Episode Transcript

This is a computer-generated transcript. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Olivia Allen-Price: I’m Olivia Allen-Price. And you’re listening to Bay Curious. Nowadays, if you’re eating fish out of a can, it’s likely tuna. But in the early 20th century, canned salmon was far more popular.

Advertisement Sound: Whitneys the quality canned salmon from Alaska’s world famous waters. Serve Whitney’s salmon in baked seafood salad, salmon loaf, or molded salmon ring.

Olivia Allen-Price: This advertisement for Alaskan canned salmon is from the 1950s, but the salmon canning industry has roots in California, starting in the mid-1800s.

Advertisement Sound: Whitneys, whitneys, whitneys … For a tasty dish with zing, a can of whitneys is the thing.

Olivia Allen-Price: The biggest canning companies were headquartered in San Francisco. And seasonal workers boarded ships in San Francisco to get to those Alaskan waters. There’s even a piece of this history still floating out in the San Francisco Bay!

Sabrina Oliveras: It’s not exactly a pirate ship, but if you let us tell you the story, there were some pretty nefarious things going on.

Olivia Allen-Price: Today on Bay Curious, we trace the salmon connections between San Francisco and Alaska … and learn about the early workers who made the industry possible. Batten down the hatches; there are rough seas ahead! Stay with us.

