That whole decade was a period of social and cultural change. There was the civil rights movement.

Martin Luther King, Jr. (clip): We will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood…

Olivia Allen-Price: Women’s liberation…

May Craig question to John F. Kennedy (clip): …for equal rights for women, including equal pay…

Olivia Allen-Price: It was a time when the very fabric of society was being questioned, and people were having big ideas about how people think and how people are taught.

It was against this backdrop that the Black power movement was getting traction

Malcolm X (clip): We are oppressed. We are exploited. We are downtrodden. We are denied not only civil rights but even human rights.

Olivia Allen-Price: The Black Panther Party for self defense was founded in Oakland in 1966, as a strategy for organizing against rampant police violence. They believed in Black nationalism, socialism, and armed self-defense against police brutality.

Ericka Huggins: The first thing that drew me to the Black Panther Party that I always remember about it… it said the Black Panther Party for Self-defense and Self-defense, people get their hackles up about that.

Olivia Allen-Price: This is Ericka Huggins. She joined the Black Panther Party in 1968.

Ericka Huggins: People think that self-defense is physical. It can be and needs to be when necessary. However, this was about supporting people who live poor and or oppressed.

We said you cannot continue to kill us. You can’t break down our doors to our homes and shoot at us. You cannot arrest us, wrongly incarcerate us and beat and murder us while we are incarcerated. You cannot deprive us of food, housing, clothing and peace. J. Edgar Hoover said that the Black Panther Party is the greatest threat to the internal security of the United States.

Olivia Allen-Price: While the Black Panthers had a reputation as a militant group, they did way more than challenge the police and protest against racist policies.

The panthers created a long list of community service programs that they called “survival programs”. They provided things like Free Health Clinics, Consumer Education Classes, and an Employment Referral Service.

I’m Olivia Allen-Price and this is Bay Curious. Today, we’re playing an excerpt from KQED’s MindShift podcast … about one of the “Black Panther Party’s longest-running programs – an elementary school run mostly by women. It was a small school, but made a big impact, and its legacy lives on today. We’ll get into all that right after this….

SPONSOR MESSAGE

Olivia Allen-Price: Here to walk us through the history of the Black Panther’s foray into education is Nimah Gobir, host of KQED’s MindShift podcast.

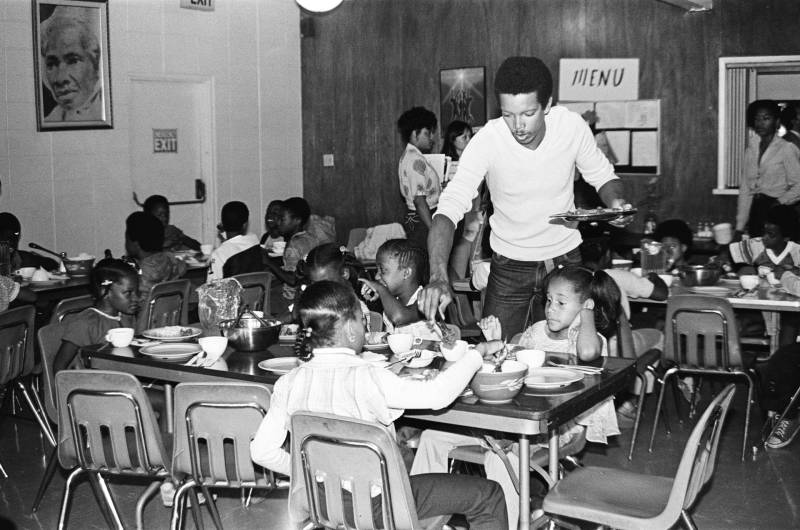

Nimah Gobir: If you look up pictures of the Panthers– yes you’ll see guns and berets, but there are other images too. And the one that sticks with me is this photo of a Black Panther Party member putting down plates of food in front of young children. It’s a photo of their free breakfast program

Ericka Huggins: Children were expected to go to school and learn without any food. We knew because we were those children.

