This is an updated version of a post that KQED first published in April 2012.

Time to replace that exclamation point with a period.

After a torturously slow decline, Yahoo!, finally, is done.

And who can say, in the decades to come, whether the name will survive as even a historical footnote?

But it wasn’t always this way. There was a time — back in the waning years of the last century — when Yahoo! could do no wrong. And as the undisputed King of the Web, the company’s skill in navigating the “New Economy” combined with an irrational stock market to make a sizable number of employees wealthy.

I was one of them.

1996

I‘m standing outside Yahoo! headquarters in Sunnyvale, after an hour-and-15-minute drive from my home in San Francisco. Until this moment, I have tooled around the World Wide Web for a total of perhaps 45 minutes in the aggregate; my modem is so slow it takes about five minutes to download a single page. But a recommendation from a former colleague who now works for the company has landed me a job at a reasonable salary, a welcome rise from my previous year’s income of $12,000 earned at several part-time jobs.

As I step for the first time into the purple-and-yellow Yahoo! lobby, two thoughts occur:

What’s with the exclamation point?

It sounds an awful lot like Yoo-Hoo.

At the orientation, the HR lady says I’m employee No. 109 — that’s 107 employees removed from Yahoo! founders David Filo and Jerry Yang. At some point, the words “stock options” are mentioned, and the other new hires perk up.

“This is what you’ve been waiting to hear about, right?” the HR lady says. Actually, I have no idea what those are. I want to hear about the insurance — I haven’t been to the dentist in five years.

Welcome back to the middle class, I think.

1997

There are two classes of people at Yahoo!: the pre-IPOs, and everybody else. The pre-IPOs became overnight millionaires, or close to it. The rest of us have to wait a year before a quarter of our stock options vest and we can cash in. The pre-IPOs drive Porsches, Jaguars, BMWs. I drive a Ford Festiva, a vehicle the “Car Talk” guys say “should come with its own funeral wreath.”

The disparities play out interpersonally. One of the early engineers offers $1,000 to a new employee to eat an entire bottle of ketchup at a restaurant, a proposition that was readily accepted.

I am waiting for the stock to crash, as many a knowing analyst predicts it will. Yahoo! is a company that is barely profitable –- it’s trading at hundreds of times earnings, and I am certain the mass irrationality will burn itself out before I get to benefit.

But the quarterly reports show progress, and the market reacts each time with extreme enthusiasm. “It’s revenue that’s important at this point, not earnings,” a co-worker tells me. Sure, what do I know.

Despite the success, Yahoos are frequently tense. There are many turf wars. The world seems to think the Web will be the dominant business in coming years, and that Yahoo! will be the dominant company in that dominant business. So those who dominate within the dominant company in the dominant business will thus dominate Everything. Paradoxically, when you’re told something is going to get bigger and bigger, there doesn’t seem to be enough to go around.

Meanwhile, I enjoy the free bagels with lox and the complimentary health club membership, which gives me access to indoor and outdoor pools, a sauna, tennis courts, basketball courts and enough free towels to mop up Lake Merritt. The faux pond in the spacious lobby is not to my taste, but seems in keeping with a general disregard for any lifestyle that might be termed “natural.” (One day I decide to take a walk outside the office, only to find after a few blocks that the sidewalk has disappeared.) In the men’s locker room, there’s a lot of talk about the stock market. Apparently, it’s a pretty good way to make money.

1998

The engineers are everything. If they buy into your project, you’re golden. If they don’t it’s going to die on the vine, like “Yahoo! Pets” or some other godforsaken property that consists of the company name, a noun and some links.

“It’s on the list,” is something you hear a lot from the programmers when you want them to add a feature or fix a bug. The thing is, nobody really knows how long the list is or exactly what’s on the list or if there even is a list. Nobody except the engineers.

I buy a new car, a Volkswagen Beetle. My engineer tells me, “That’s a chick car.” I laugh — I need him to tweak something on my site.