Sponsor message

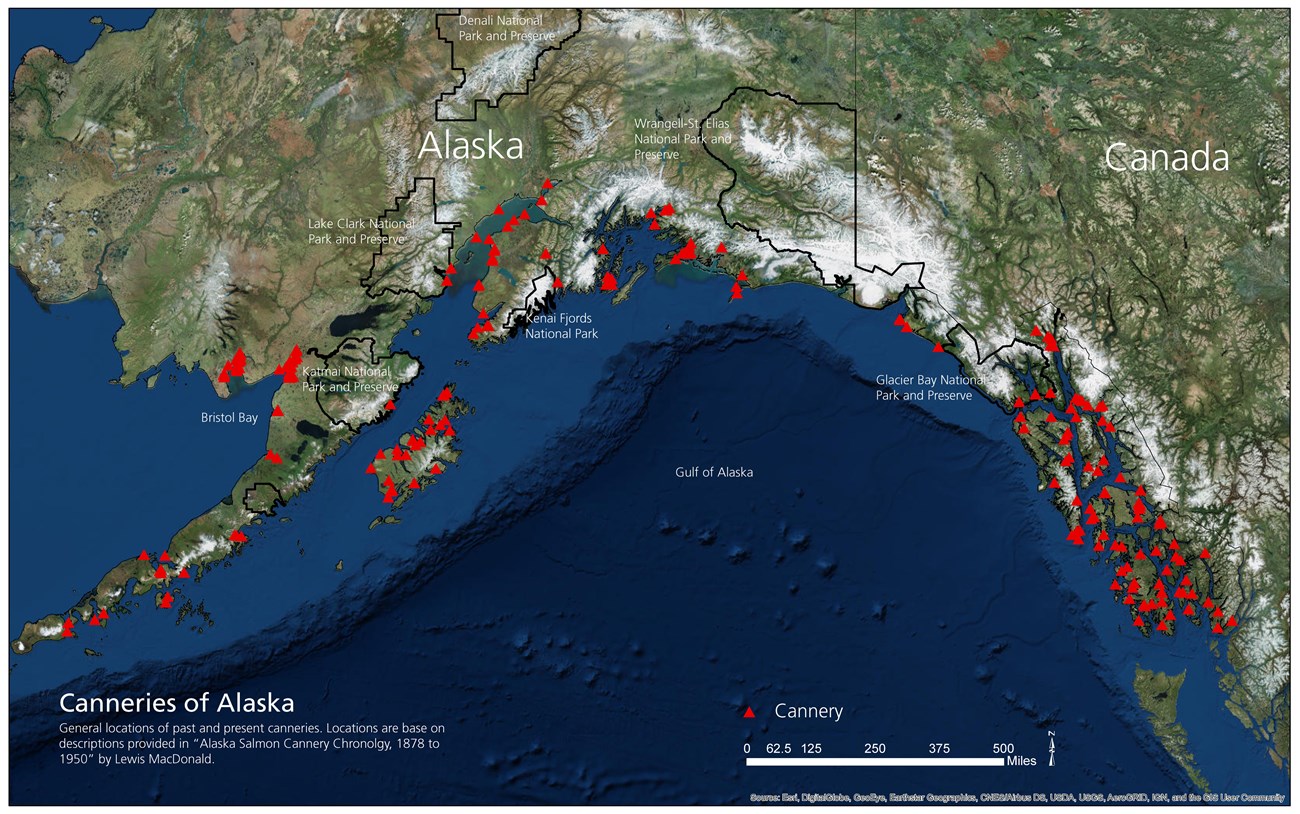

Olivia Allen-Price: Starting in the mid-1800s, Salmon canneries were big business along the West Coast, stretching all the way up to Alaska. San Francisco played an outsized role in the industry — and especially in providing the workers who did the tough, dirty, low-paid work in the canneries. Bay Curious editor and producer Katrina Schwartz starts us off in Bristol Bay, Alaska, in the 1970s.

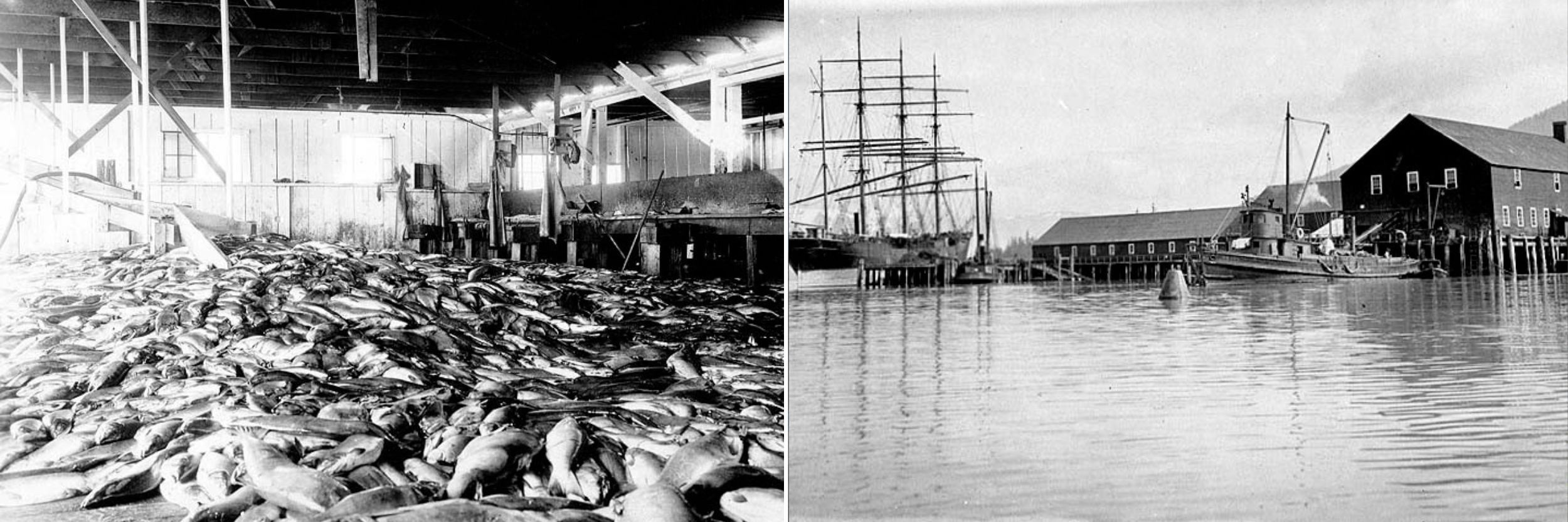

Katrina Schwartz: Imagine a stretch of marshy ground in an isolated bay. A nondescript factory built on a pier hunkers near the shore surrounded by a few low bunkhouses and a smattering of cabins. Patches of melting snow dot the ground. It’s austere. Lonely. Beautiful.

