Hoover is referring to California’s power grid and the state’s mandatory transition to 100% carbon-free energy by 2045, under a 2018 measure. California has made significant strides toward the target but scores a low D- rating for its resilience to extreme weather events and other disruptive threats, according to measurements by the nonprofit Grid Clue. Despite an ongoing shift to renewables, California is still heavily reliant on fossil fuels, and its grid is increasingly under peril because of wildfires, heat waves, and other weather events linked to climate change.

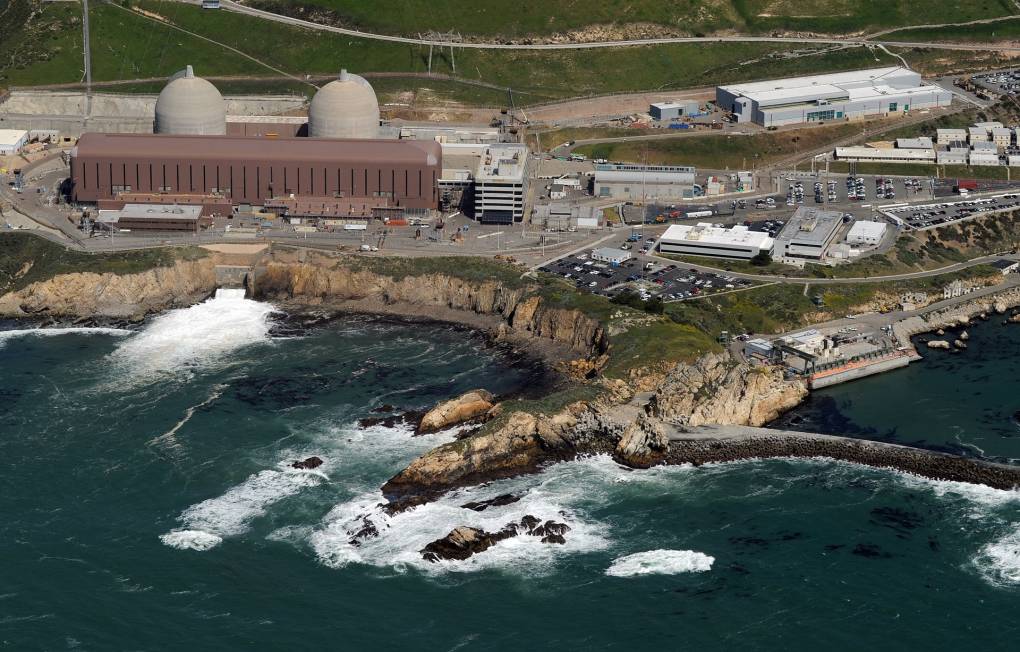

Diablo Canyon provides roughly 9% of the state’s electricity, which is partly why Gov. Gavin Newsom supported extending the use of its reactors to 2029 and 2030. “That struck me as a courageous decision and the right decision, and I would hope that that’s reflective of his belief to look at all different energy sources,” said Republican Assemblymember Diane Dixon, who represents Newport Beach.

Representatives for PG&E, which owns and operates Diablo Canyon, have typically adopted a defensive posture when asked about their nuclear facility and the cost overruns it routinely incurs. But the utility company has been singing a different tune lately.

Zawalick, the PG&E vice president, demurred when asked if she thinks Diablo Canyon will ultimately stay open past the station’s latest deadline. “We have to be asked by the state legislators to go longer than 2030,” she said. “But we will be ready, is what I say. And we’re planning to be.” She told CalMatters she hasn’t had any “formal” conversations with tech companies about Diablo Canyon’s future.

Stern described Diablo Canyon as a “cost-suck” and “old,” adding, “If you were building new nuclear, you would not build it like Diablo Canyon.” But Stern conceded that San Onofre’s shutdown strained the state’s energy grid (it also led to more greenhouse gas production), and he’s come to accept Diablo Canyon’s role, at least for now.

Democratic Assemblymember Joaquin Arambula, who represents Fresno and has co-sponsored nuclear energy legislation, also worries “about what would occur if a member of our energy portfolio was taken offline, how that would increase rates for the rest of us.” Hoover echoed Arambula’s view and said he wants Diablo Canyon to stay open indefinitely.

An opening for small modular reactors

Diablo Canyon is one (complicated) piece of the nuclear puzzle. Then there’s the separate conundrum of whether to roll back all, or some, of the state’s nuclear energy moratorium. As it stands, Republican lawmakers are the political faction that has pushed to change the moratorium. Last year, Dixon was a cosponsor of Assembly Bill 2092, which would’ve asked the California Public Utilities Commission to conduct a feasibility studies about the possible benefits and effects of small modular reactors by the beginning of 2027. The bill never got a vote on the Assembly floor.

