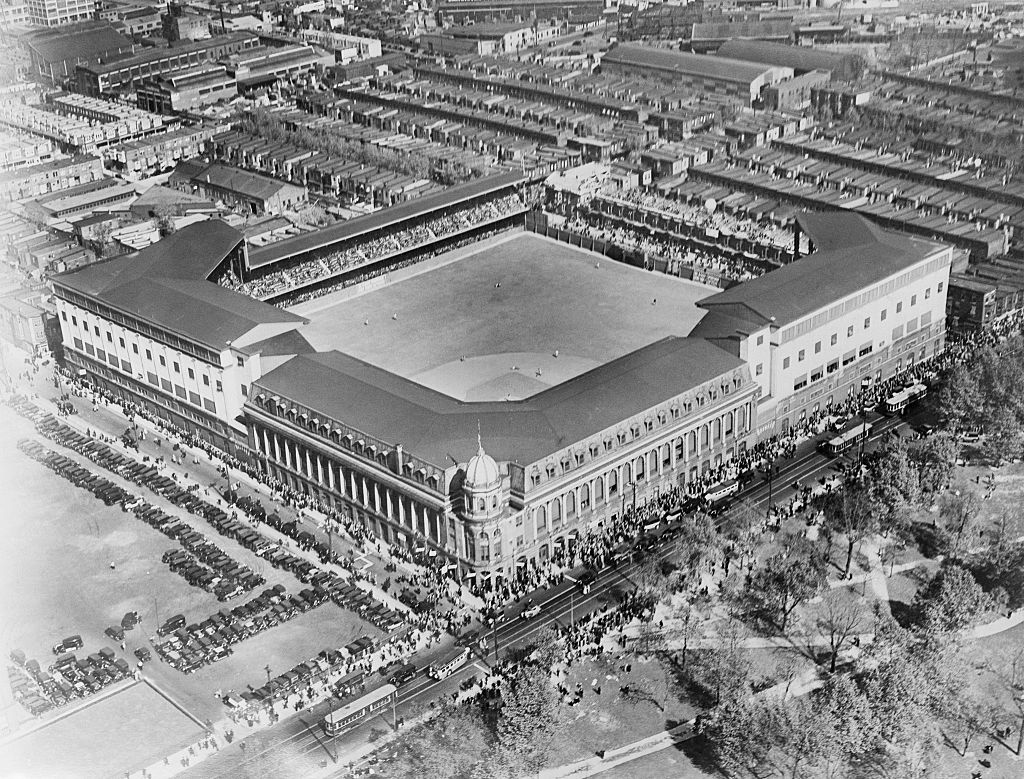

On a gloomy September Sunday 70 years ago, near the end of a season The Philadelphia Inquirer summed up with one word — “dismal” — the Athletics lost to the Yankees in a virtually empty ballpark. On the team’s next opening day, they were playing halfway across the continent.

Why wasn’t the scene at Philadelphia’s Connie Mack Stadium even a little dramatic as the Athletics’ time in the city ended?

Long before the end of the 1954 season, Philadelphians knew the A’s were in trouble.