James Chiao: Such a remote place. No radio. No newspaper, no TV. So you’re totally cut off from the outside world. My name is James Chiao, and I am an immigrant. I was born in Taiwan.

Katrina Schwartz: James and his brother Philip worked at the salmon canneries in Alaska in the 1970s for several summers during college. James stood next to a machine that gutted and cleaned the salmon. A more seasoned co-worker stood next to him, pulling the eggs out of the fish. James took care of any that slipped by.

James Chiao: The salmon, the fish would come in on a conveyor belt passing, I’d say maybe 60 to 80 fish per minute. So they were flying by.

Katrina Schwartz: James would stand there clad in tall rubber boots and full rain gear, water flushing the fish carcasses down a conveyor belt, sometimes working a 16- or 18-hour shift.

James Chiao: It was noisy. There’s water and blood everywhere.

Katrina Schwartz: He says it was mind-numbing, repetitive work, but he didn’t mind. It was a nice change of pace from studying. The scenery in Alaska was fantastic. And the money was good.

James Chiao: When I was attending University of Washington, the tuition was probably over $1,000 a year. And I was able to make in two months enough money to pay my tuition.

Katrina Schwartz: James remembers that time fondly. It was a unique experience, but not his real life. He went on to become an electrical engineer. And when he retired a few years ago, he began reflecting on his life, thinking back to those summers in Alaska in the ’70s. And he started to do a little research about the salmon canning industry, which dates back to the 1860s. He was interested to learn he wasn’t the only immigrant to find themselves canning salmon in Alaska. Far from it.

Music

James Chiao: I think we should go back, you know, to the Hume brothers.

Katrina Schwartz: Brothers William and George Hume were fishermen originally from Maine. They moved to California, like so many others, to seek their fortune. When they arrived, they started catching and selling salmon. Now, these were the days before electric refrigeration was widely available … so they sold the salmon either fresh caught or preserved in salt. So when their buddy from Maine, Andrew Hapgood, moved out to California and brought materials to can and preserve fish with him, they knew they had a good business idea.

James Chiao: In 1864, they founded the first salmon cannery in on the Sacramento River.

Katrina Schwartz: It didn’t take them long to realize runoff from mining was killing the salmon. So they moved their operations to the Columbia River in Oregon. The Humes, who were white, hired 12 Chinese workers to do the canning.

James Chiao: He found their work satisfactory. Better than his other workers.

Katrina Schwartz: The Transcontinental Railroad was almost complete, and Chinese laborers who had immigrated to the U.S. were looking for more work. The Hume brothers hired them through the same contractors who found workers for the railroads and paid them a similarly low wage. Other salmon cannery owners along the Columbia copied the Humes business model.

James Chiao: Almost like it become the success formula. Look, if you want to be successful, you need to have the capital. You need to have the technology. How to make the cans. And number three, you need Chinese workers.

Katrina Schwartz: James says by 1874, there were 13 canneries along the Columbia River and 95% of the cannery workers were Chinese. Pretty soon, the Humes, and most of the other cannery owners, moved their operations to Alaska, where the really big salmon runs were. San Francisco was the biggest city on the West Coast. Everything flowed in and out of its seaport.

James Chiao: The components are all in San Francisco.

Katrina Schwartz: The fishermen and cannery workers. All the supplies and provisions needed for the trip. And, of course, the vessels that carried it all to Alaskan waters. The Hume brothers’ company joined up with several other big canneries to form the largest salmon canning company, the Alaska Packers Association. It was headquartered in San Francisco and shipped canned salmon all over the world.

Sound of creaking of ship

Sabrina Oliveras: We are we are right now around the main deck of the Balclutha/Star of Alaska, right under the main mast. My name is Sabrina Oliveras, my title is Park Ranger Interpretation Exhibits and I work at San Francisco Maritime National Historical Park.

Katrina Schwartz: James and I meet Sabrina on board the Balclutha … a sailing ship built in 1886 … and known as the Star of Alaska when it sailed as a cannery vessel. It’s one of the best physical reminders of the salmon canning trade still floating in the Bay. It was on a ship like this that salmon cannery workers would begin their long journeys. The Star of Alaska was strictly divided based on social class and occupation.

Sabrina Oliveras (giving tour): So right now, we are where we call the Captain’s Saloon.

Katrina Schwartz: The captain’s quarters are at the far back of the ship, where the rock and sway of the ocean is less noticeable. He would have had a private bedroom, bathroom, pantry and sitting room.

Sabrina Oliveras: This also was where a captain would hold office while in port. So you know he’d have to like entertain other merchants or captains or ship owners and all that, which is why it’s nice, and it has a skylight, detailed glasswork.

Katrina Schwartz: Beautiful hardwood floors, plush seats.

Sabrina Oliveras: Yeah, plush seats.

Katrina Schwartz: Towards the middle of the ship, but still on the same level, were the fisherman’s quarters.

Sabrina Oliveras: The fishermen for Star of Alaska would have mostly been Italian or Scandinavian men, you know, living and working in the Bay Area.

Katrina Schwartz: There were about 80 of them, and they were unionized workers for the Alaska Packers’ Association. They also acted as the sailors on the month-long journey up to Alaska.

Sabrina Oliveras: There’s probably like over 10 portholes that you can open.

Katrina Schwartz: Portholes mean there was sunlight and fresh air. Once the ship arrived in Alaska, the fishermen would be in charge of catching the salmon. But the canneries also needed people to butcher, chop and can the fish.

Sabrina Oliveras: There would have been anywhere from 100 to 300 cannery workers who were transported on ships like this going up to Alaska, and they came back down on the same ship. They would have lived below decks in the area. We now call the tween deck

Walking downstairs

Katrina Schwartz: To get there, we take the stairs, thoughtfully installed by the park for visitors. Back in the day, the cannery workers would have used a ladder only about a foot-and-a-half wide.