Nimah Gobir: They had a founding charter which included a 10 point platform. I won’t go into all of the points but it basically said that our people – Black people– need to be able to eat, find work and feel safe. This episode we’ll talk about point 5, a focus on a fulfilling and effective education system

Bobby Seale Speech at Oakland Auditorium (clip): We want decent education for our Black people in our community that teaches us the true nature of this decadent racist society and to teach Black people and our young Black brothers and sisters their place in this society because if they don’t know their place in society and in the world, they can’t relate to anything else.

Angela LeBlanc-Ernest: Education was always important in the party.

Nimah Gobir: Angela LeBlanc-Ernest is a documentarian and community archivist from Texas. She has studied and written books about the Panthers pursuit of education.

Angela LeBlanc-Ernest: Whether it be the study sessions they had reading the different books by revolutionaries – political education classes is what they would call them – that were required, or whether it was party members tutoring kids in the local community.

Nimah Gobir: She told me the idea to create a school came about when party members saw how their own kids were mistreated in mainstream schools

Angela LeBlanc-Ernest: You had to start envisioning what society needed to look like for your child if they survived. Right? There is a sense so many of them didn’t think they would survive

Nimah Gobir: Party members started to conceive of a community-based alternative to the poor educational experiences they had as children. They were often disciplined harder and discouraged from asking questions. Their schools lacked supplies and books, and the curriculum rarely included stories of people who looked like them.

Nimah Gobir: So in response to this they opened the Intercommunal Youth Institute in east Oakland in 1971

Angela LeBlanc-Ernest: It was an old church that they converted into a school and so it was a small space. They decided that they wanted to start with the number they had, which was 50 students.

Nimah Gobir: Gradually, other people noticed that the students and families were being treated well at this scrappy little home school where they used mindfulness practices and restorative justice. Students were engaged, respected, and learning in an environment that valued their heritage and experiences.

Angela LeBlanc-Ernest: When the community approached the Black Panther Party, when it was just the insular home school to say, “Hey, can you make this available to the community, to children in the community?” That was a prompt for them to think more broadly.

Nimah Gobir: As new people joined from outside of the party, they began outgrowing the space and so they had to look for something more permanent. They changed the name to Oakland Community School and Black Panther Party member Ericka Huggins became the director.

Ericka Huggins: We opened the Oakland Community School in the school year of 1973-74.

Nimah Gobir: Students were ages 5 -12, so it was basically an elementary school, but there were no grades. They were grouped according to their academic abilities. They also had childcare for kids who were younger than five.

Nimah Gobir: Many of the students came from the Oakland area but some were coming from the greater bay area too.

Ericka Huggins: We had more than party members on staff. Not only did the people take their children out of public school, the public school teachers left, too, to work at… as it used to be, nicknamed the Panther School.

Nimah Gobir: This school is special for a lot of reasons, but one of the big reasons is that it was one of the earliest versions of community schools in the country.

Ericka Huggins: The school was community based, child centered, tuition free, parent friendly and we paid special attention to children whose families had trouble with clothing and food.

Nimah Gobir: Nowadays when we talk about community schools, we’re talking about schools like this one, that provide for the whole child beyond academics. Often these schools have the things that families need located at or provided by the school. Oakland Community School provided groceries to families in the community and food throughout the school day.

Ericka Huggins: Three meals a day and I said it was tuition free. The meals were also for the students and staff of the school.

Nimah Gobir: If parents couldn’t afford the city bus. A bus from Oakland Community School would come pick their kids up. They used curriculum that actually reflected the students that were going to the school

Ericka Huggins: Our motto was “the world is a child’s classroom.” Which is a little different than the United States is the center of the universe.

Ericka Huggins: We talked about the enslavement of Africans. We talked about the indigenous people. We talked about the resilience and brightness of our ancestors and our generations up to them and how beautiful and bright they are. We always affirmed the children. We wanted them to know about history. We wanted them to know about themselves as people coming from great ancestry no matter their race or ethnicity. We didn’t ever turn away a student because they were not Black.

Nimah Gobir: Students at the so-called Panther school were Black –but they were also Latino they were white students they were Asian students and biracial students

Ericka Huggins: When people see this, they’re shocked, like, oh, why are you shocked? We were the Black Panther Party and they have to think about what they’ve been told.