Watch Bed Bugs Get Stopped in Their Tracks

Summer is a time of travel and fun. But with every bed an exhausted traveler lies on after a day of sightseeing, the chances of bringing home an unwanted bug increase.

Bed bugs don’t fly or jump or come in from your garden. They crawl very quickly and are great at hiding in travelers’ luggage and hitching rides into their homes — or into hotel rooms.

“It would probably be a prudent thing to do a quick bed check if you’re sleeping in a strange bed,” said Michael Potter, an entomologist at the University of Kentucky who researches bed bugs. His recommendation goes for hotel rooms, as well as dorms and summer camp bunk beds.

So what does Potter do when he travels? First, he keeps his suitcase zipped up and on a credenza or metal luggage rack. Bed bugs have a hard time climbing up smooth surfaces like metal.

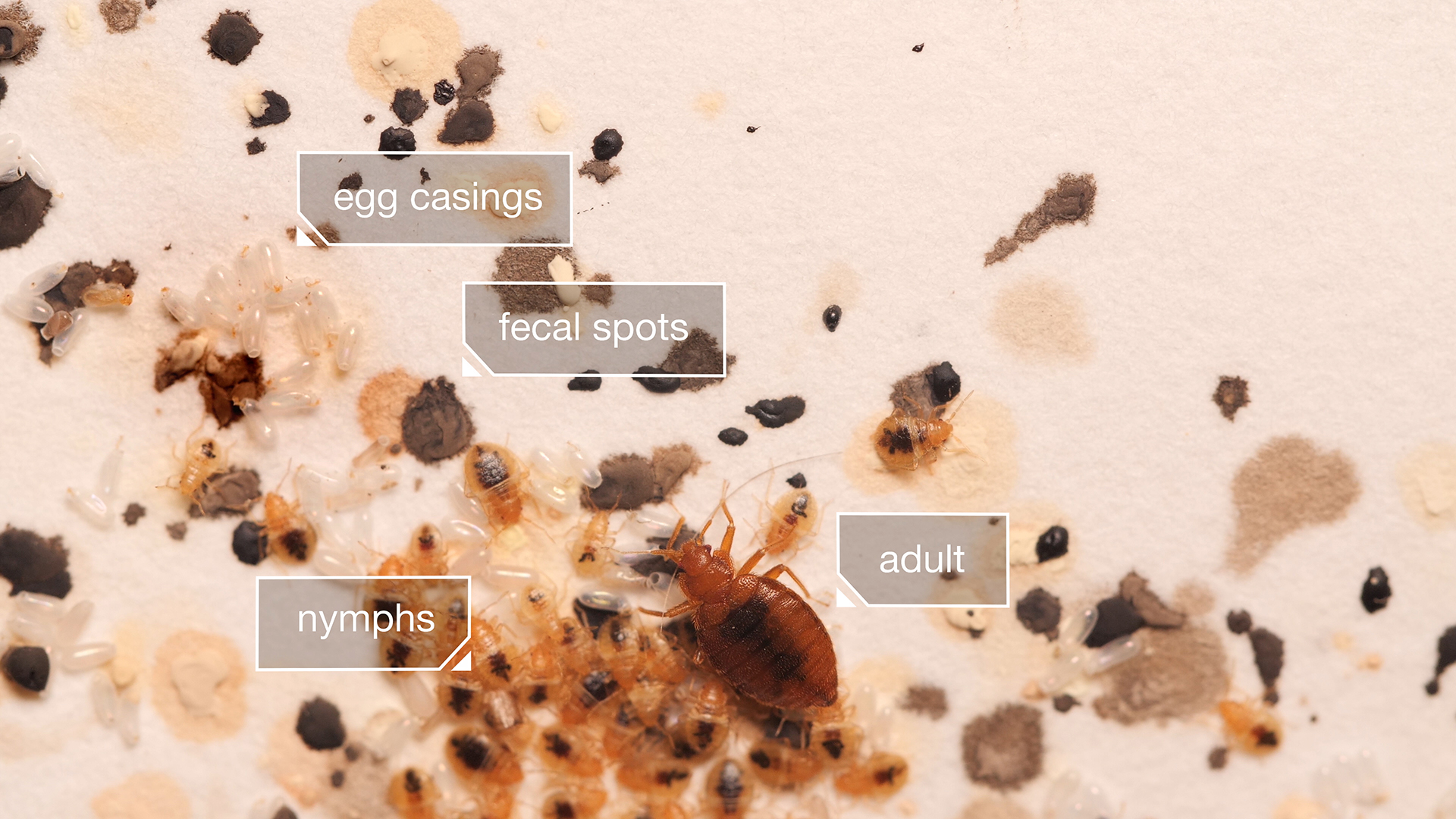

Next, he recommends pulling back the sheet at the head of the bed and checking the seams on the top and bottom of the mattress and the box spring. Contrary to popular belief, bed bugs don’t burrow into mattresses; they stay on the surface. And after feeding on us they find a hideout, where they leave telltale brown or yellow droplets of digested blood called fecal spots. If they have already had a chance to reproduce, their nest might include translucent egg casings and young yellowish nymphs.

