California Floater Mussels Take Fish for an Epic Joyride

Ecologist Jonathan Young steered his rowboat alongside a rectangular container that was floating between two bright orange buoys. He reached under a plastic mesh covering and pulled out a large black and brown object the size of his fist that looked a lot like a clam.

“These are the underdogs of water quality,” he said. “And also, unfortunately, on their way to extinction.”

Young is part of a team that is reintroducing the California floater mussel, a native freshwater mussel, and other native plants and animals, to Mountain Lake — a tiny 2,000-year-old natural lake located on the southern edges of San Francisco’s Presidio, nestled between the Presidio Golf Course, the Lake Street neighborhood and Park Presidio Boulevard.

The mussels, which naturally filter water and clean it, are a key part of an ambitious restoration project run by the Presidio Trust, a federal agency set up by Congress to help oversee the former military base with the National Park Service.

The California floater is just one of about 300 species of native freshwater mussels in North America, approximately two-thirds of which are threatened, endangered or species of special concern. One thing that often distinguishes them from their saltwater cousins is that most species need a host fish to live off of before they develop fully. It is a fascinatingly clever survival method, but also one of the main reasons their existence is threatened now. In lakes and waterways where the fish populations have disappeared, the mussels have no way to grow in number.

Before European settlers arrived in the late 18th century, California floater mussels were likely one of several species found in Mountain Lake, where native Ohlone people would gather food. Things began to change drastically when Spain, and then Mexico, established military bases in the Presidio. The U.S. Army took over in 1848 and maintained a military presence until 1994 when the site transferred to the National Park Service.

In 1938, when the Golden Gate Bridge was completed, the military only allowed the connecting highway to go under its golf course, and over a section of Mountain Lake. So highway engineers built a tunnel next door, filling in almost half of the lake to build the access roadway from the bridge to the city.

Over the years, the water quality and ecological balance of the lake has been significantly altered by urban activities. Millions of pounds of fertilizer used on the golf course introduced an imbalance of nutrients. For decades, toxic lead and other automobile contaminants drained directly from the roadway into the lake. Most likely due to the resulting filthy water and imbalance in the habitat, the sensitive native mussels have not naturally been found in the lake for quite some time, scientists say.

It wasn’t until 2011, when the federal government ordered Caltrans to pay $13.5 million to clean up the lake, that the possibility of restoring the mussels’ home could begin in earnest. In 2013, 17,500 cubic yards of contaminated sediment — enough to fill 1,750 dump trucks — was removed from the 4-acre lake, and the Presidio Trust put together a comprehensive plan to resurrect it.

Since 2014, Mountain Lake, its surrounding wetland and coastal scrub habitats have been the site of a large-scale ecological restoration project of native plants and animals. The goals are to improve water quality, increase biodiversity and promote public awareness in San Francisco and beyond.

In addition to the California floaters, the list of reintroduced native animal species now includes Three-spined stickleback fish, Western pond turtles, Pacific chorus frogs, California red-legged frogs and the San Francisco forktail damselfly. Reintroduced native plants include Common mare’s tail, Floating pond weed, Sago pond weed and Coon’s tail.

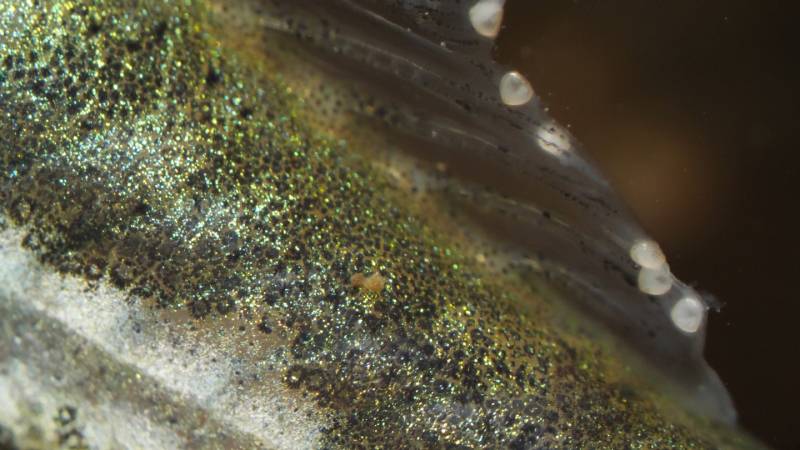

The small, sparkly three-spined stickleback fish in the lake were relocated from nearby Lobos Creek. They happen to play a critical role in the mussel’s life cycle. The mussels have evolved an ingenious method of launching their larvae, or glochidia, into the water, where they clamp onto a fish gill or fin. The larvae hitch a ride on the fish for a few weeks, absorbing nutrients from their hosts, until they are ready to drop off and begin life as a young mussel on the lake bed.

With the guidance of biologist Chris Barnhart of Missouri State University, Young and his team have developed a system to help grow the mussel population in the lake and for successfully raising juvenile mussels in the lab. The biologists borrow adult mussels for a few days at a time and bring them back to a lab where they put them in small tanks with the stickleback fish. Once enough of the stickleback carry glochidia on their gills and fins, Young puts them and the mussels back into the lake.

