How Lice Turn Your Hair Into Their Jungle Gym

At the end of spring break, your kids might be bringing back something more than just good memories of that family vacation. Holidays, it turns out, are a time when head lice spread.

Anytime kids’ noggins are in direct contact — when they’re sitting or sleeping next to each other — or when parents and children spend time cuddling, lice have a chance to crawl from one head to another.

After holidays or popular kids’ movies, Melissa Shilliday sees an uptick in business at her NitPixies hair salons, located in Oakland and San Rafael. At the salons, for $115 per person, a technician will comb lice out with a special metal comb that extracts the tiny insects between its closely spaced teeth.

“It’s always slow a couple of weeks before a Pixar movie comes out,” said Shilliday.

Head lice can move only by crawling on hair. They glue their eggs to individual strands, nice and close to the scalp, where the heat helps them hatch. They feed on blood several times a day. And even though head lice can spread by laying their eggs in sports helmets and baseball caps, the main way they get around is by simply crawling from one head to another using scythe-shaped claws.

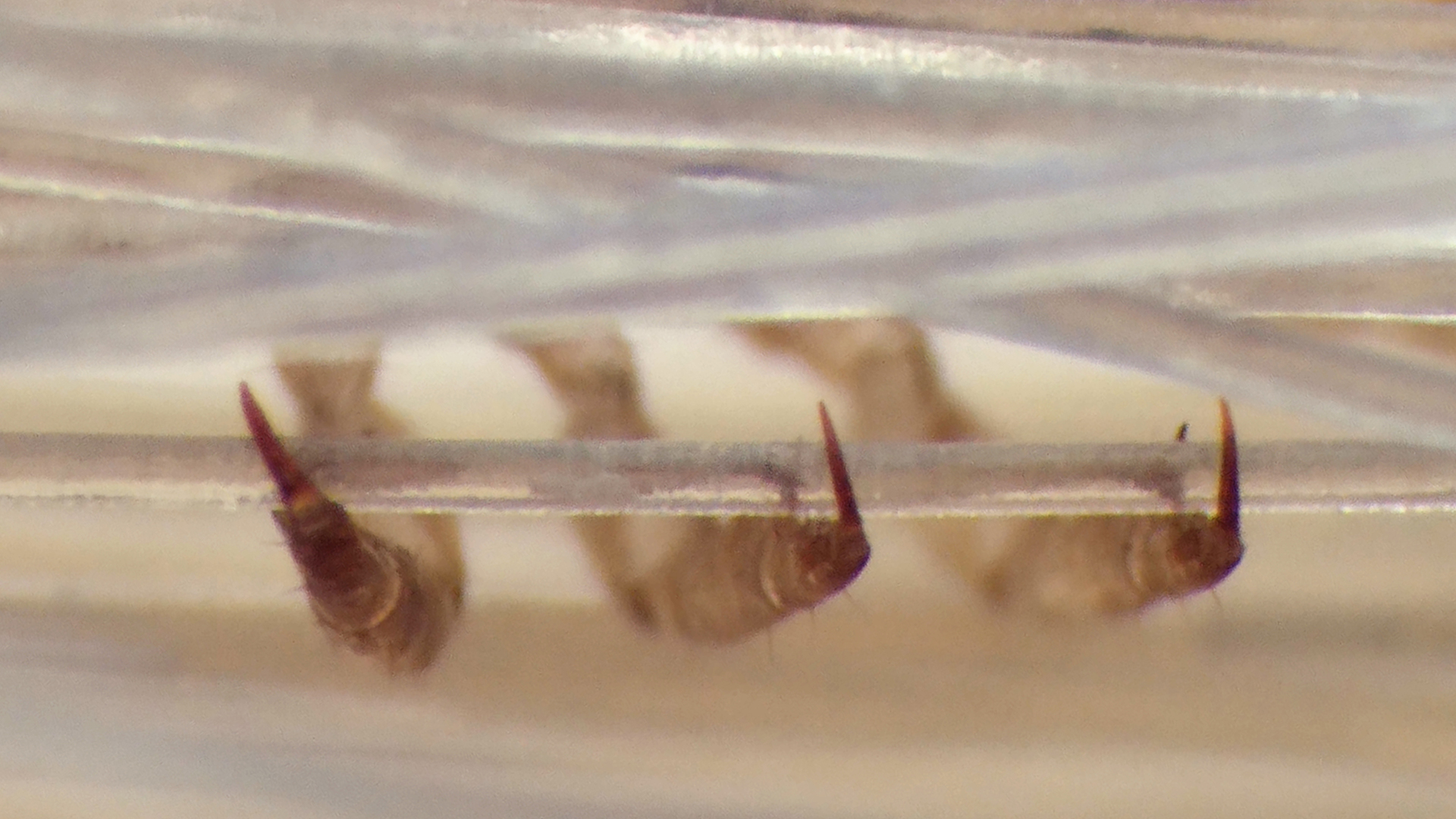

These claws, which are big relative to a louse’s body, work in unison with a small and spiky thumblike part called a spine. With the claw and spine at the end of each of its six legs, a louse grasps a hair strand to hold on tightly, or quickly crawl from hair to hair like a speedy acrobat.

Their drive to stay on a human head is strong because after they’re off and lose access to their blood meals, they starve and die within 15 to 24 hours.

Lice that live on primates and birds are all very different-looking, adapted to their unique circumstances surviving in their host’s hair or feathers. For example, lice that live in pigeon feathers are long and thin, the better to hide in the feathers’ barbs, where the birds can’t preen them out. On humans and other primates, lice claws have evolved to fit around a strand of hair.

“The curvature of it is probably pretty close to the average hair diameter that they would come in contact with for a given species of host,” said biologist David Reed, who has studied lice and evolution at the Florida Museum of Natural History.

The good news is that human head lice can’t really move to other parts of our body or onto our pets. They’re confined to the head.