“They’re more of a nest type of insect,” said Bill Donahue, an entomologist and owner of Sierra Research Laboratories in Modesto, where he evaluates treatments against bed bugs and other pests. “There are areas where the bed bugs will congregate.”

Adult bed bugs are about the size and color of an apple seed. Young bugs, called nymphs, are smaller and yellowish or white. Guided by the carbon dioxide and heat that sleeping humans emit, they crawl quickly up wooden bed posts and over sheets to stick their long mouth part in and drink for about five minutes, until they’re completely full. They then hide in a nearby cranny, like the seam of the mattress or behind a baseboard.

“Heaven forbid you wake up with itchy red welts during your stay,” Potter said. “Then you want to be incredibly vigilant when you get home.”

He suggests putting clothes in the dryer or leaving unzipped suitcases inside a hot car, since bed bugs are susceptible to high temperatures. Some people take days, even weeks, to react to a bed bug bite, so bites aren’t a great indicator of when you were exposed to them. And though some people can suffer a severe skin reaction, bed bugs aren’t known to transmit any diseases.

Until the 1940s, bed bugs were a common occurrence in the U.S. After being nearly eradicated by the spraying of DDT in the 1950s, they’ve made a comeback worldwide in the past 20 years, aided by the widespread movement of people. They’ve been found all around the country in settings as varied as schools, dorms, hospitals, theaters, moving vans and even funeral homes, according to Potter. And they also move around on secondhand furniture.

Apartment dwellers are more vulnerable to infestation, as bugs can crawl from one flat to another. Because bed bugs hide away, they’re difficult to treat without the help of a professional, which can be expensive.

“If you think you have bed bugs, let your landlord know right away,” said entomologist Andrew Sutherland, the University of California’s urban pest management adviser for the San Francisco Bay Area. “It’s their responsibility to do inspections and to hire a reputable pest control operator to take care of the problem.”

Because bed bugs are vulnerable to heat, a thermal treatment is “the gold standard,” said Luis Agurto, CEO of Pestec, a pest control company in the San Francisco Bay Area. Pestec places big heaters throughout an infested residence and warms it up to 122 degrees for two hours. Technicians armed with “guns” blow hot air into areas where bed bugs might be hiding.

“We’re basically making a big convection oven,” said Agurto.

After a thermal treatment, Pestec monitors for bed bugs for several weeks by placing a hard plastic cup under each bed post. The insects have no trouble climbing up the rough outside of these so-called interceptor cups, but then get trapped by the smooth inside, which they’re unable to scale. The company also uses insecticides and vacuum cleaners to get rid of infestations.

Pestec has been called in to investigate and treat infestations, from as small as six bed bugs in an apartment in San Francisco’s Haight neighborhood, to a townhouse in a housing complex in the city’s Potrero Hill district, where bugs were “on all the surfaces,” said Agurto.

Scientists are working to come up with more tools to get rid of bed bugs. At UC Irvine, biologist and engineer Catherine Loudon is collaborating with several engineering labs on campus to create synthetic surfaces that could trap bed bugs. She was inspired by the tiny hooked hairs that grow from the leaves of some varieties of beans, such as kidney and green beans. In nature, the hairs pierce through the feet of the aphids and leafhoppers that like to feed on them.

Loudon got the idea from Potter, of the University of Kentucky, who mentioned to her a folk remedy he had read about. Residents of the Balkan countries used to spread bean leaves around their beds, and in the morning they’d find bed bugs attached to them. It turns out that the bed bugs’ feet were getting impaled by the hooked hairs on the bean leaves, called trichomes. Researchers have found that trichomes are just as effective against bed bugs, even though they don’t feed on leaves.

Loudon’s goal is to mimic a bean leaf’s mechanism to create an inexpensive, portable trap.

“You could imagine a strip that would act as a barrier that could be placed virtually anywhere: across the portal to a room, behind the headboard, on subway seats, an airplane,” Loudon said. “They have six legs, so that’s six opportunities to get trapped.”

Laura Shields contributed reporting.