On Monday the 13th, California's largest earthquake in two years, a magnitude 5.6 event, occurred way up in the state's northwest. That's the real "earthquake country" in our state. California has had eight earthquakes of magnitude 5.6 or larger in the last 10 years, and half of them were up there. I think of the area as our Alaska—cold, remote, wet, foggy and rocky. Geologists call it part of Cascadia. What's that?

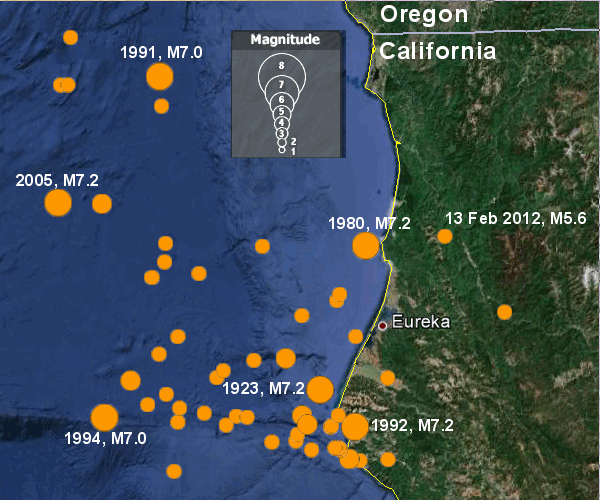

Cascadia refers to the country overlying the Cascadia subduction zone, where a small tectonic plate, the Juan de Fuca plate, is working its way beneath the west coast of North America. From north to south it extends from Canada's Vancouver Island all the way through Washington and Oregon and into California, ending at Cape Mendocino. From west to east it follows the Juan de Fuca plate from the offshore fault where it first plunges beneath the seafloor to approximately the long volcanic chain of the High Cascades. I've marked it on this earthquake map along with the February 13 earthquake.

Only a little of Cascadia extends into California, but this whole subduction zone could rupture at once in a colossal earthquake the size of Japan's in March 2011 or Sumatra's in December 2004; that is, a giant magnitude 9 event. Such a Cascadia subduction quake happened last in January 1700. We aren't sure whether the rupture came as far south as California then, but the next one certainly could.

None of California's other faults are capable of earthquakes that size . . . not even one-tenth that size. Not even the San Andreas fault. An earthquake's energy comes from the amount of rock that can take up stress, and the San Andreas is a vertical ribbon little more than 20 kilometers wide from the ground down. Like a strand of fettucine, it doesn't add up to much no matter how long it gets. Magnitude 8 is considered an absolute maximum for most of California, a very large quake but still only about 3 percent of a magnitude 9 in total energy. In Cascadia, however, the subduction-zone fault is a slanted ribbon with much more surface area—a lasagna noodle. The tectonic geometry is the same as in Japan and Sumatra. Chile, where magnitude 9 events have also occurred, is the same. So is Alaska, where a 9.2 quake occurred in 1964. That's another reason I think of this part of California as our Alaska.

Northwestern California releases more seismic energy than any other part of the state. The map below shows about 60 earthquakes of magnitude 5 and greater in the last 40 years. Six of these reached magnitude 7.

You may notice that most of the events occurred offshore, beyond the subduction zone (which runs just west of the box with the magnitude key). These arise from cracking within the Juan de Fuca plate as it approaches the coast. There's very little activity inland, along the subduction zone itself. That part of the fault is considered to be locked, building up strain and growing closer to failure.