View the full episode transcript.

Every October, navy planes rip through San Francisco skies, giant warships barrel through the Bay, and hundreds of uniformed officers fill Marina Green. Then, a week later, they’re all gone. It’s all part of Fleet Week, a 40-year-old military tradition in San Francisco.

These days, Fleet Week is likely the only time Bay Area residents see armed forces in uniform. Although the military’s presence in the Bay Area was once huge, the Department of Defense began a national effort to downsize in the late 1980s, leaving many former military sites vacant and in need of cleanup.

Bay Curious listener Cameron Tobey wondered about this history while exploring the former Mare Island Naval Shipyard in Vallejo.

“It seems at one point that every branch of the military had a base here, and now they’re all sitting empty,” Tobey said. “So what happened to them, and what’s the future plans for these bases?”

The Bay Area was once a military powerhouse

Dating back all the way to Spanish colonizers who built the Presidio, San Francisco was a strategic place for military defense. When the United States took over, it grew into one of the biggest military centers in the world.

“San Francisco was the overwhelming center of U.S. settlement, economy and power in the western U.S. in the 19th century,” said Dick Walker, professor emeritus in geography at UC Berkeley and author of several books on California history.

By the end of World War II, the U.S. military had established dozens of sites, everything from shipyards and air stations to barracks and weapons stations.

Many former military sites have become iconic Bay Area landmarks. Alcatraz was once a military prison; Treasure Island housed Navy bunkers and San Francisco’s Fort Mason was a launching point for over a million soldiers heading to the Pacific.

But the military presence reaches far beyond these well-known places. During World War II, the Hunters Point Naval Shipyard repaired warships. In the Marin headlands, soldiers lived at Fort Baker and Fort Cronkhite, and the Nike Missile Site was ready to strike down Russian H-bombs during the Cold War.

In the East Bay, Oakland’s Army Base sent soldiers and supplies overseas. And Camp Parks in Dublin was a home base for the Seabees, the navy’s construction crew. At the Concord Naval Weapons Station crews loaded and shipped massive quantities of explosives. And Alameda’s Naval Air Station was called the Navy’s “aviation gateway to the Pacific.”

In the South Bay, the Naval Air Station at Moffett Field specialized in anti-submarine warfare. And in addition to all the military personnel stationed at these sites, far more Bay Area residents were involved with producing the materials and supplies they needed.

World War II transformed the Bay Area

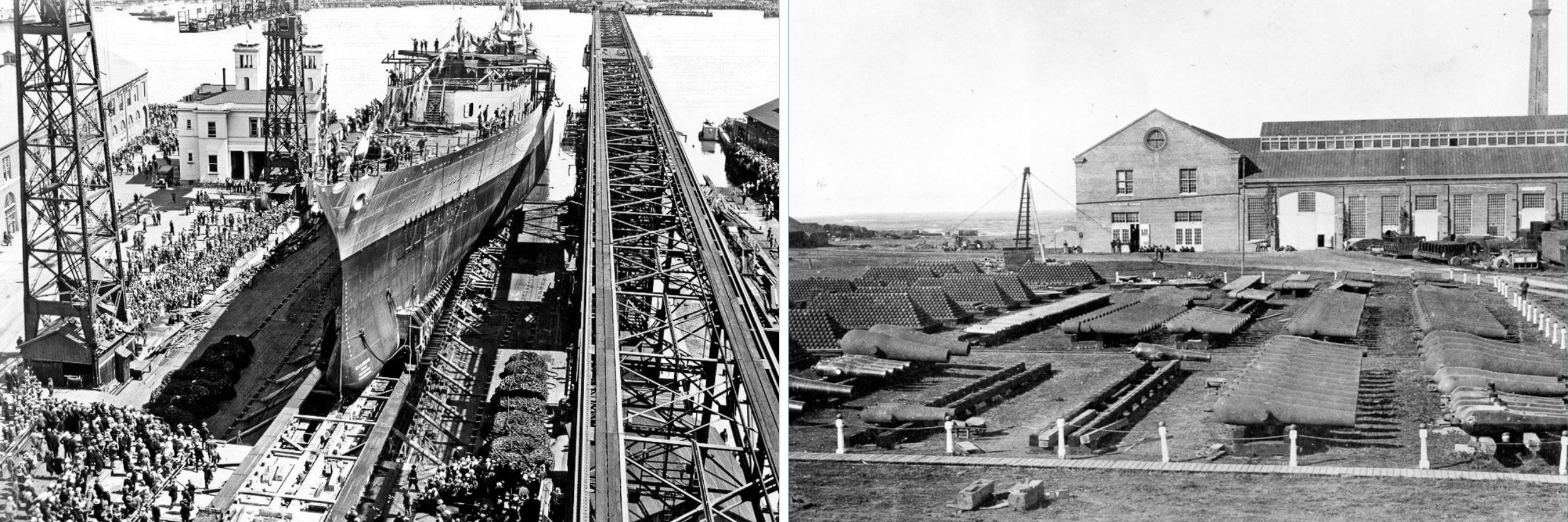

World War II was the heyday for the military in the Bay Area. Shipbuilding was a major industry and people migrated here from all over the country to take wartime jobs. The population ballooned and became more diverse. The Black population tripled in just a few years as African Americans from the South moved to the area to work for the war effort.