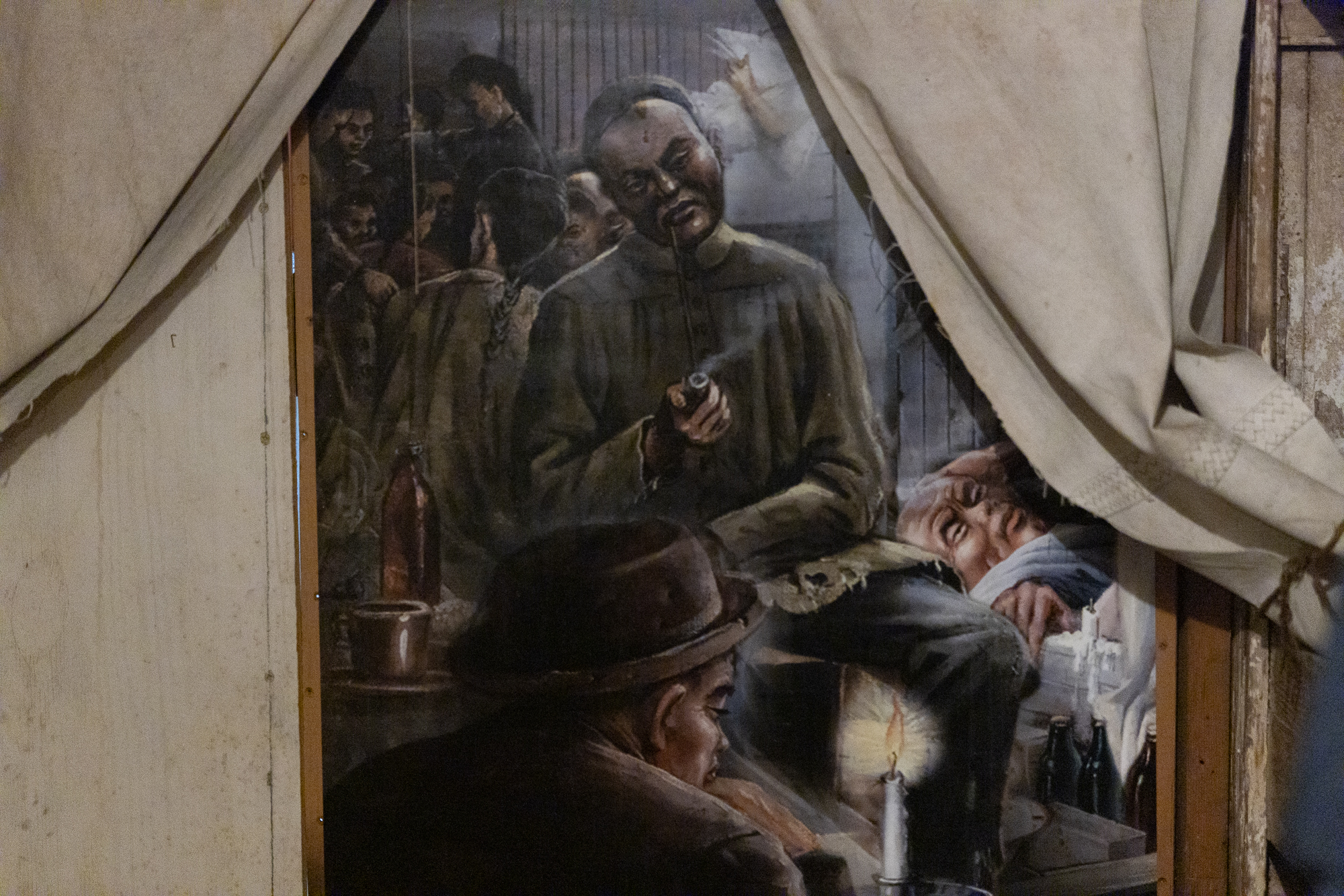

Sabrina Oliveras: We are looking into an area where on either side of us, there are three levels of bunks. This is a representation of what they called at the time the Oriental Quarters or in some sources they call it Chinatown.

Katrina Schwartz: The space is cramped. The bunks short, with not even enough room to sit up.

James Chiao: To me, this is amazing. I’ve never thought of someone stay here in this kind of condition for over four weeks, right? Takes about 30 days, 33 days to travel from San Francisco to Bristol Bay.

Katrina Schwartz: James says when he went to work in the Alaska canneries, he could travel there in one day.

James Chiao: This place is so hot. And also, there’s no ventilation. And there’s no electricity. OK, we have a light here. So it was lit by candles or lamps. It’s just totally, you know, it’s not a very good experience.

Katrina Schwartz: Unlike the fishermen, who were mostly white, the cannery workers were not employed directly by the Alaska Packers Association. Instead, they were hired by independent labor contractors.

Sabrina Oliveras: The APA really just let the labor contractors do what they want, essentially, which is why they had so much power and there was so much opportunity to exploit. Because the APA would just say, you set the terms, we just want so-and-so amount of crates delivered at the end of it all.

Katrina Schwartz: At least two primary sources describe being forced to pay for passage on the ship, for specific clothes that often weren’t necessary, and for bedding as a condition of employment.

James Chiao: A lot of them were, you know, they spent so much money on their clothing, on outfit, and then there’s also gambling, and also they have to pay some of the canned food. So, usually, by the time they come back to San Francisco, all those money were subtracted off of their wages. So they have very little left.

Katrina Schwartz: Sometimes, workers would end the season in debt to the labor contractor, ensuring they’d come back for the following year.

Music

Katrina Schwartz: And so these ships, laden with men and supplies, would sail out from San Francisco and make their way to remote, wild southwestern Alaska every summer. One of the most detailed first-person narratives comes from Max Stern, a white newspaperman who went undercover on assignment as part of the so-called “Chinese Gang” in 1922. It didn’t take long for him to feel the pain of being in the lowest social class on the ship.

Voice reading the writings of Max Stern: I was sweating from the heat of my companions, I was seasick, I was vermin-covered, and I must admit, I was downright homesick.

Katrina Schwartz: After arriving in Bristol Bay, the first task in the cannery was to turn the metal they brought with them into cans.

Voice reading the writings of Max Stern: My job was testing cans. I would stand over a little tank of hot water, place a finished can into the basket, and with a foot lever immerse it. If there were any leaks, bubbles would appear.

