Samurai Wasps Say 'Smell Ya Later, Stink Bugs'

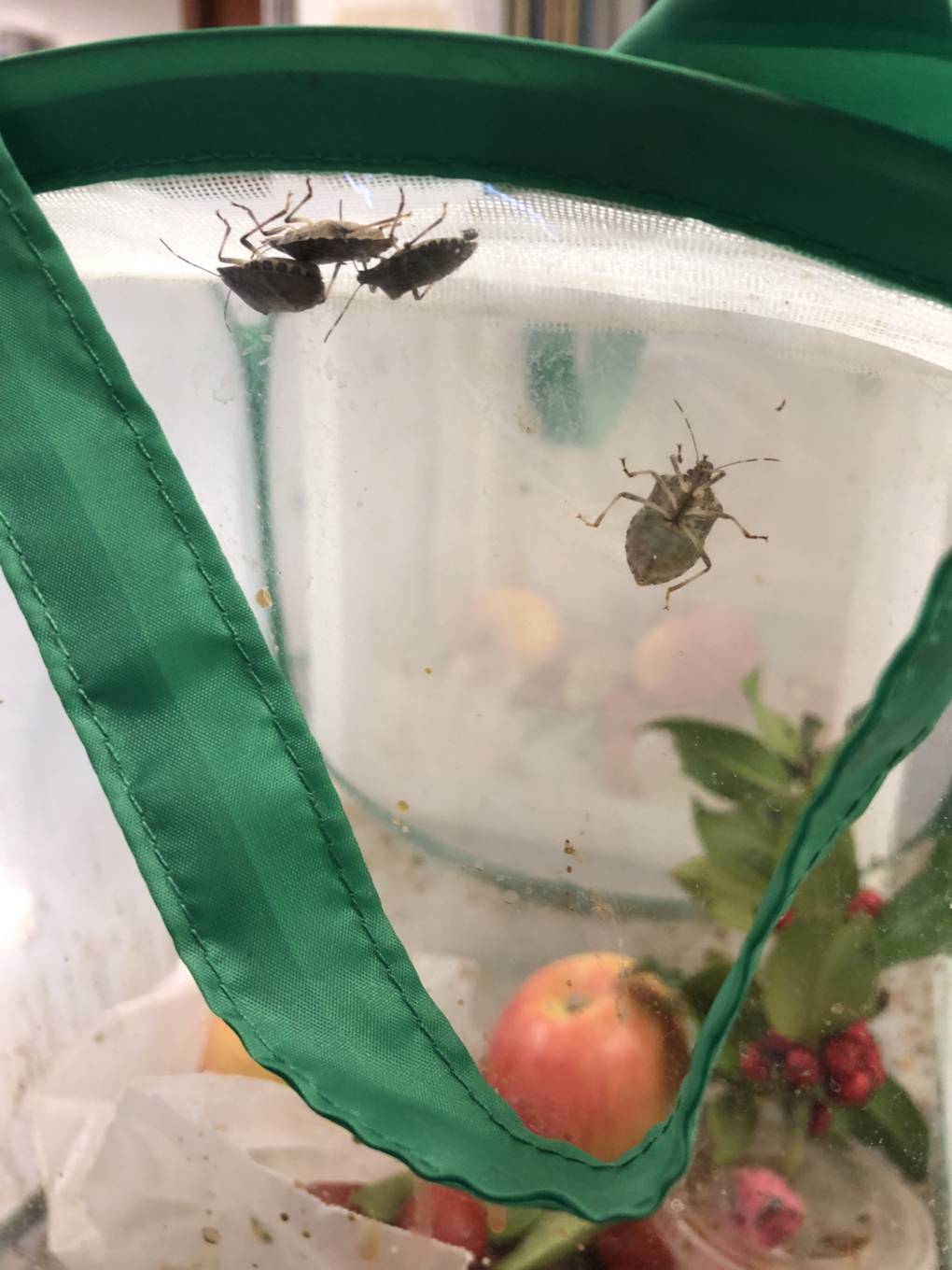

It looks rather harmless at first glance. With a speckled exterior and a shieldlike shape, the brown marmorated stink bug doesn’t appear to be different from any other six-legged insect that might pop up in your garden. But this particular bug, which arrived in the U.S. from Asia in the mid-1990s and smells like old socks when it is squashed, is a real nuisance. Not only can it invade homes by the thousands in the wintertime, it’s one formidable agricultural pest, eating millions of dollars of peaches, apples and other crops since 2010.