“It’s good to have stretch goals,” Dixon said of the state’s zero emissions target. “But we have to be mindful of the impact on the local economy, on jobs, and driving businesses out of California. I want to at least start the process to study this important possible new alternative.”

Another recent proposal, Assembly Bill 65, would’ve created a moratorium exemption for the development of small modular reactors. Hoover and Arambula were co-sponsors on AB 65, and Arambula said he hopes to introduce a similar measure in the 2025–26 legislative session.

In April 2023, the last time lawmakers debated the bill to allow small modular reactors, Arambula was one of few Democratic politicians to publicly back pro-nuclear legislation. Los Angeles Democratic Assemblymember Rick Zbur, for instance, told his colleagues he couldn’t support the measure because, while he “used to be someone who believed that nuclear was part of the solution to a carbon-free future,” he changed his views after the 2011 nuclear power plant disaster in Japan. “I don’t think that the California public supports this,” he continued. “I don’t think that we need this to get to a carbon-free future.” (Zbur confirmed to CalMatters that his stance hasn’t changed of late.)

Other prominent Democratic politicians are beginning to sound more bullish on nuclear energy sources. Democratic state Sen. Scott Wiener of San Francisco told CalMatters that he’s noticed “a gradual increased openness among Democrats to nuclear,” and that he thinks nuclear “should certainly be part of the conversation.” Stern, the Senate environment committee member, said he’s interested in giving consideration to some nuclear power bills.

Stern previously authored a law that required the California Energy Commission, in consultation with other state agencies, to write an assessment of commercially feasible energy sources. That assessment, which was released in August 2024, suggested more research and development into small modular reactors and recommended that the legislature pass a law to exempt such reactors from the state’s nuclear moratorium.

In a statement, Newsom’s office left the door open to the possibility of small modular reactors and a nuclear moratorium exemption in California. “The Governor has always maintained an interest in new, promising technologies, including advancements in emerging nuclear power technologies, that follow strong safety, cost, and environmental considerations,” Newsom’s Deputy Director of Communications Daniel Villaseñor wrote to CalMatters.

State Sen. Josh Becker, the new chair of the Senate Energy Committee, also left the door open to nuclear technologies in California: “Climate change is an urgent crisis demanding a comprehensive and proactive response,” the Silicon Valley Democrat wrote in a statement. “To address it effectively, we must consider every viable solution.”

What happens next?

The 2025–26 legislative session will be instructive in showing state lawmakers’ willingness to embrace nuclear energy. Any policy changes in California — followed by a hypothetical nuclear site selection process — would proceed at a slow, methodical pace, the exact opposite of how tech companies prefer to operate.

In addition to needing to get a carve-out from the state’s nuclear moratorium and approvals from various state and federal entities, nuclear plant builders could well face lawsuits and other pushback from anti-nuclear groups.

With all those factors in mind, the legislative session will also reveal whether tech companies feel emboldened to push for nuclear energy sites in California, or if they’re satisfied pursuing their energy needs in other states.

After all, just because many key AI companies are based in California doesn’t mean their data centers have to be. The recent failed bills to permit some kind of nuclear power in California were proposed shortly before tech’s fast and furious incursion into the nuclear energy space and thus weren’t part of the industry’s 2023–24 legislative lobbying efforts. Public support and lobbying for the two bills came from a handful of relatively small pro-nuclear advocacy groups, as well as a handful of labor groups, and the Nuclear Energy Institute, a pro-nuclear trade association.

“It’s too soon to tell how serious these tech firms are about promoting nuclear energy to power their electricity needs,” Squassoni said. “It could be a fad — it could be that once they get a real whiff of the costs and time it takes to build new plants, they may back off a little bit.”

Lawmakers who spoke to CalMatters said they aren’t against tech companies joining in on broader policy debates around California’s energy grid. Hoover said tech’s nascent nuclear interest may “allow for new conversations to happen,” while Wiener characterized the industry’s involvement as a “positive thing,” so long as companies participate in expanded clean energy initiatives that aren’t exclusively nuclear.

Stern, for his part, posited that tech’s interest “certainly doesn’t hurt the zeitgeist around nuclear being a less toxic and scary thing.” He added: “There’s some other incredible tech that, in a lot of cases, beats nuclear from a cost perspective. But it doesn’t quite make sense to me anymore that we don’t let nuclear compete in that contest.”