How Ticks Dig In With a Mouth Full of Hooks

Spring is here. Unfortunately for hikers and picnickers out enjoying the warmer weather, the new season is prime time for ticks, which can transmit bacteria that cause Lyme disease.

How they latch on — and stay on — is a feat of engineering that scientists have been piecing together. Once you know how a tick’s mouth works, you understand why it’s impossible to simply flick a tick.

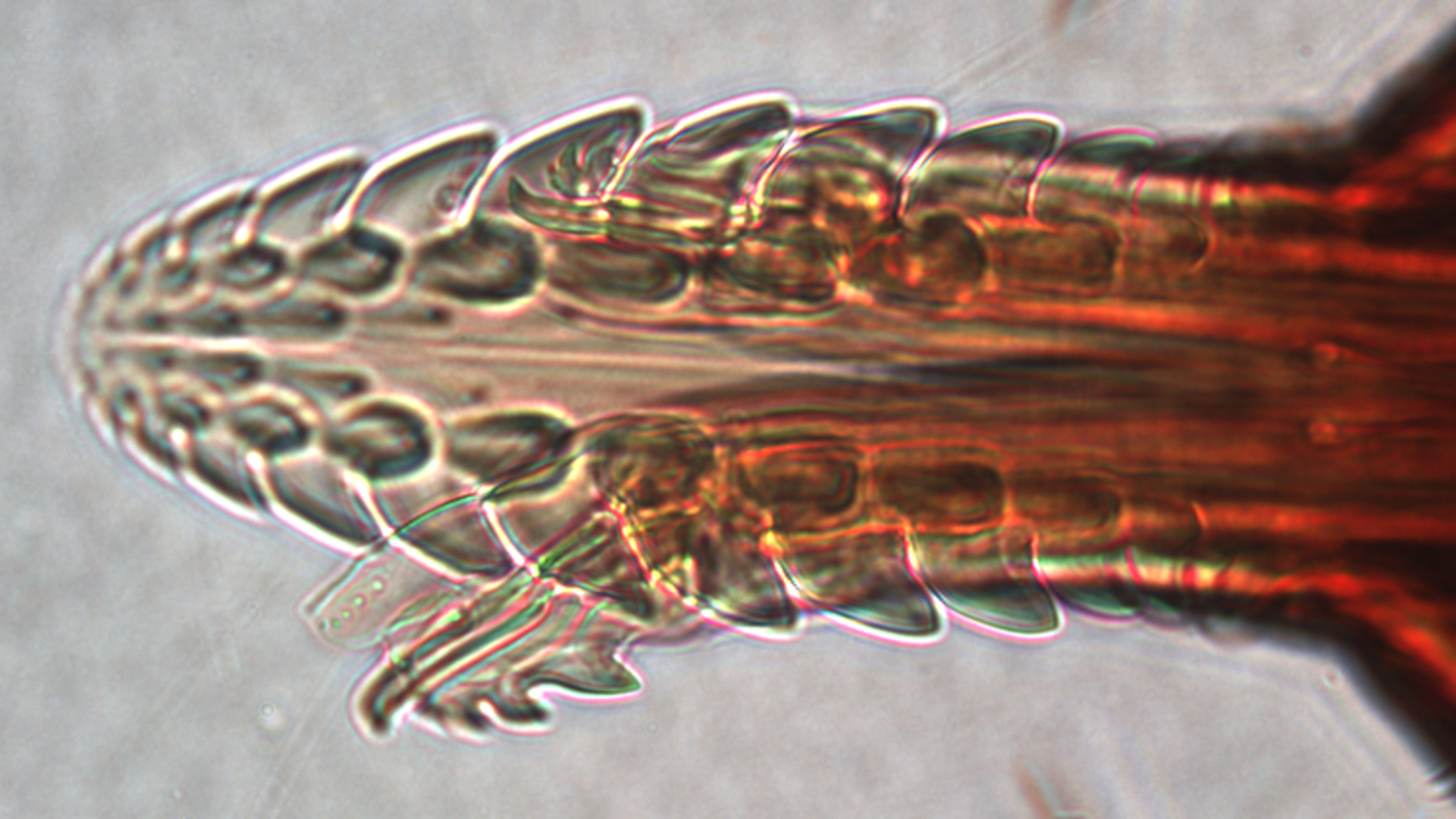

The key to their success is a menacing mouth covered in hooks that they use to get under the surface of our skin and attach themselves for several days while they fatten up on our blood.

“Ticks have a lovely, evolved mouth part for doing exactly what they need to do, which is extended feeding,” said Kerry Padgett, supervising public health biologist at the California Department of Public Health in Richmond. “They’re not like a mosquito that can just put their mouth parts in and out nicely, like a hypodermic needle.”