“The claw and spine are adapted to hold a human hair on the scalp,” said medical entomologist Kosta Mumcuoglu, who studies lice at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. “The other hairs of the body are usually too thick for them, and they can’t hold them.”

Two other types of lice can live on the human body: the clothing louse, which lives in the clothes of people who can’t change them often enough, and the pubic louse, which spreads during sexual contact.

“(The pubic louse) has stronger claws,” said Mumcuoglu, “to catch the thicker hairs of the region.”

At NitPixies on a recent morning a mother brought her kindergartner in for treatment. She didn’t want her daughter’s name used, for fear of bullying. She had applied a common insecticide shampoo to the girl’s hair, but the lice were still there and now she wanted a professional at the San Rafael salon to comb them out.

Salon manager Losa Aupiu divided the girl’s hair into sections and combed each piece four times with a metal comb, up and down from the root out, to remove lice and eggs. Then she applied a mixture of plant oils that Aupiu said would kill any remaining lice. She sent the mother home with a metal comb and recommended she run it through her daughter’s hair for at least five days to get rid of any remaining eggs. It takes eggs six to nine days to hatch.

Combing lice out is a laborious, old-fashioned process that has become the last resort for many parents, as lice have become resistant to over-the-counter insecticide shampoos.

Between 2013 and 2015, John Clark and colleagues at the University of Massachusetts Amherst tested lice in every state except West Virginia and Alaska, and found that they had become overwhelmingly resistant to natural insecticides called pyrethrins and their synthetic version, known as pyrethroids, which are used in the most common over-the-counter lice treatments.

Other products do still work against lice, though. Prescription treatments that contain the insecticides ivermectin and spinosad are effective, said Clark. They’re prescribed to kill both lice and their eggs. Clark said treatments such as suffocants, which block the lice’s breathing holes, and hot-air devices that dry them up, also work. He added that tea tree oil works both as a repellent and a “pretty good” insecticide. And then there’s combing, which can also get good results, but is demanding.

“It takes time and effort,” he said. “You sort of have to know what you’re doing. And so most people that comb eventually get tired of it and they want something a little bit more simplistic.”