Scientists are now investigating a new tactic in the war on the stink bugs: the possibility of relying on one of the bug’s natural enemies, the samurai wasp.

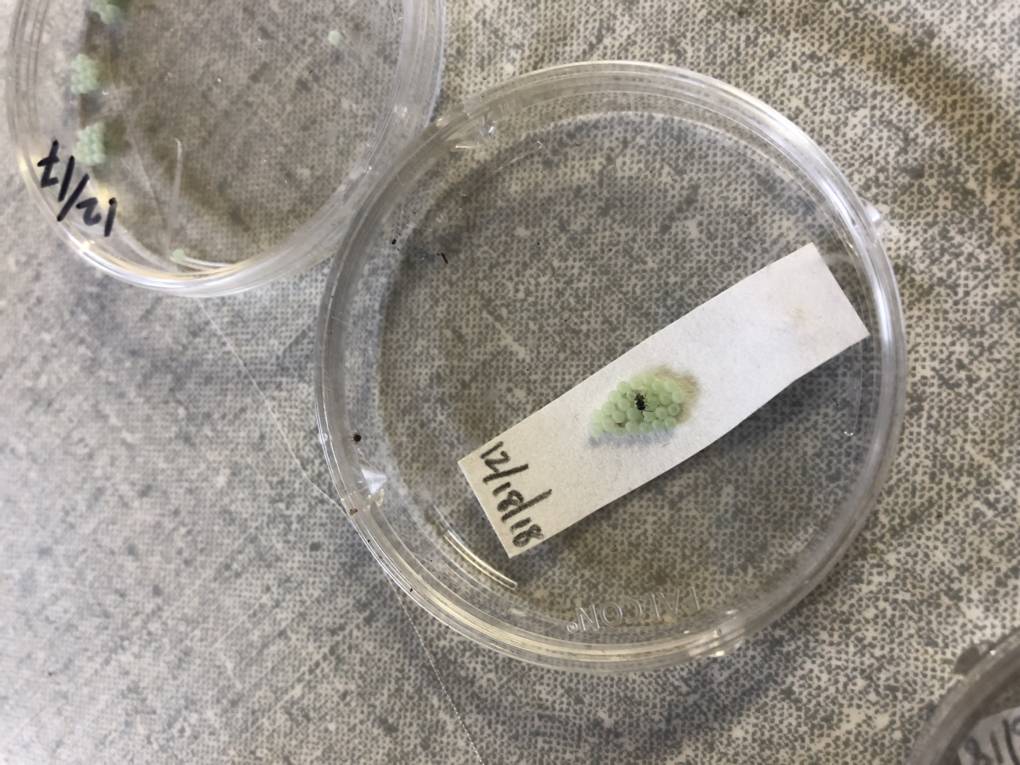

Also native to Asia, this parasitic wasp keeps the stink bug population in check there. How? By colonizing its rivals’ eggs.

A female wasp will lay its own egg inside of a stink bug’s egg. About two weeks later, an adult samurai wasp will emerge. Between 60 to 90 percent of stink bug eggs in Asia are destroyed this way.

But introducing a non-native biological control can pose risks, as previous scientists have discovered when trying to manage invasive species. In the late 1800s, mongooses released in Hawaii to manage rat populations wiped out native birds and turtles instead. In 1935, cane toads deployed in Australia not only failed to reduce the beetles that were infesting sugar cane plantations, but they also created a host of other problems — including inadvertently killing animals that fed on the poisonous amphibians.

