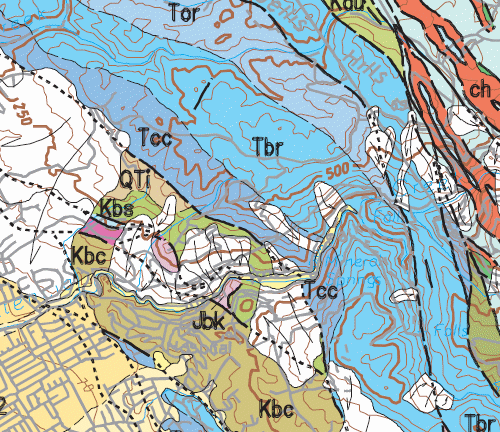

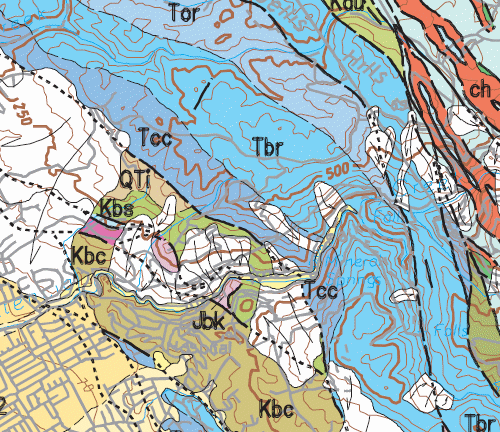

Have a look at the geologic map of the area (from USGS Open-File Map 98-795) below.

Penitencia Creek comes downhill from the right center and exits on the lower left. The park entrance is right at the edge of bedrock (Kbc, conglomerate of the Berryessa Formation), and the uppermost parking area is at the Tcc (Claremont Formation) mark. Hiking trails run along both sides of the creek giving you a good look at all the rock units from the park entrance to the Briones Formation (Tbr) on the right. Let's see some, starting with the conglomerate.

This very coarse grained rock and its related sandstone in the Berryessa Formation are part of the Great Valley Sequence, thick beds of sedimentary rock built up while the Sierra Nevada was intruding all that granite, back around 100 million years ago in Cretaceous time.

Behind the boulder is Eagle Rock, which corresponds to the pinkish blob surrounded by landslides to the right of the "Kbc" label. You can climb up there or stroll through the other outcrop labeled Jbk. The rock itself is well-traveled volcanic material that has been permeated and altered by hot mineralizing fluids. Here's a chunk of it.

The large outcrop along the creek gives the park its name. An early visitor mistook the whitish crust on these rocks as alum, which would have been a nice find at the time. It's actually sulfate minerals, but the name stuck.

Farther upstream, just past the visitor center, is where the mineral spring zone begins. On the geologic map, it corresponds to the exposure of Claremont Formation (Tcc), a belt of ribbon chert of Miocene age (about 10 million years) familiar in the East Bay Hills. Here the chert is dark with organic matter and its beds are upturned almost to vertical. That combination of chemistry and structure has given rise to warm upwellings of chemically interesting groundwater.

There are more than 20 different springs here, each with a nice stone housing. The ones I dipped my fingers into were bathtub-warm, and the water is sulfur-scented. A hundred years ago Alum Rock Park was a big health spa, with a rail line direct from downtown. That was when the stonework was done. You can see where seepage has built up cones of minerals on the lower wall. All of the springs issue from the Claremont chert—here's a closeup of the chert and the mineral crust.

After all that excitement you may want to continue upstream, into the structurally overlying and younger Briones Formation. This set of rocks is coarser grained than the Claremont, deposited nearer to shore. The other way to look at it is that the shoreline grew closer to this spot as geologic time progressed. This is a well-scrubbed outcrop in the stream bed that shows its bedding.

Parts of the Briones are so full of fossils that the rock is best described as shell hash. You'll see this same stone at Lime Ridge in Walnut Creek and other places in the East Bay.

This whole belt of rocks lies in the zone where the Hayward fault merges with the Calaveras fault. On the map above, the Calaveras runs down the right edge of the Briones Formation, between the Calaveras and Anderson Reservoirs. The Hayward fault formally ends a few miles northwest, but the many smaller faults marked as heavy lines are of the same ilk and reflect the same tectonics. Friction along the faults may account for the warmth of the springs, just one more way that the deep Earth affects us in our region.

You can also check out QUEST's Alum Rock Science Hike for more info.

37.397 -121.798

Mineral springs, fresh air, and a cross-section of South Bay history—not to mention its rocks—are all on display at Alum Rock Park. All photos by Andrew Alden.

Mineral springs, fresh air, and a cross-section of South Bay history—not to mention its rocks—are all on display at Alum Rock Park. All photos by Andrew Alden.