Last year, BSG’s executive producer Ronald D. Moore spoke at the Hero Complex Film Festival in Los Angeles about watching the original series pilot in the months after 9/11 and re-imagining it for a 21st century audience:

“I just realized, immediately, that if you did that show in that moment in time, the audience could not help but bring their experience with them. And if you did a show, you had an opportunity and a responsibility to talk about what we were going through as a culture and what was going on in the world… and to ask hard questions and not really deliver neat answers every week.

I always thought there was a kind of egotism to the idea that a show of television could [say] ‘Well, here’s how Al-Qaeda could be dealt with, and here’s the answer to Iraq, and here’s the answer to terrorism.’ It was important to me that the show just asked you questions and challenged your assumptions, and if you came out of the end of that experience with your beliefs confirmed, fine. And if you came out the other side with your beliefs challenged, that was great too. I just wanted you to think for 45 minutes.”

9/11 was so awful, so unexpected, yet understandable in retrospect. The only equitable response was to raise the questions of why it happened, how it happened, and what we do now. Battlestar Galactica, from 2003 until 2009, explored the immediate aftermath of trauma, grief, and who we choose to be and who we turn to when we fall down. It looks like it’s about robots, war, and revenge, but ultimately it’s about the cost of inhumanity, war, and revenge. It posits, over and over again, that there’s no finish line to war. The mission is never accomplished.

You fight and you run, and then you keep fighting, you keep running.

The only way out is to forgive.

There’s another full season after this moment with Gaius Baltar, the series’ traitor to end all traitors, but BSG essentially ends with forgiveness. But the ending everyone is cranky about is the one where the colonists, the robots, and the folks who are somewhere in between, settle on Earth. They scatter, throw away their old tools and rules, and get to work building a new community.

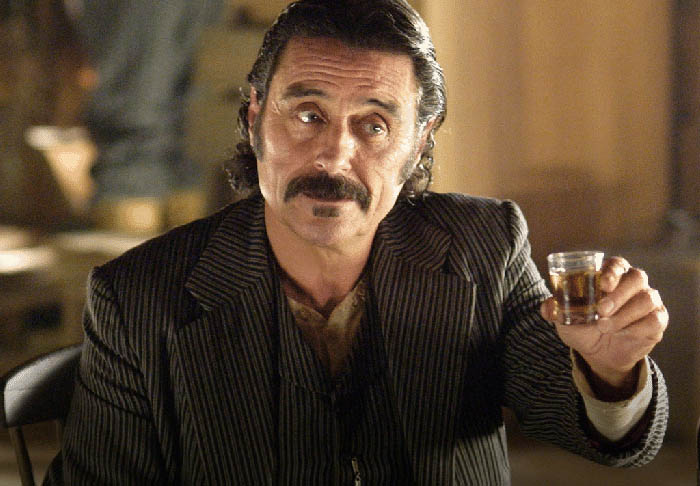

Deadwood aired on HBO from 2004 to 2006 over the course of three brief seasons. It started after BSG and finished before it, but you can see it as a spiritual sequel. Deadwood is about going further than the map allows, having brought with you everything you know you are and don’t know you are, and recreating society. The good things, the bad things, the things you tried to leave behind.

In Deadwood: Stories of the Black Hills, show creator David Milch says he originally pitched a series about cops in Ancient Rome working under the mad emperor Nero, “intstrument(s) of order, in a world that could invoke no ordering principle besides, ‘Do what an insane person tells you to.’” HBO turned that pitch down because they’d already greenlit another series set in that period. But Milch, best known for his work on Hill Street Blues and NYPD Blue, wasn’t ready to return to the modern day.

“The human heart yearns to be lifted up,” he wrote. “What lifts us up with less excess weight and baggage better than anything else is a story about our brothers and sisters. But it’s disingenuous not to recognize that certain moments in history make it hard to acknowledge all our familial connections. It was for something like that reason, in the aftermath of the events of September 11, I didn’t want to do a story with a contemporary setting.”

Like BSG, Deadwood looks like a genre show—a Western—but it functions as a parable for rebuilding after a great trauma. Deadwood’s inhabitants are survivors of a catastrophe. In this case, the catastrophe is the first century of America and the Civil War, but there are also catastrophes of the heart. The gunslinger Wild Bill Hickok has been driven from civilization for gambling debts, vagrancy, and a propensity for violence. Seth Bullock has walked away from his responsibilities as a lawman to make money, but quickly finds himself enforcing the law in a town with no laws. Alma Garret married into money, lost her husband, gained his money, and stayed to build up a new land instead of returning to the old one.

They have all fled their old lives, often their old families, and vowed to start anew. But they quickly find the best versions of themselves by establishing new familial connections. They are often family fighting against one another, but they always come back together. They forgive trespasses, they commit themselves to kindness and selflessness and what is best for the larger society.

Eulogizing Wild Bill in season one, Reverend Smith paraphrases St. Paul and Corinthians: “For the body is not one member, but many. He tells us, the eye cannot say unto the hand, I have no need of thee. Nor again the head to the feet, I have no need of thee. Nay, much more those members of the body which seem to be more feeble, and those members of the body which we think of as less honorable, all are necessary. He says that there should be no schism in the body but that the members should have the same care, one to another. And whether one member suffer, all the members suffer with it.”

We remain connected, even when we say we are separate. Even if we’ve left a larger world, we bring our inner worlds with us. When outsiders come to a new world, there is going to be natural tension and aggression and even violence. But like has happened before, they will eventually be subsumed into the order.

How does that body grow? When a community has come together, whether from the ashes of catastrophe or not, is it doomed to fall apart again? Does it rot from the inside out?

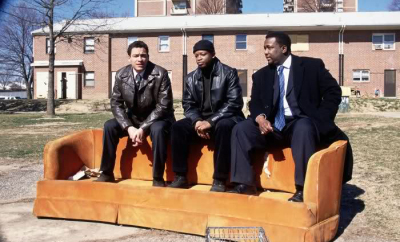

The Wire ran on HBO from 2002 to 2008, and again it looked like a genre show. It came wrapped up as a police procedural, but in reality it brings us closer to the catastrophe again. This is the community grown rotten, or maybe just so large that the hand no longer realizes it is the same organism as the eye.

The general assessment of The Wire is that it’s about American institutions and how they fail individuals. Over the course of its first season, The Wire reveals itself to be more than a cop show. It’s about rules. It’s about the changing landscape of law enforcement and the social contract.

But if it’s not overt for the first four seasons, by the time the fifth and final season arrived—airing in 2008, before the election of Barack Obama—it was clear this was a show that was pessimistic about organizations, those who lead them, and the compromises those leaders make. One of the major storylines of season five has Detectives McNulty and Freamon, formerly proud spires of doing what’s right, no matter the cost, inventing a serial killer and feeding information on said killer to the press in order to gain funding to continue actual police work, including the continuing case against Marlo Stanfield and his drug dealing operation.

Now, I can’t say with certainty that the rationale for the 2004 invasion of Iraq and the subsequent nearly 9-year Iraq War was based on information the leaders of the United States of America knew to be false. It’s true that no weapons of mass destruction were found, in spite of Colin Powell’s United Nations presentation.

The first episode of season five begins with the epitaph, The bigger the lie the more they believe. It’s easy to see this entire season as exploring the question of, is it ever okay to lie for the greater good? If so, who gets to decide what the greater good really is?

After watching five seasons of The Wire, it can be hard to remember that Baltimore is a real American city in the 21st century. Detroit has never had a comparable fictional examination, but it also continues to be a real American city in decline, perhaps on the edge of catastrophe. The Nation called Camden, New Jersey, the “City of Ruins.” David Simon, the creator and executive producer of The Wire wrote in the Guardian in 2013 that there are “two Americas,” and that capitalism “has achieved its dominance without regard to a social compact, without being connected to any other metric for human progress.”

The eye has said to the hand, I have no need of thee.