Misplace your car keys? Forget to buy milk at the store? Temporary lapses in memory can be such a nuisance. But for those coping with a memory-impairing disease or traumatic brain injury, this kind of memory loss can become debilitating.

“Anyone who has witnessed the effects of memory loss in another person knows its toll and how few options are available to treat it,” says Justin Sanchez, program manager at the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, better known as DARPA.

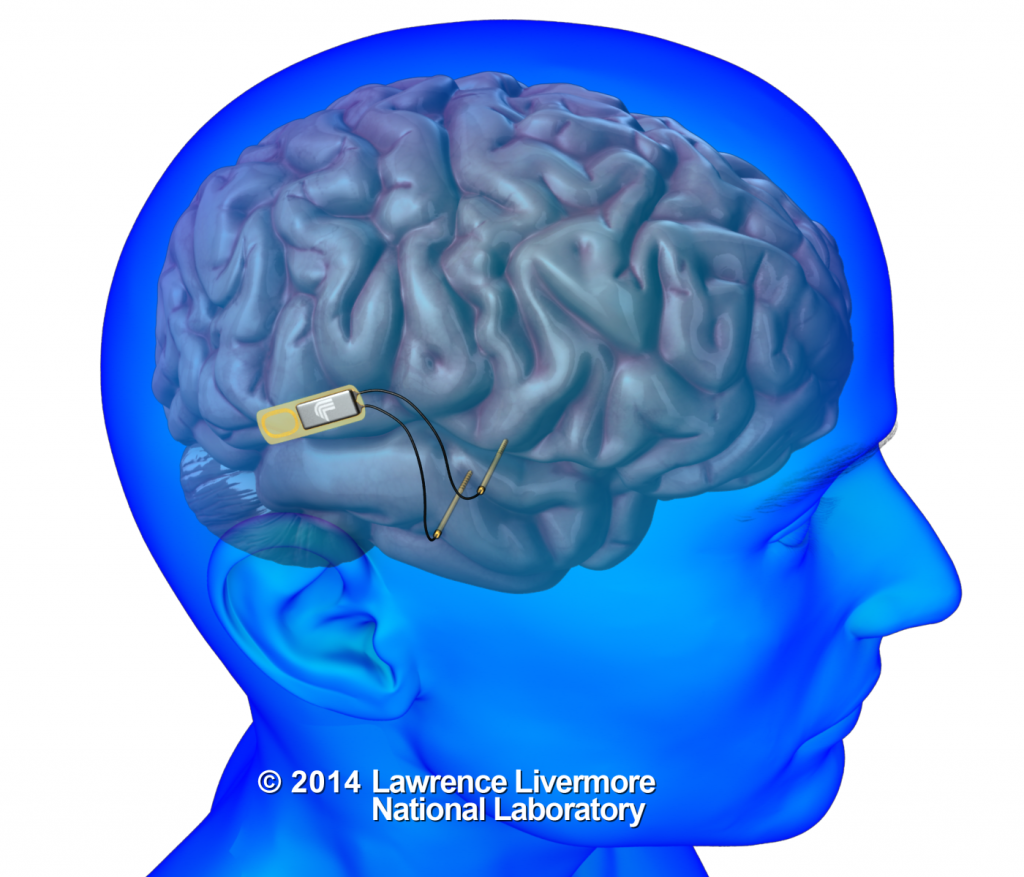

On Tuesday DARPA announced a new multi-million dollar effort to develop and test a new generation of therapeutic brain implants that will help service members, veterans and civilians recover from memory loss caused by brain trauma or disease.

Here’s the tricky thing about treating memory loss: Scientists still don’t completely understand how the brain goes about capturing, storing and retrieving memories. Sure, they know that regions such as the hippocampus are important for the process. But developing precise medical interventions will require a much deeper understanding of how memory works.

How deep? Try single neuron deep.