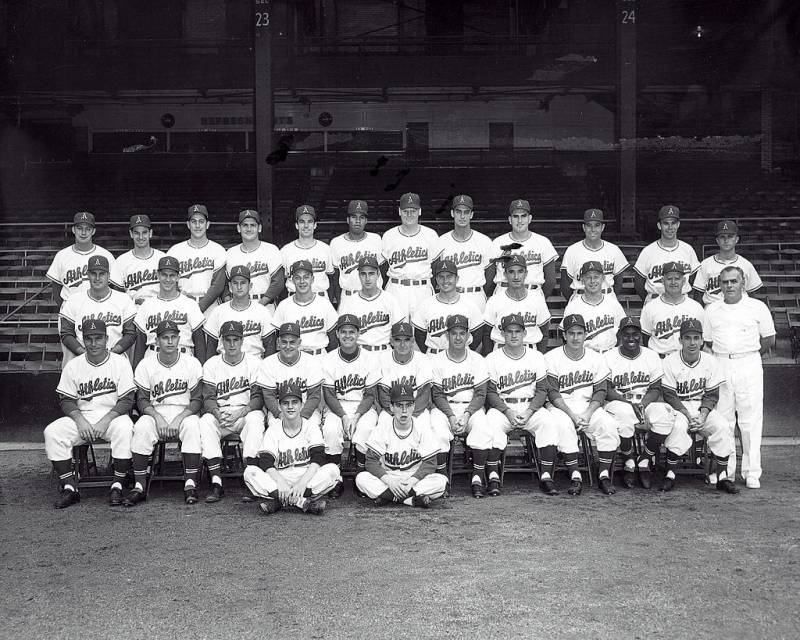

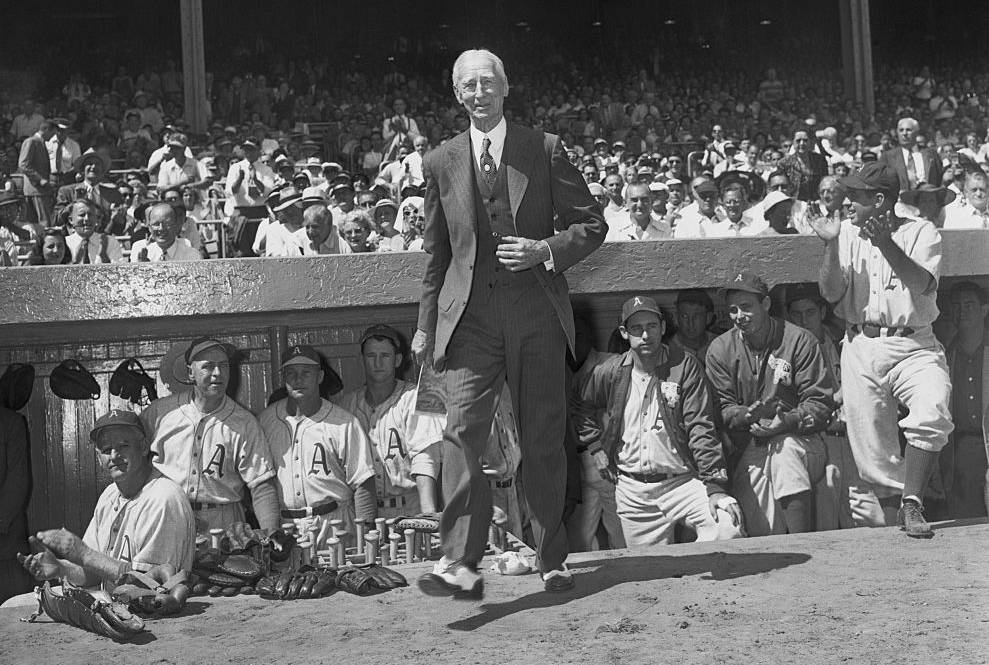

The team, owned by legendary manager Connie Mack and two of his sons, Roy and Earle, was broke. City officials and community leaders joined in a “Save the A’s” campaign to stoke enthusiasm for a team with a storied past: nine American League pennants, five World Series championships.

The A’s let it be known in mid-season that if they could draw 550,000 paying customers, they’d have a shot at avoiding bankruptcy and a sale that could well result in the team moving.

But the A’s were a very bad team that had been, with few exceptions, very bad for a very long time. In the previous 20 seasons, the team had won more games than it lost only four times and never finished better than fourth in the eight-team league. The team’s customary finish was last place, and in 1954, it was headed there again.

“The A’s kept announcing, ‘We need so many people per game to come so we can reach our 550,000 fans,’ and the fans just kept ignoring it,” says Bob Warrington, a Philadelphia baseball historian who’s written about the A’s departure.

“I think what the A’s failed to realize, certainly Roy and Earle, was that baseball fans are not customers,” Warrington says. “They’re fans, they’re supporters. And you can’t threaten them into coming to the ballpark by saying, ‘If you don’t come, you know, we may not be here next year.’ You’ve got to encourage them to come.”

So the “Save the A’s” campaign fizzled, even as an out-of-town bidder made a highly publicized offer to buy the team and relocate to Kansas City. As autumn neared and the New York Yankees arrived for the season’s last home series, attendance stood at just under 300,000 — a little more than half what the A’s say they’d need to avoid financial disaster.

The Yankees won the first two games in front of tiny crowds on Friday and Saturday. The attendance on Sunday, Sept. 19 was even lower — just 1,715 fans pushed through the turnstiles — as the Yankees swept the series. It was just another loss in a season that everyone wanted to forget.

Within days, the American League would open talks on the future of the franchise. In early November, Connie Mack and his sons sold the team to — and the league approved the franchise’s transfer to — Kansas City.

Why did it come to this? Did the A’s have to leave? Here are some of the major factors: