A sunny walk along San Francisco’s Embarcadero is about as nice as it gets, with the waterside promenade framed by a stunning view of the Bay Bridge. Strolling day trippers can also visit much-loved city attractions such as the Exploratorium science museum and the Ferry Building, loaded with gourmet snacks.

King Tides: A Story of the Moon, Sun and Sea

This weekend, however, all that charm is going to be flanked by a sobering reminder of climate change. The Embarcadero is also one of the premier spots in the region to glimpse the future as it relates to rising seas.

“The King Tides of today are the standard high tides of tomorrow,” said Lori Lambertson, an educator at the Exploratorium who will lead a Saturday morning walk between Piers 3 and 5, so that members of the public can see, photograph and learn about the phenomenon.

King tides receive their royal designation because they produce the highest, as well as the lowest, tides of the year. In the winter, they rise and fall along the Pacific coast when the sun and moon line up in their coziest proximity to Earth, exerting their greatest gravitational pull upon ocean waters.

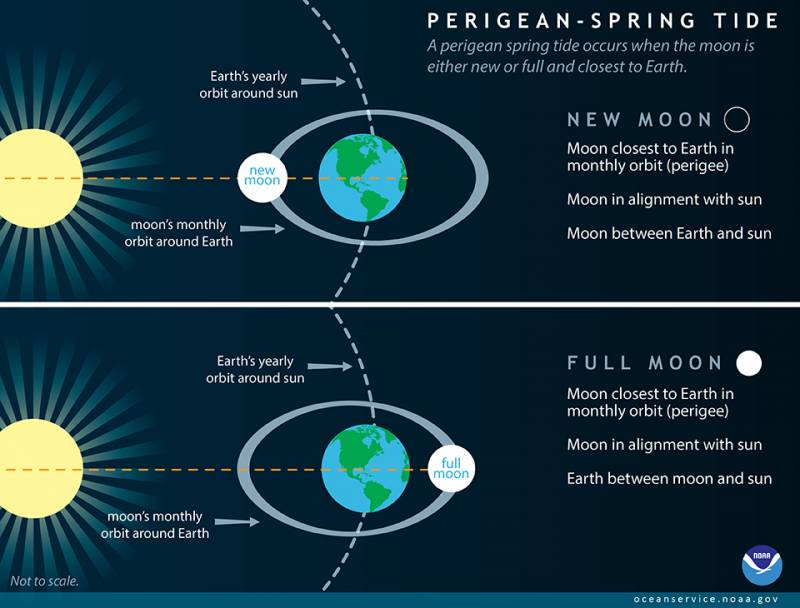

Of course, tides fluctuate constantly. There are the bimonthly “spring tides,” which have nothing to do with the season; the name refers to water “springing forth” during the full and new moons, when tidal swings are greater than normal. The first spring tide occurs when the moon is “new” and invisible to earthlings, and it hangs directly between our planet and the sun, with both bodies gravitationally pulling on our waters. Then, during the full moon phase, it’s Earth that’s in the middle; the ocean’s waters are still pulled higher by gravity, but in different directions.

Three or four times a year, one of these spring tides coincides with perigee of the moon, when it has reached its closest point to the Earth in a 28-day orbit. This creates a “perigean spring tide,” with the difference from a normal spring tide generally measured in inches.

Basically, all king tides are perigean spring tides, but all perigean spring tides are not necessarily king tides. (Do not let this distress you; just embrace the wonder and complexity of gravity and the ocean.) Along the Pacific coast, the winter perigean spring tides are more noticeable and more likely to contribute to flooding than summer tides, owing to winter weather patterns.

While high and low tides are a product of scientific phenomena, the terminology we use to describe them is not. (The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration simply says, “A King Tide is a non-scientific term people often use to describe exceptionally high tides.”) So what qualifies as a king tide depends on whom you ask. Thus, the frequency of king tides is described differently by different sources — anywhere between 1-4 times a year.

Bay Area residents will be able to witness the first king tides of the year throughout this weekend, with a second set occuring Feb. 8-10.

A Glimpse of the Future

The inspiration for the creation of the California King Tides Project was a perception that the public conversation around climate change was unhelpful and even counterproductive, says Marina Psaros, the project’s co-founder.

“It was about drowning polar bears and things that were happening far away,” said Psaros, who currently works for the San Francisco Public Utilities Commission on clean energy. She thought many of the people talking about climate change seemed fixated on difficult and technical scientific questions that were incomprehensible to all but the experts.

“So we asked, ‘Is there any way to put people at the center of their own experience with this, instead of beating them over the head with science or with polar bears?'”

The project emphasizes king tides as a local preview of what’s in store as related to rising seas caused by climate change. As the Earth warms, water expands and occupies more space. Melting ice runs into the ocean and increases its volume. These two consequences of a warmer climate are so far estimated to have contributed equally to sea level rise, according to Lambertson. The temporary — for now — surge in sea level during king tides gives us a chance to observe the areas first on the list to be impacted.

“You don’t have to know all the science,” says Psaros. “You can just go out and see what’s at risk in your community, go out during a king tide and watch the water spill over the Embarcadero.”

Trying to Adapt

More sea level rise is certain, though exactly how fast it’s coming is unclear. The water may creep up slowly, or it may rise rapidly.

The San Francisco Bay has already gone up about 8 inches — a measurement taken at the Golden Gate Bridge — in the last 100 years, giving officials in low-lying areas an impetus to prepare for the coming encroachment of the sea.

The Marin County Flood Control District, for example, is looking at how to move levees back to give waterways like the lower Novato Creek a wider floodplain and more room to flow and transport sediment. The district is also interested in building up new tidal marshes, which will act like sponges and slow the rise and fall of water levels.

In 2018, voters in Foster City overwhelmingly approved a tax on themselves to pay for raising a levee. To protect the Embarcadero, San Francisco voters passed by more than 4 to 1 a bond measure to strengthen the crumbing sea wall.

In terms of just how much higher the water is going to get, recent indications from climate studies have not been good.

“Every time the IPCC [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] has issued a new report, the higher boundary of where seas might rise … get(s) higher and higher,” said Psaros.

Amid these worries, she sees people who want to be able to do something.

“And something they can do is actually help scientists and policymakers, by going out and getting the data that we need in order to make better decisions.”

Psaros says her favorite kind of data for participants to collect is sociological. She remembers in particular working with a continuation high school where the students wanted to do more than just collect pictures of the tides. She created a survey for them with questions about climate change so they could gather responses from the public.

“These kids were from everywhere and they were given this assignment to go talk to people in their community. So the results they brought back were … Tagalog and Vietnamese and Spanish and a bunch of languages and perspectives that governments want but often just can’t get,” Psaros said. “Newcomer communities are not [usually] showing up at the 7 p.m. community master plan meeting.”