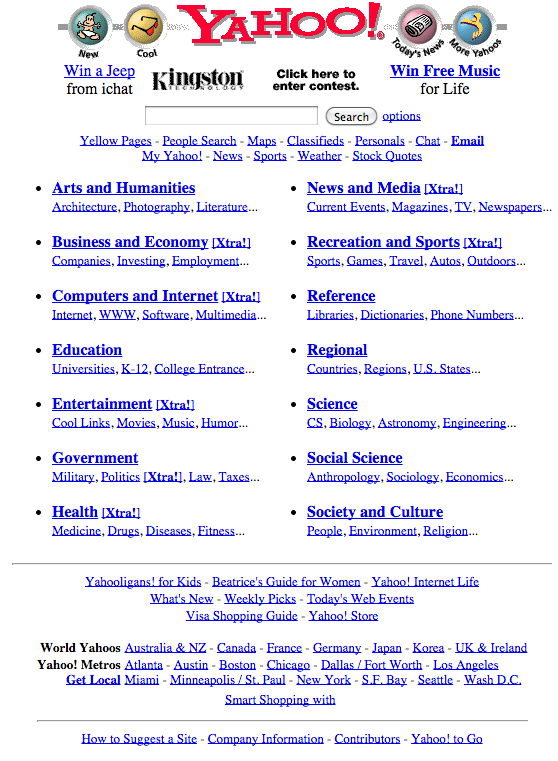

The engineers seem to have a soft spot for editorial people like me, even though we’re at the bottom of the status pile, officially classified by the company as “surfers.” (“Yahoo! Surfer” is actually on my business card.) Most surfers categorize websites for Yahoo’s massive directory, which takes up most of the space on its front page.

Who the engineers really can’t stand are the “producers,” the people who are being brought in by the SUV-load to transition Yahoo! from a company that simply links to other websites into one that offers content of its own, through partnerships. The engineers don’t like the producers because the producers want to systematize the way projects get done, thus cutting into the computer whizzes’ autonomy.

Despite these internal battles, Yahoo! is decimating competitors, companies like Excite! (also with an exclamation point), Infoseek and the unfortunately named Lycos. The Yahoo! softball team even defeats Excite! in a softball game in which Excite! has recruited Barry Bonds to play in a paid promotional appearance. Yahoo! likes to say it prevails because of the “human touch,” the intercession of editors who organize the exponentially growing number of websites into manageable categories. The also-rans, they’re strictly algorithmic –- and robots can’t beat human beings.

Personally, I think Yahoo! is taking no prisoners because of David Filo, the company’s laconic, near hermitic co-founder. The face of the company is Jerry Yang, but internally many people don’t now know, exactly, what it is that he does. Filo, on the other hand, is a legend bordering on myth, infrequently seen outside his cubicle, which he shares with another engineer. I’m there about a month before I have my first Filo spotting — he’s playing foosball in the breakroom. “Who’s that?” I ask someone. Filo wrote the original program that allowed surfers to input a URL that can generate into an HTML page. Without that, you’d have to hand-code everything. It’s Yahoo’s secret sauce.

Filo also controls the front page and has a keen editorial sense. One day he emerges from his lair to talk to me about our news product, which I work on, for an unbelievable 45 minutes. I can feel the eyes of the room on me, and they’re not burning with admiration. “Wow, you got some serious face time with Filo,” says a co-worker, bitterly.

At a certain point, the word Yahoo! is on everyone’s lips. (In 2000, the success of the company will be a key plot development in the sci-fi movie Frequency.) Every time I mention where I work, people get this warm look on their faces, either because they use it and love it or they’ve made a lot of money on the stock.

Doctors are the most prone to dot-com fascination, I find. They seem to know every little nook and cranny of the internet “sector” and can’t seem to stop talking about the price of Yahoo! shares. They can even throw around metrics like “page views” and “eyeballs.” It’s the doctors who also seem to be the most offended by the financial windfall the 20-somethings — most of my colleagues — have stumbled into.

“It’s disgusting,” my internist says. Hey, I don’t make the rules. You should’ve worked at a bookstore or a library — where most of Yahoo’s early employees came from.

1999

Yahoo! shares are going in three directions: up, up and up. Yahoos are literally giddy, reloading the stock price on Yahoo! Finance 10 to 20 times an hour. “Hey it’s at 150! Now it’s at 175!” A lot of Yahoos are so young they’re working their first or second job out of college. They don’t seem to understand that the system of American reimbursement for employment doesn’t really work like this. Not usually.

The company is awash in other people’s money. It has split its stock several times, but we Yahoos want them to do it again. “If we split the stock, the price will just go right back up to where it is now,” CEO Tim Koogle tells us at a company meeting. He says it like it’s a bad thing. But the rank and file – they want more shares. Because it’s never gonna end –- people are buying houses with all cash. Taking flying lessons. Investing in art. My co-worker, a 20-something who has adorned her cube with miniature knick-knacks and kitsch, who just a few years before would most likely have had to put time in at a coffeehouse or temp firm, buys two houses. Plus, literally, a mansion, back in her hometown.