The Henry J. Kaiser shipyards fueled the growth of Richmond, which went from a small industrial city to more than 100,000 people, Walker said. “It just grew like a mushroom.”

And Bay Area shipyards were some of the biggest employers of women defense workers in the U.S. More than a quarter of Richmond’s shipyard workers were women.

Mare Island in Vallejo was once one of the largest Navy sites in the world — more than 100,000 people built and repaired ships there in the 1940s.

In the decades after World War II, Bay Area bases supported two more Pacific wars — the Korean War and the Vietnam War.

“I still remember my first day [on Mare Island] because I came from a small town in Michigan,” said Dennis Kelly, who started working at the shipyard in 1974. “You walked down to the waterfront and there were just people going everywhere on bicycles, cars, trucks, cranes.”

Kelly was a nuclear engineer on the base, helping to refuel nuclear-powered submarines.

“I liked the complexity of the ships,” he said. “They were probably some of the most complex things ever built by man.”

But in the 1980s, the nature of international conflict was changing. The Cold War with Russia was ending. The federal government wanted to shrink its defense budget and restructure the armed forces. That meant closing many bases nationwide — a thorny political issue. Closing any given base would mean laying off a sizable portion of a community and cutting off stable federal funding.

Federal officials created the Base Realignment and Closure Commission (BRAC), an independent body of experts tasked with determining which bases should close.

There were several waves of BRAC closure decisions between 1988 and 1995. As a result, 30 major California bases closed, accounting for more than half of the laid-off military personnel nationwide. To many, it seemed California was dealt a heavier hand than the rest of the states.

By the mid-1990s, the Bay Area military base presence was nearly wiped out entirely.

Punishment for left-wing politics?

Mare Island, which had been building and fixing warships for 150 years, was one of the Bay Area bases closed in 1996 as part of the BRAC process. Its closure had wide-reaching economic impacts on Vallejo that are still felt today. And more broadly, the base closures meant about 45,000 people in the Bay Area lost their jobs.

“Why did the Bay Area get targeted? It’s clearly political,” said Kelly, who said the BRAC process was just for show. “The analyses were cooked up to support the decision and that was the end of it.”

Kelly and others said congresspeople at the time — Diane Feinstein, Barbara Boxer and Ron Dellums — didn’t fight to keep bases in the Bay Area.

But people often cite another reason for the closures — that San Francisco was being punished for its left-wing, anti-military politics.

In the 1980s, there was a high-profile, ongoing political dispute after San Francisco officials voted not to homeport a massive battleship called the USS Missouri in the Bay.

“It was a very clear message back to Washington, ‘no, we don’t want your battleship; we don’t need the military,’” said author and historian Elouise Epstein, who did her doctoral research about the Bay Area base closures.

But Epstein said it’s too simplistic to pin all the military closures on politics.

“The bases were closed because they were out of date,” she said. “They had fundamental issues. There [were] economic problems, environmental problems and so forth.”

As the population of the Bay Area expanded, housing was scarce and expensive for soldiers. And military operations caused tensions with civilians. Alameda residents complained about the noise at the neighboring Naval Air Station. The Oakland airport was expanding and adding flights to serve the growing city. It became harder and harder for military planes coming in and out of the East Bay.

Also in the ’70s and ’80s, state and local governments started requiring the military to follow environmental protection laws, making it more costly and difficult to operate bases in the Bay Area.

“The Navy was by far the biggest polluter in the Bay Area,” Epstein said. “Civic activism really took on the military and pushed them to do the right thing, which then, of course, created more cost and more complexity, which made it harder to run these bases.”

Also, military technology was evolving, transforming the very nature of war. Maybe at the turn of the 19th century, physical forts — with cannons pointed at the bay — were best practice, but after World War II, the military used radar, satellite and thermonuclear weapons to protect the coastline.

“[The military doesn’t] want to maintain old weapons,” Epstein said. “You don’t want to maintain a tank from 30 or 40 or 50 years ago.”

Lastly, in the 1980s, the computer age began to take off and Silicon Valley was at the center. With new jobs and industry springing up, the Bay Area wasn’t as reliant on the federal government for jobs.

“In aggregate, there’s not a huge political or an economic need for the bases anymore,” Epstein said.

However, not all communities were able to bounce back after the closures. Black residents of Hunters Point protested in 1973 when their shipyard was slated for closure. Most of the people who lost jobs there were African American. Vallejo was also hit hard when Mare Island closed. “Vallejo basically grew up around the shipyard,” Dennis Kelly said. “Vallejo ultimately went bankrupt and it still struggles today.”

Almost 30 years later, Mare Island is starting to develop a new identity with new homes and businesses opening. It has taken many decades, but the former military base may one day be a different kind of economic boon to the local community.

For more on the opportunities and challenges of redeveloping former military sites, read part two of this series.