If they’re lucky, the larvae on the fish will make it to the juvenile stage and grow up to be hardworking living water filters.

Adult mussels can live 10 years. They can filter up to 38 gallons of water each per day. This sounds like a lot — and it is. But the juvenile mussels can filter at a much higher rate relative to their body size.

“If you were to scale them up directly, they’d be four or five times a fire hose in terms of the volume they’re putting out,” Barnhart said.

The mussels each have two openings to take in and expel water. Inside them, water passes through their gills, which are lined with thousands of cilia, tiny arms that filter out the nutrients and particles.

Thousands of mussels in a small lake or waterway can have a big effect on overall water health and clarity, Barnhart said. Also, their industrious filtration and sensitivity to pollutants makes them reliable indicators of freshwater quality. The sensitivity of mussels to ammonia led the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to cut the allowable limit for ammonia content in half, in 2013.

Mussels share their watery homes with a world-class array of freshwater fish, snails, crayfish and insects.

“When you add it all up, freshwater holds a big chunk of the biodiversity of North America,” Barnhart said. “Mussel habitat is everybody’s habitat. The fact that so many of them are endangered, sadly, is one of the best reasons to be interested in them.”

Their endangered status sets a legal reason for preserving rivers, he noted, which helps protect all life they share habitats with.

One specific goal at Mountain Lake is to establish a self-sustaining population of mussels, the researchers said. The water quality has been monitored once a month for 20 years, so Young and his team have a good idea of the health of the lake. But knowing how the reintroduced mussels are doing is a crucial next step. Barnhart said he has plans to send a graduate student from Missouri State University to do the first extensive survey of mussels in the lake since the reintroduction project began.

To get a sense of how established the mussels are, the student will dive in the lake and survey uniform square sections of the lake bed for mussels. The researcher also will look for free-swimming stickleback fish that already have the glochidia on them, showing that the fish are getting connected with the mussels in the wild. If the project is successful, Young said, it can be replicated in other watersheds in California. Not only would this introduce a native species back into other local streams and rivers, but it could improve water quality naturally.

“These animals need our help elsewhere, not just in this lake,” he said.

There are significant challenges, however. Before the reintroduction process, Young and his team worked hard to remove a majority of the fish, turtles and other non-native animals in the lake that could eat the mussels and other native animals. But invasive species like crayfish are still difficult to control.

An exploding population of crayfish on a small lake can have a disastrous effect on the fledgling population of mussels. Young estimated that the researchers have removed roughly 100 pounds of crayfish from the lake over the past six years.

Although not a problem so far in Mountain Lake, the Asian clam, quagga mussel and zebra mussel are invasive species of freshwater mussels (originating in Europe and Asia). The zebra and quagga attach to surfaces and inside pipes with sticky threads, wreaking havoc on boats, docks, water treatment plants and power plant cooling systems across the Great Lakes. The prolific Asian clam threatens to outcompete native species for precious resources in places like Lake Tahoe.

North American freshwater mussels live unattached, and also differ from the invasive species in that their life spans are much longer – some species live as long as 30 years. By contrast, zebra and quagga have one-to-three-year lifespans and don’t need a host fish to parasitize as one of their stages of development. This shortened life span and direct development enable the invasive mussels to adjust more easily to climate change and pollution.

“The complex life cycle of the native mussels just doesn’t hold up well under modern circumstances,” Barnhart said. “They need stable habitat that lasts for decades, and that is in short supply now.”

Although not commonly known, freshwater mussels have a colorful history. Most “pearl” buttons before World War II in the U.S. were made from the shells of freshwater mussels harvested in the wild. After the war, manufacturers switched to plastic buttons. Freshwater mussel shells were also used as seeds to cultivate pearls in oysters raised on commercial pearl farms in Japan.

“The shell harvest was almost like a mining industry. It’s hard to imagine how abundant these animals were,” Barnhart said. “You could not walk across rivers without stepping on them.”

The commercial harvest contributed to the decline of freshwater mussels, but it was the environmental effects of dams, industrialization and habitat loss that led more directly to extinction of many native species, Barnhart added. As of 2019, 34 species are believed to be extinct, and 91 are listed as threatened or endangered species.

Barnhart likens the ambitious Mountain Lake project to the restoration of a museum piece. It’s a complex system of native plants and animals, managed by humans in an urban environment. Completely restoring the lake to its pre-European settler state is a difficult goal, he said. But the process is an excellent opportunity and valuable learning resource for the researchers and the general public.

The project already has made huge strides in improving the water quality and native species living in the lake, but there’s still a way to go before it’s a pristine environment, the researchers say. Over the past three years, they have successfully inoculated over 1,000 stickleback fish with mussel larvae, and the harmful algae blooms in the lake have reduced significantly, but it is still unclear as to how long it will take to fully establish a self-sustaining population of mussels.

“I still wouldn’t really want to eat anything coming out of Mountain Lake,” Young said, citing the history of lead pollution and other contamination.

Ultimately, the scientists understand the complexity and imperfect nature of the work they are doing. Young said real ecosystem change at the lake could take decades.

“Right now it’s in its infancy,” Young said. “There’s always going to be ecosystem management, especially in urban areas. There is never going to be a time when you can just walk away from it.”