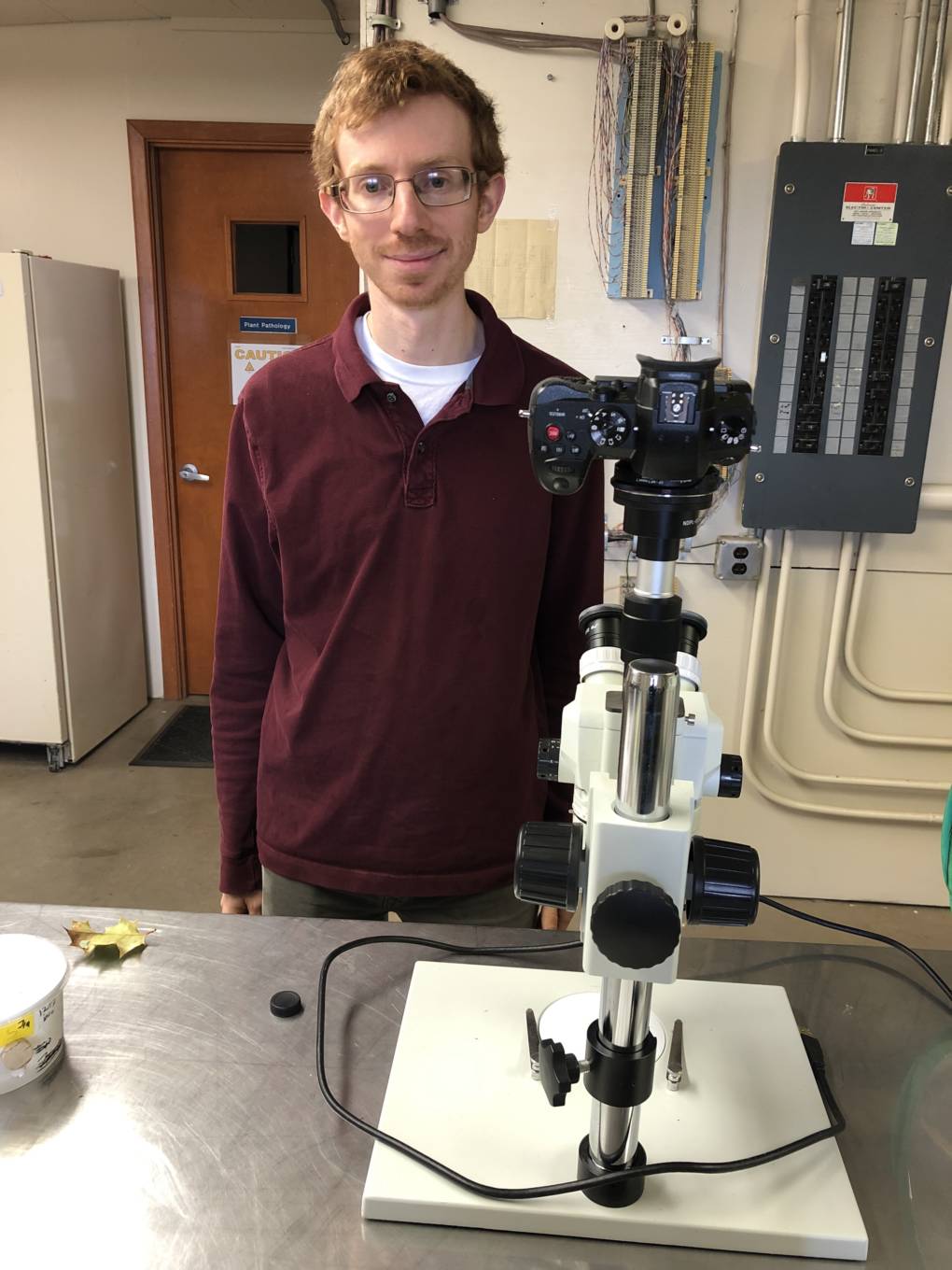

Scientists who were considering bringing samurai wasps into the U.S. discovered they’d already hitchhiked here on their own. The wasps have settled down in Oregon, where stink bugs have been feasting on hazelnuts and berries. David Lowenstein, a postdoctoral research associate at Oregon State University, has been rearing both stink bug and samurai wasp colonies.

“We hope that the wasp, which controls the stink bug well in its native range of China and South Korea, will do the same in the USA,” he said.

Lowenstein said he has spent the last two years distributing the wasp around parts of Oregon where stink bugs are a threat to agriculture.

“I’ve had some success getting the wasps to survive the winter and be detected a year later,” he said.

What’s the biggest challenge with using the samurai wasps on a wider scale? Rearing and releasing thousands of them at multiple locations.

“To get a high number of samurai wasps, I need to also obtain enough stink bug eggs,” Lowenstein said.

He and his team will release more wasps this summer, and he’s hoping they’ll find a partner to help them rear and release much larger numbers within two to three years.

It could take much longer before the samurai wasp can be used for pest control around the country, as it has been found in only 12 states and Washington, D.C. But research is moving forward in other states, including New Jersey and California. While commercial crops grown in California haven’t felt the effects yet of the stink bug, researchers at UC Riverside are still studying them — and samurai wasps — in the event that they pose a serious risk to the state’s multibillion-dollar agricultural industry. While there’s no sign of the wasps in California yet, chances are they’ll be following their foe from other states, too.