In April, I tell my mother how much I pay in taxes and am immediately sorry. It’s not that she’s going to let the amount casually slip to friends, it’s that she actually gets on the phone to tell them.

Naysayers, however, cloud the horizon, however dimly. “In a bear market,” says one rare CNBC party poop, “stocks lose 95 percent, 98 percent, 99 percent of their value. This generation has never experienced a bear market, but things don’t go up forever.”

Yes they do. Nothin’s gone down yet. “It’s the 401ks,” my friend’s father tells me. “You never had this automatic investment in the market before, that’s why it’ll keep going up.” Exactly, I reason. I read the take of one analyst in the New Economy bible, Red Herring. He says if you really want to own a stock, “the purchase price doesn’t matter.” That periodical — it’s a must-subscribe. I buy some Amazon.com; it takes about a week to double. Then I sell it, only to see it double again a few days later.

“I want to buy some Yahoo! stock,” my father tells me over the phone. “What do you think?”

“Some people say it’s overvalued.”

“I’m gonna buy some Yahoo stock,” he amends, turning his question into a statement. He has never been on the internet. Once, in all seriousness, he called it “the Intercom.”

Around this time, a co-worker tells me about a search engine that actually seems to work. Oh man, they even copied our infantile double-vowel sound, I think as I surf my way for the first time onto Google. But Yahoo! Finance, Yahoo! Sports, Yahoo! News, Yahoo! Mail — who can compete with those? Google — sounds like another also-ran.

Meanwhile, my fellow surfers are busy building the Yahoo! directory by way of long and emotional debates. “Shouldn’t this live in the Anthropology category and not Archaeology?” someone writes, starting a seemingly endless thread of sincere and thoughtful emails about the merits of such a proposal. “I’m creating a category for 18th century military history — anyone object?” Yes, someone does.

One day, a naive soul sends out an email: “Don’t you think most people don’t use the directory anymore, just type in what they want in the search box?” A dead mass silence ensues, as if someone has knocked the exclamation point off the end of the company name and replaced it with a question mark.

2000

A predicted technological apocalypse, the “Y2K problem,” does not occur, and the market reacts by going up, up, up in what’s described as “panic buying.” Unwisely, I have been sitting on the sidelines, but now I pour a whole pile of money in– gotta get on that bus before it becomes a jet plane.

Make that a rocket. By March, my net worth, much of it on paper, exceeds all the money my mother and father have made in their entire lives.

But things aren’t going that great at work, and I want to quit. Problem is that would leave a big pile of options on the table. People are begging me not to do it. “People work their entire lives to be in your position,” a 65-year-old friend tells me.

Someone I meet who will never be in my position is the guy who rings up my coffee every morning at the Chevron station. It’s just one of three jobs, he tells me — that’s the only way he can send his son to Stanford.

I decide to stay. The market decides to crash.

“It’ll go back up,” people reassure each other. “It always does.” And it’s true, we’ve experienced false alarms before, most notably during the 1998 Asian currency crisis, which temporarily put a damper on the fun, but which dutifully ended only to see shares rebound to even higher levels. “You sell too soon,” my friend, who has just bought the first house he looked at, tells me. “You have no faith.”

Later

“I was just waiting for it to get back up to 200,” one early Yahoo! informs me, referring to the stock price, which is now somewhere south of 20 after the worst stock crash since the one that touched off the Great Depression. This person, in his four years at the company, has sold virtually none of his shares. “I just thought it would be something for the future,” he says.

The guy who told me I sell too soon now says he may lose his house.

There are worse stories, too. There’s a little known or at least little understood provision in the tax code that stipulates if you buy your options and then hold onto the shares, which people do in order to reduce their taxes, the tax obligation is the same as if you actually sold them. This will lead to people actually losing money on the transaction if the stock drops while they are holding onto it. Tales of extreme woe along these lines abound.

As for me, it was always: Which will make me feel like the bigger schmuck — if I sell and then it stock goes way up, or if I hold onto it and it goes way down? Since no one can predict the future, that’s the only variable to consider.

Even later

What once seemed like all the money in the world, I find, turns out to be decidedly finite after all. My plan to sleep in followed by a little TV followed by a nap did not take into account a daughter, a mortgage, the exorbitant price of individual health insurance and a worldwide financial crisis. The Yahoo! options my wife still owns plenty of are perpetually underwater –- no help there. Circumstances force me to procure some contract work, which sends me back to Yahoo! But eventually I am … laid off.

And I really need the money.

Welcome back to the middle class, I think.