Instead, a tick digs in using two sets of hooks. Each set looks like a hand with three hooked fingers. The hooks dig in and wriggle into the skin. Then these “hands” bend in unison to perform approximately half-a-dozen breaststrokes that pull skin out of the way so the tick can push in a long stubby part called the hypostome.

“It’s almost like swimming into the skin,” said Dania Richter, a biologist at the Technische Universität Braunschweig in Germany, who has studied the mechanism closely. “By bending the hooks it’s engaging the skin. It’s pulling the skin when it retracts.”

The bottom of their long hypostome is also covered in rows of hooks that give it the look of a chainsaw. Those hooks act like mini-harpoons, anchoring the tick to us for the long haul.

“They’re teeth that are backwards facing, similar to one of those gates you would drive over, but you’re not allowed to back up or else you’d puncture your tires,” said Padgett.

Compounds in ticks’ saliva help blood pool under the surface of our skin. Ticks sip it, like drinking from a straw.

Ticks need to stay firmly attached because they’re going in for a meal that can last for three to 10 days, depending on whether they’re young ticks or adult females. Compare that to a speedy mosquito, which digs in to human skin, sucks blood and leaves, all within seconds.

For ticks, the stakes are high because instead of taking small meals they need to gorge themselves each time. A western blacklegged tick, the species that transmits Lyme bacteria to humans along the Pacific Coast, lives three years. But in that time it eats only three huge meals, each one necessary for it to grow to its next life stage. It needs enough blood to grow from larva to nymph, nymph to adult, and then for females to lay their eggs.

An adult female tick drinks so much blood during its one meal that its weight increases 200 times, said Richter.

So what’s the best way to get rid of a tick?

The hooks that make these infrequent, but long, banquets possible are what make it hard to pull out a tick. But pulling one out isn’t as hard as you may think. Padgett recommends grabbing the tick close to the skin using a pair of fine tweezers and simply pulling straight up.

“No twisting or jerking,” she said. “Use a smooth motion pulling up.”

Padgett warned against using other strategies.

“Don’t use Vaseline or try to burn the tick or use a cotton swab soaked in soft soap or any of these other techniques that might take a little longer or might not work at all,” she said. “You really want to remove the tick as soon as possible.”

Time is of the essence. If an infected tick bites humans, it actually takes at least 24 hours before Lyme bacteria start swimming out in the saliva the tick drips into its host.

So don’t worry if the tick’s mouth parts — the ones covered in those tenacious hooks — stay behind when you pull.

“The mouth parts are not going to transmit disease to people,” said Padgett.

Once the tick’s body is no longer attached, it can’t transmit bacteria. And if the mouth stays behind in your skin, it will eventually work its way out, sort of like a splinter does, she said.

About 100 cases of Lyme disease are diagnosed each year in California, where infections occur mainly in Northern California. Ticks need humid environments and don’t do well in the desert.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates that more than 300,000 cases of Lyme disease occur each year in the United States, mainly in the Northeast and upper Midwest. Initial symptoms may include headaches, fatigue, and muscle and joint pain, as well as a rash at the site of the bite that develops up to a month later. If the infection isn’t treated with antibiotics, it can lead to problems such as nerve pain.

The spring brings a particular threat to Northern California, where small immature ticks called nymphs become more abundant. Nymphs can be found year-round in Northern California, but their activity peaks in late spring through early summer, according to the California Department of Public Health.

Nymphs are hard to find because they’re about the size of a poppyseed and less colorful than the red female adult western blacklegged ticks that are active in Northern California’s forests in the winter. Nymphs are light brown, with dark innards visible through their translucent bodies.

“Most people are infected by nymphal ticks because they’re small and you tend not to catch them,” said Tara Roth, an ecologist with the San Mateo County Mosquito and Vector Control District.

Nymphs are also more of a threat than adult ticks because they’re more likely to carry Lyme bacteria, said Padgett.

Adult ticks carry Lyme bacteria less often than nymphs because of a biological quirk in California. Ticks that carry Lyme bacteria and feed on the western fence lizard lose their infection in the process. The lizard’s blood actually clears the infection, said Andrea Swei, who studies ticks and disease transmission at San Francisco State University.

Ticks most commonly feed on the lizards when they’re larvae and nymphs. If a nymph had been infected before it fed on a lizard, it will no longer be infected after it grows into an adult.

Studies in Northern California indicate that western blacklegged nymphs are most commonly found in leaf litter, and on wood products such as downed logs, tree trunks and even wooden picnic tables, according to the state public health department.

“We also find them on mossy rocks,” said Padgett.

Experts say a key way to avoid tick bites is to be prepared. Wear long pants and put on repellent next time you’re planning a hike or picnic in an area where ticks and their impressive hooks may be lurking.