Katrina Schwartz: In the late 1800s, decades before Stern was on his undercover mission, skilled Chinese butchers would spend long hours butchering, cleaning, cutting and processing the fish. Sabrina says a skilled worker could remove the fins, head, tail and entrails of three fish per minute. But around 1903, times were beginning to change.

Music

Sabrina Oliveras: This machine, it is a central artifact of this exhibit.

Katrina Schwartz: Back on the Star of Alaska, Park Ranger Sabrina shows us an 8-foot tall, massive iron contraption. Now called a “salmon butchering machine,” it was known by a more racist name when it was invented.

Sabrina Oliveras: It was designed to start replacing human labor. The earliest versions of the salmon butchering machine could have done like 50, 60 fish in a minute. So as you can imagine, like this machine was welcomed by the industry for a variety of reasons, one of which was, you know, he needed to keep producing more and more.

Katrina Schwartz: Cannery owners were eager to replace the workers who had made the industry possible. James Chiao again.

Jim Chiao: Even in their advertisements, they said they wanted to replace all the Chinese Butchers. And by the 1920s and ’30s, it did.

Music ends

Katrina Schwartz: By this time, the industry was feeling the effects of the Chinese Exclusion Act. Chinese labor was harder to find, and many roles were replaced by other Asian immigrants. First, Japanese … and later Filipino folks. Farmworkers in California would finish up the spring harvest and head to San Francisco to hop on a salmon boat bound for Alaska. When the summer fishing season was over, they’d return to California for the fall harvest.

Sabrina Oliveras: Which is why eventually, in the 1930s, when they started unionizing, it wasn’t just a cannery workers union; it was a canary workers and farm laborers union.

Katrina Schwartz (during interview): Wow, because it was the same folks.

Katrina Schwartz: Once the union came in, there was less opportunity for labor contractors to exploit workers, and conditions at the canneries improved. James Chiao says he benefited from those changes by the time he arrived in Alaska in the ’70s.

James Chiao: In general, I thought it was it was okay. It was decent.

Music

Katrina Schwartz: Much of the salmon we eat is still caught in Alaska, but canning isn’t the big business it used to be. The Alaska Packers Association eventually became part of the Del Monte conglomerate, which sold its last canneries in the early 1980s.

James Chiao: Oh yeah, there’s a huge change in how they process the salmon, how they just freeze the salmon and ship it to the supermarkets directly. So now, the canned salmon is no longer really something that we are familiar or used to. That’s a big change.

Katrina Schwartz: James says even in the ’70s, when he was working in Alaska, cannery workers rarely tried the product.

James Chiao: In the mess hall, we never got to eat salmon. So, many years later, I went to the grocery store and tried canned salmon. My goodness, it was no good! (laughs)

Katrina Schwartz: These days — few signs remain of the once booming salmon canning industry in San Francisco. Most of the companies have been sold off or moved elsewhere. But for James and the National Park Staff overseeing the Star of Alaska — the hard work and sacrifice of the workers who once kept them running hasn’t been forgotten.

Music end

Olivia Allen-Price: That was Bay Curious editor and producer Katrina Schwartz. Head to BayCurious.org to see photos from our trip to the Star of Alaska, plus archival photos from San Francisco’s salmon canning history. We’ll drop a link in our show notes, too.

I love episodes like this one … they open my eyes to something about the Bay Area that … frankly, I had no idea about. That’s one of our big goals here at Bay Curious, actually. And if you think we’re the mark, please consider leaving us a rating or a review on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or wherever else you might listen. Kind words keep us going and help other potential listeners find our program. It only takes moment, and we really appreciate it. Thanks!

Bay Curious is made in San Francisco at member-supported KQED. Our show is produced by Katrina Schwartz, Christopher Beale and me, Olivia Allen-Price. Extra support from Katie Sprenger, Maha Sanad, Alana Walker, Jen Chien, Holly Kernan and the whole KQED Family.

Some members of the KQED podcast team are represented by The Screen Actors Guild, American Federation of Television and Radio Artists. San Francisco Northern California Local.

I hope you have a wonderful week.